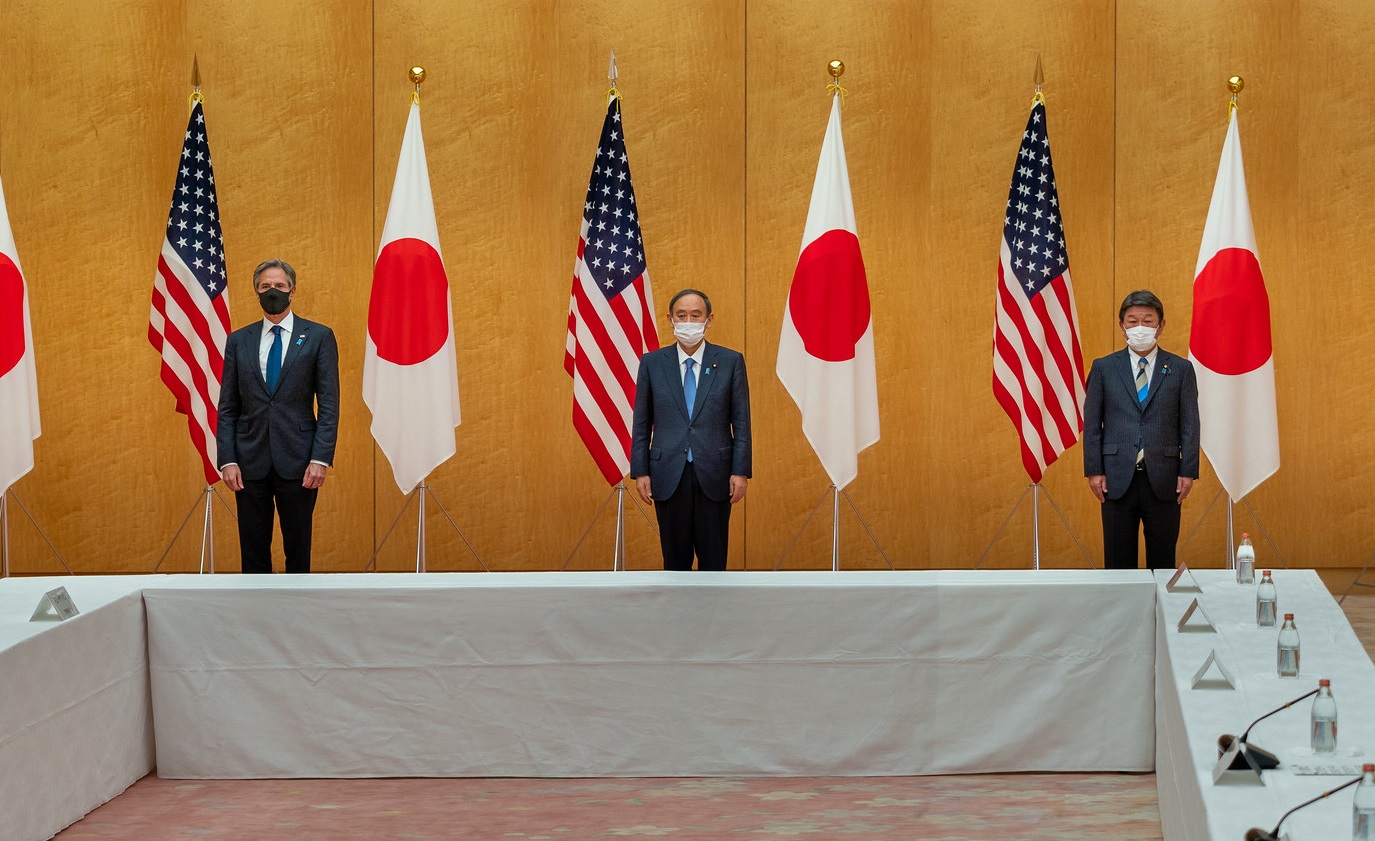

A summit between Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide and US President Joe Biden took place on April 16, and a joint statement was released. The fact that the leaders of Japan and the United States reaffirmed the importance of the security of the Taiwan Strait for the first time in 52 years since 1969 reflected their shared assessment of the deteriorating relations across the Taiwan Strait. Picture source: Suga Yoshihide, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=3522407371197958&set=pb.100002861882726.-2207520000..&type=3.

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 26

The US-Japan Joint Leaders’ Statement: Implications for Taiwan

Tetsuo Kotani

Professor, Meikai University/Senior Fellow, Japan Institute of International Affairs

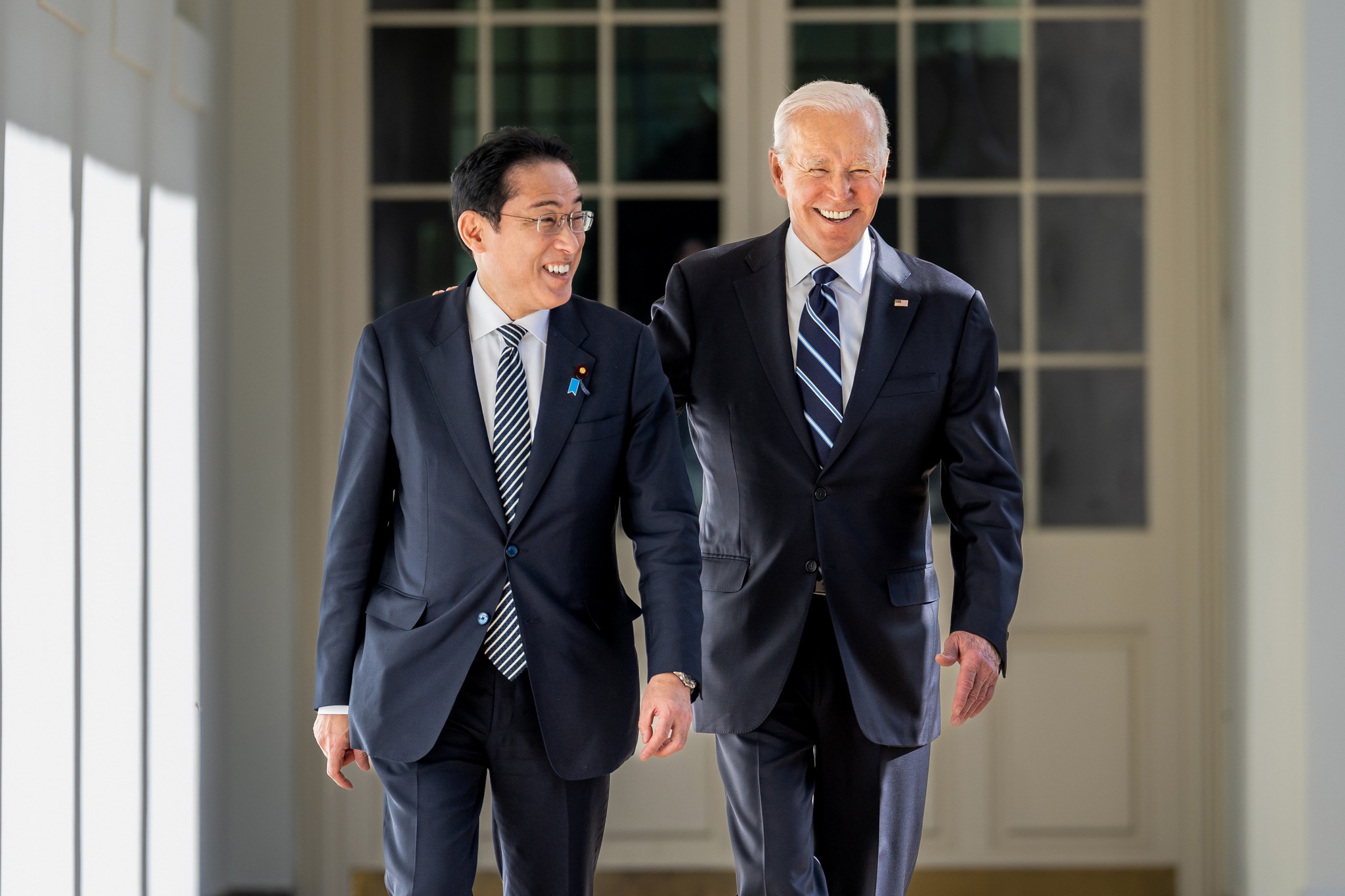

A summit between Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide and US President Joe Biden took place on April 16, and a joint statement was released. The joint statement covered a wide range of issues, but there was no doubt that China was at the forefront of all of them. The fact that the leaders of Japan and the United States reaffirmed the importance of the security of the Taiwan Strait for the first time in 52 years since 1969 reflected their shared assessment of the deteriorating relations across the Taiwan Strait. This paper discusses the implications of the joint statement for Taiwan.

Prime Minister Sato Eisaku and President Richard Nixon issued a joint statement on the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty in November 1969, describing the maintenance of peace and security in the “Taiwan area” as “extremely important” to Japan's security. This implied that in exchange for the return of Okinawa, Japan would guarantee flexible use of US bases in Japan based on Article XI of the Japan-US Security Treaty in the event of a Taiwan contingency. On the other hand, Tokyo assumed that there was no imminent threat against Taiwan, given that the military balance between the United States and China at the time was overwhelmingly in favor of the former.

However, the environment surrounding Taiwan is very different today than it was in 1969. At a Senate hearing in March, Admiral Phil Davidson, the outgoing Commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, testified that the military balance in the Western Pacific was becoming even more unfavorable to the US military, charting the People's Liberation Army's growing capabilities over the past two decades, and suggested the possibility of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan “within the next six years,” amid growing nationalism in China. Reportedly, the US military is increasingly losing ground to the People’s Liberation Army in tabletop war games, and the commander’s remarks reflects a growing sense of emergency within the US military.

In Japan, meanwhile, there is growing concern that a Taiwan contingency will become a Japan contingency. This is because of the geographical proximity between Okinawa and Taiwan, and if China were to launch an armed attack on Taiwan, US bases in Okinawa would be the first targets for Chinese precision weapons to prevent US intervention. Or, China may take the Senkaku Islands at the same time as launching an armed attack on Taiwan. Therefore, for Japan, a Taiwan contingency is no longer a fire on the opposite shore. In other words, a Taiwan contingency is an issue that should be considered based on Article V of the Japan-US Security Treaty, rather than Article XI.

Against this background, Suga and Biden referred to Taiwan in the joint statement. How should Japan contribute to the peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait?

First, Japan should contribute indirectly to the defense of Taiwan by defending itself. In the joint statement, Suga expressed his resolve to bolster Japan’s own defense capabilities, while Biden emphasized his strong commitment to the defense of Japan, using the full range of US capabilities, including nuclear. As long as Japan’s southwestern islands and US bases in Okinawa are safe, Beijing needs to think twice before waging an invasion of Taiwan. To put it another way, Japan needs to build a defensive wall over the southwestern islands by steadily developing a “Multi-Domain Joint Defense Force,” envisioned in the 2018 National Defense Program Guidelines.

At the same time to further deepen defense cooperation with the United States, the two allies should launch a joint operational planning and combined training and exercises, not only for the defense of the southwestern islands but also for a contingency in Taiwan. In addition, in order to effectively deal with the 1,200+ missiles that China possesses, both Japan and the United States need to increase their missile defense capabilities and deploy medium-range ground-based missiles on the first island chain. This will require difficult consultation with local communities in Japan, but it is an unavoidable issue to improve deterrence

Second, Japan should also consider how to cooperate with Taiwan on defense even under the one-China policy. While bilateral defense cooperation is unrealistic, there are some venues to pursue. For example, intelligence cooperation either directly with Taiwan, or indirectly through the United States, should be considered, given the operations of the PLA in the Bashi Strait is a common concern. Even if bilateral engagement is difficult, Japan and Taiwan could train together in the US-sponsored RIMPAC and other multilateral frameworks. People-to-people exchanges, which is critical for defense cooperation, should be expanded, for example, through track II platforms.

Third, in order to maintain peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait, it is necessary to shift the military balance between China and Taiwan which overwhelmingly favors China. The United States provides arms to Taiwan under the Taiwan Relations Act. The former Trump administration continued to support Taiwan’s defense efforts through the sale of drones, mines, anti-ship missiles, as well as the extension of the life of the PAC-3 interceptor missiles. The Biden administration is also expected to support Taiwan’s defense efforts. Japan, too, needs to develop its legal foundation for supporting Taiwan’s self-defense capabilities in light of the reality in which the United States and European countries are providing arms to Taiwan even under their one-China policies.

Lastly, Japan still needs to consider a Taiwan contingency under Article XI of the Security Treaty. A Chinese invasion against Taiwan-owned remote islands with no civilian population such as the Pratas Islands, might not involve an attack on Japanese soil. If the United States decides to provide support for Taiwan, then Japan would not only allow Washington to use US bases in Japan under Article XI but also provide logistical support under the US-Japan Defense Guidelines. Japan and the United States should prepare for such a scenario, as well as a full-scale invasion of Taiwan, to make sure that Beijing does not underestimate the resolve of Tokyo and Washington to preserve peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait.