Biden’s Asia Visit Sets a Baseline for U.S. Engagement with the Indo Pacific

Rhetorically, at least, President Biden’s trip to Asia made clear that the region remains a priority for this White House. The administration rolled out two meaningful and aspirational economic and security initiatives and, unintentionally or not, set new expectations for its commitment to ensure peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. Picture source: President Joe Biden, May 24, 2022, Facebook,

Biden’s Asia Visit Sets a Baseline for U.S. Engagement with the Indo Pacific

By Michael Mazza

What Happens in Europe Doesn’t Stay in Europe

If Biden’s first presidential trip to Asia had a theme, it was global interconnectedness. This White House, for example, is looking abroad for solutions to problems the United States.S. is facing at home. The president’s first stop made this outlook abundantly clear. During a visit to a Samsung semiconductor plant in Pyeongtaek that will serve as the model for a new Samsung factory in Texas, Biden pointed to supply chain disruptions brought about by COVID-19 and Russia’s war on Ukraine. “A critical component of how we’ll do that [securing critical supply chains],” the president argued, “is by working with close partners who do share our values, like the Republic of Korea, to secure more of what we need from our allies and partners and bolster our supply chain resilience.”

More broadly, as a senior administration official put it in a background press call, “the Biden administration is deepening our economic ties with the region to deliver for U.S. workers, businesses, consumers, and of course for people everywhere, including in the ROK.” Rhetorically, at least, President Biden’s “foreign policy for the middle class” was on full display during his trip to the region.

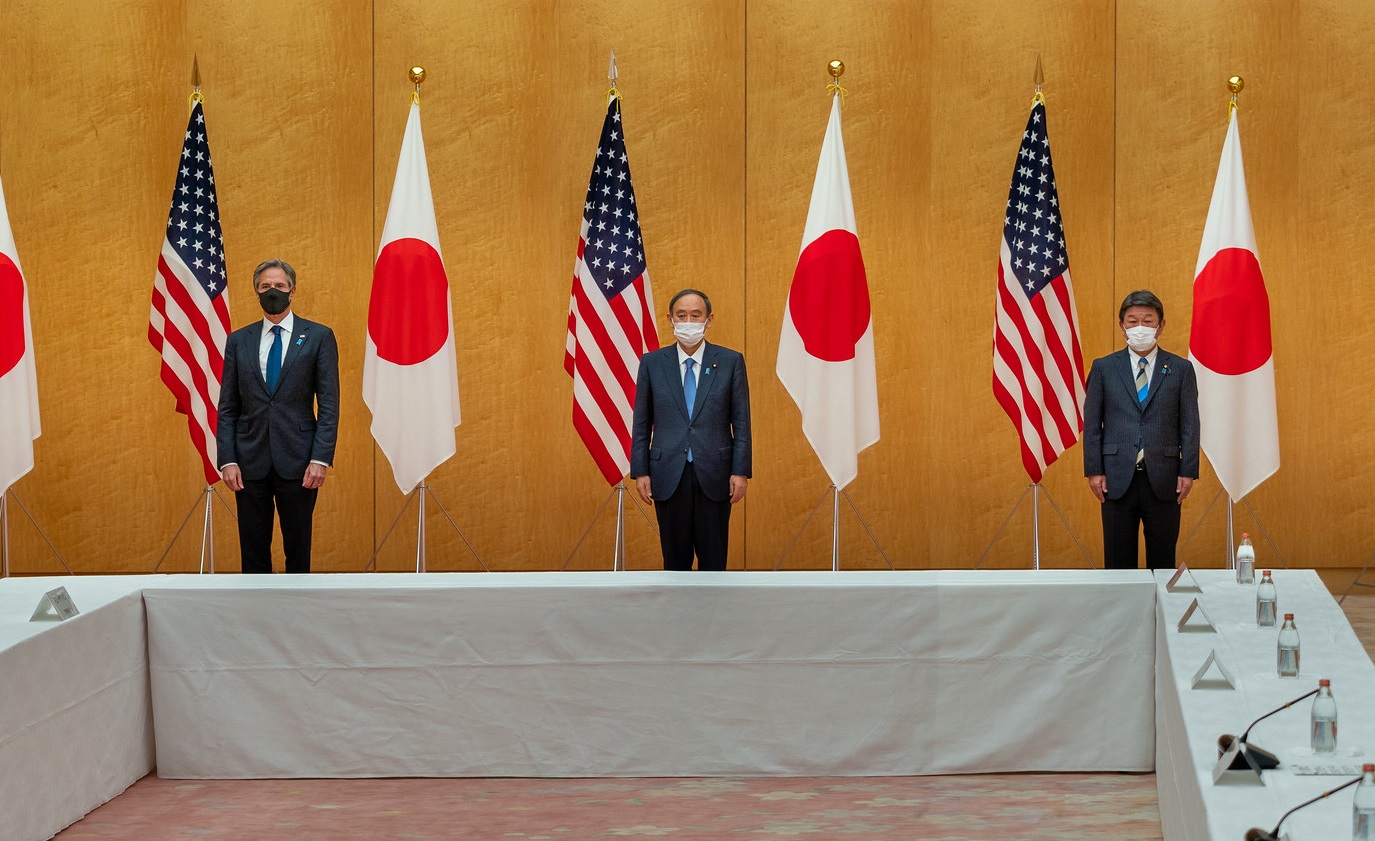

Beyond economic concerns, meanwhile, the president and his team sought to dismiss concerns that the war in Ukraine threatened to distract the United States.S. from Asia. Indeed, the president argued that challenges in Ukraine had global implications — a case with which his Indo-Pacific interlocutors appeared to agree. As the Japan-U.S. Joint Leaders’ Statement put it:

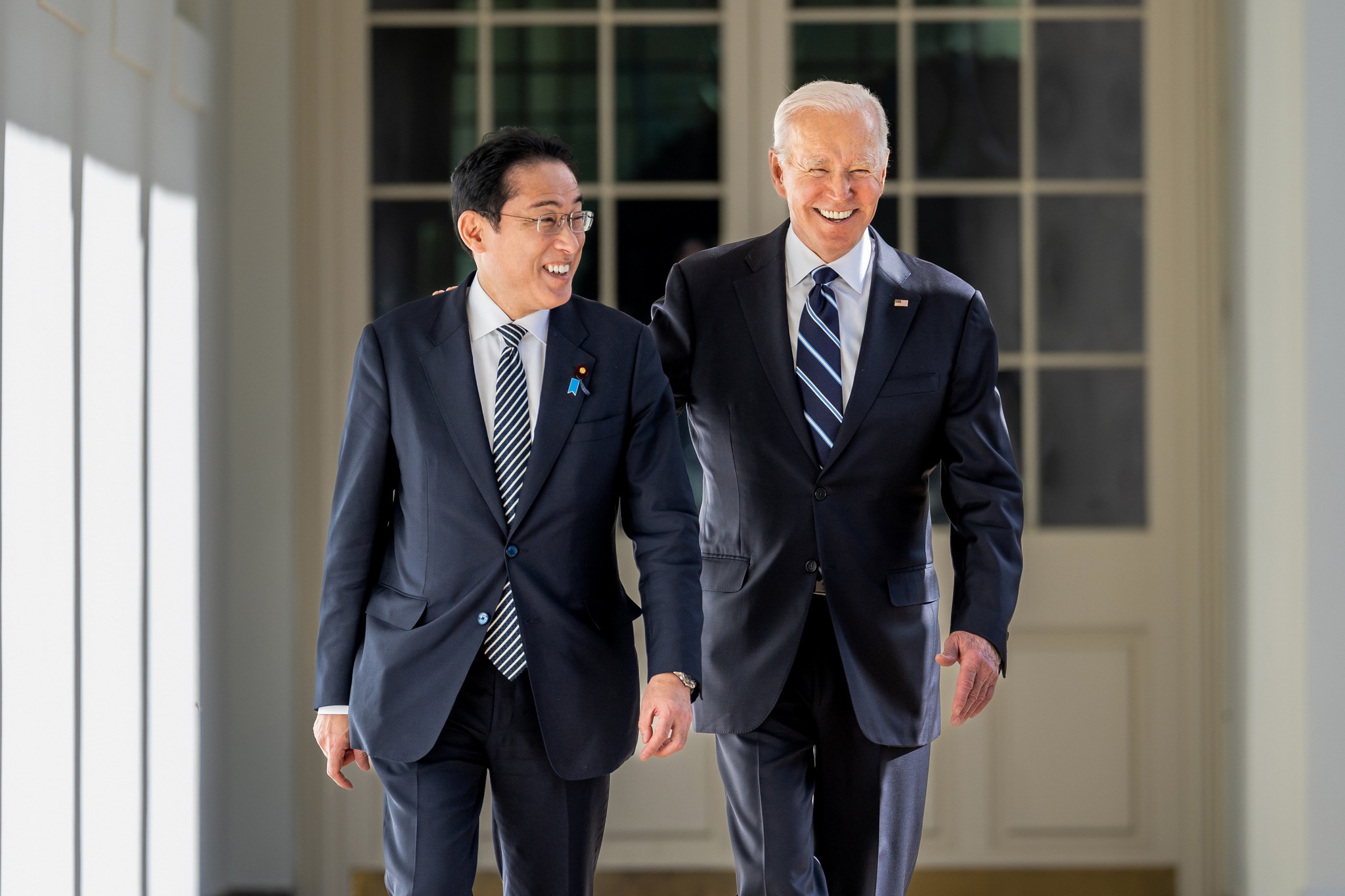

As global partners, Japan and the United States affirm that the rules-based international order is indivisible; threats to international law and the free and fair economic order anywhere constitute a challenge to our values and interests everywhere. Prime Minister Kishida and President Biden shared the view that the greatest immediate challenge to this order is Russia’s brutal, unprovoked, and unjustified aggression against Ukraine.

Regional leaders are, themselves, sticking to this message — what happens in Europe doesn’t stay in Europe — as became clear weeks later at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. Kishida, in particular, has been banging on this drum: “I myself have a strong sense of urgency that ‘Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow.’”

The “Yes” Heard Round the Word

While giving the Voldemort treatment to China — the country that shall not be named — Kishida’s concerns about “East Asia tomorrow” did not leave much room for doubt. “We must be prepared,” he told the Shangri-La Dialogue audience, “for the emergence of an entity that tramples on the peace and security of other countries by force or threat without honoring the rules.”

It is little wonder that concerns about Taiwan’s fate featured so prominently in the American president’s conversations during his trip to Asia. Indeed, Biden and his counterparts made it clear: just as Asian countries cannot ignore developments in Asia, what happens in Asia can likewise have impacts on distant shores.

In the U.S.-Japan joint statement, the American and Japanese leaders described the Indo-Pacific as “a region of vital importance to global peace, security, and prosperity” and they “reiterated the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait as an indispensable element in security and prosperity in the international community” (emphasis added). President Biden and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol similarly emphasized “the importance of preserving peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait as an essential element in security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region” (emphasis added). Even the Quad, which tends to be more reticent vis-à-vis Taiwan due to Indian sensitivities, included an oblique reference to the Taiwan Strait in its joint statement by warning against “any unilateral attempt to change the status quo.”

Put another way, Taiwan is neither a sideshow nor a Chinese internal affair as China’s leaders like to claim. Rather, without peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait, there can be no peace and stability in Asia writ large or even the wider world.

President Biden punctuated his concerns, and those of partner nations, about the risk of Chinese aggression with what may or may not have been an unintentional slip of the tongue. When asked if he is “willing to get involved militarily to defend Taiwan,” the president opted for direct language: “Yes.” Full stop. Asked to clarify, he explained, “that’s the commitment we made.” If Taiwan were to be forcefully annexed, the president went on, it would “dislocate the entire region.” In language that was a bit unclear, he seemed to say that the rationale for direct US intervention in a Taiwan crisis would be far stronger than it has been for Ukraine, where the United States has committed significant treasure but no blood.

This marked the third time in his presidency that Biden indicated he would defend Taiwan. And for a third time, administration officials quickly walked back those comments. As I have argued elsewhere: “regardless of stated policy, by this point it seems clear the president is personally committed to defending Taiwan against a Chinese attack.”

Setting a Baseline

Although the president’s Taiwan comments may have created some discomfort for the other leaders with whom he was meeting — they now faced closer scrutiny of their own approaches to Taiwan — the comments may also have been welcomed. For example, Shinzo Abe, the still influential former Japanese prime minister, argued in April that “the time has come for the US to make clear that it will defend Taiwan against any attempted Chinese invasion.” Despite President Biden’s later insistence that “the policy has not changed at all,” regional expectations now may have shifted. Pacific partners will judge the Biden administration, in part, on whether it intensifies its efforts to secure Taiwan during the next two years.

A proper assessment of the Biden administration’s Asia policy will also depend on its performance in building on two major initiatives rolled out during the president’s recent trip. Two years into its term of office, the Biden administration finally sought to address a problem in America’s Asia policy that has existed since day one of the Trump presidency: the lack of any positive economic agenda for the region. The answer — the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) — is uninspiring, largely because it does not meet a regional demand for liberalized trade arrangements, nor will it secure greater market access in Asia for American exporters.

Even so, IPEF is ambitious. American National Security Adviseor Jake Sullivan described it thusly:

IPEF is a 21st century economic arrangement designed to tackle 21st century economic challenges, ranging from setting the rules of the road for the digital economy, to ensuring secure and resilient supply chains, to helping make the kinds of major investments necessary in clean energy infrastructure and the clean energy transition, to raising standards for transparency, fair taxation, and anti-corruption.

How and whether the administration can deliver on IPEF’s potential is an open question. Indeed, there appears to be little urgency to do so. According to the IPEF joint statement, the parties have agreed only to “launch collective discussions toward future negotiations.” On IPEF, the Biden administration will have to spend the next two years earning the self-congratulations it has been so quick to offer up.

Finally, countries across the region likely welcome the Quad’s announcement of the new Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA). With many in the region unable to effectively monitor their own waters, let alone those waters beyond territorial limits, IPMDA will meet a pressing need. In building a common operating picture (COP) of the region stretching from the Indian Ocean, through Southeast Asia, and out to the Pacific Islands, IPMDA “will allow tracking of ‘dark shipping’ and other tactical-level activities, such as rendezvous at sea, as well as improve partners’ ability to respond to climate and humanitarian events and to protect their fisheries, which are vital to many Indo-Pacific economies.”

The Biden administration, hopefully alongside Quad partners, should be ready to help countries across the region act on the new information to which they will now have access. If Pacific Island nations, for example, become newly aware of illegal fishing in their waters, but do not have the capacity to enforce their territorial rights, then there will be further opportunities for Washington and others to provide meaningful assistance and, in so doing, deepen ties. On the other hand, there is a danger that the Biden administration will leave the job half-done.

The IPMDA will rely on commercially-available data to build its COP, meaning that it will be unclassified and allow for broad regional participation. Hopefully the Biden administration and its Quad partners are considering this just a first step in building a comprehensive COP — one that, ultimately, will not rely solely on commercial data. Patterns of cooperation within the IPMDA may create space and opportunity for the sharing of classified MDA among select partners, with even greater security implications or the Indo-Pacific.

Conclusion

Rhetorically, at least, President Biden’s trip to Asia made clear that the region remains a priority for this White House. The administration rolled out two meaningful and aspirational economic and security initiatives and, unintentionally or not, set new expectations for its commitment to ensure peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. Can Washington dedicate the needed time and resources to follow-through while grappling with war in Europe, domestic economic challenges, and a fractured and polarized electorate at home? Only time will tell.

(Michael Mazza is a nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, the Global Taiwan Institute, and the German Marshall Fund of the United States.)