Navigating US-China Rivalry in International Trade: Middle Powers and the CPTPP

If Ukraine’s situation offers any lessons to the CPTPP community, the desire to avoid difficult decisions through delays does not make them disappear, and the failure to shield a vulnerable neighbor can have dire consequences for all. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Navigating US-China Rivalry in International Trade: Middle Powers and the CPTPP

Prospects & Perspectives No. 49

By Meredith B. Lilly

Introduction

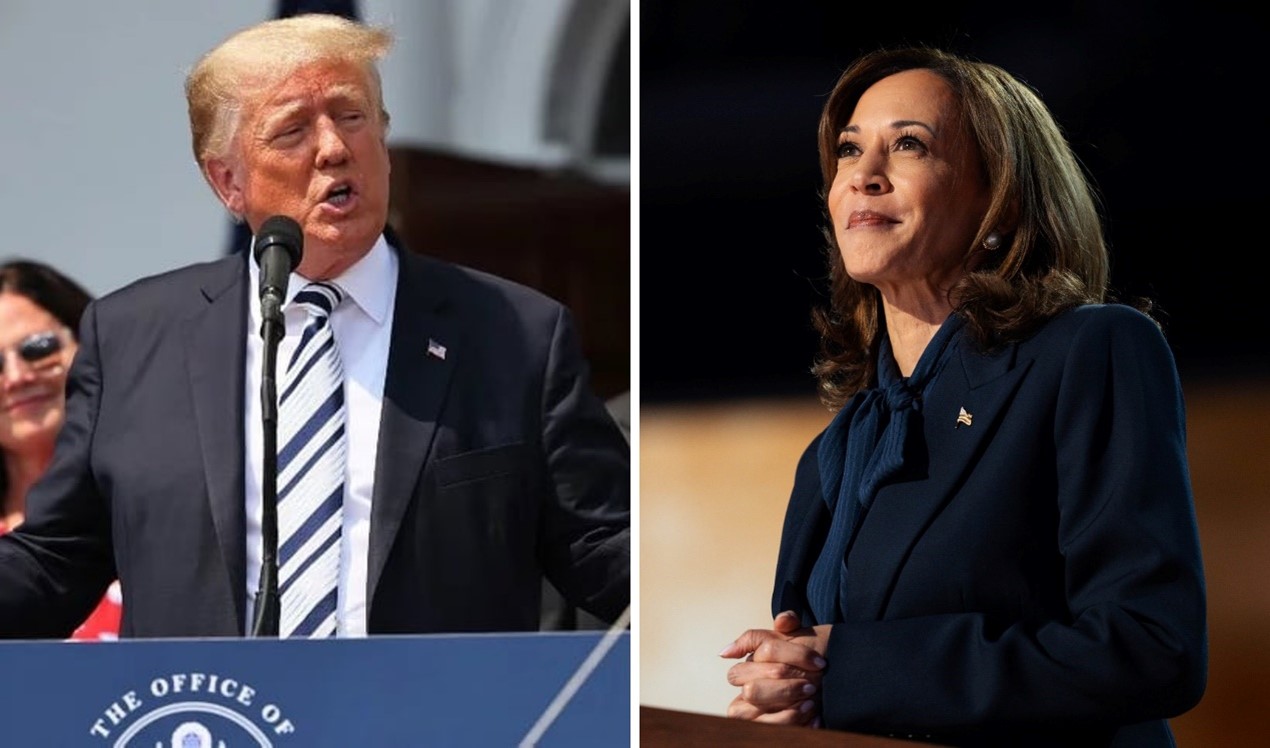

Over 18 months since Trump left office, tensions between the United States and China have continued under the Biden Administration. China has engaged in increasingly aggressive foreign policy in the lead up to the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Congress later this year, when leader Xi Jinping will try to secure an unprecedented third term. Meanwhile, the U.S. has launched its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which Beijing has interpreted as an attempt to lure regional countries away from China’s orbit and more firmly into the U.S.’ sphere of influence. The 13 countries handpicked by the U.S. for engagement in its strategy represent both high-growth advanced economies such as South Korea and Japan, alongside populous emerging markets such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia.

While these countries welcome greater U.S. engagement in the region, most do not want to be placed in the position of having to take sides in the U.S.–China rivalry. Countries seeking to advance their relationship with the U.S. via the new IPEF are also working hard to clarify their own goals for regional trade initiatives that are open to all countries, including China.

Canada offers one example of a country that has experienced both successes and disappointments as it has sought to navigate this rivalry. As its only territorial neighbor, the U.S. is Canada’s largest trading partner and closest ally. Yet Canada has also been subject to the negative consequences of American exceptionalism. U.S. administrations of both stripes have on occasion used American unilateralism to disadvantage Canada’s trade interests. Some of these continue under the Biden administration, including protectionist measures under the banner of Made in America policies. Despite these setbacks, Canada and the U.S. continue to address their disagreements productively, while simultaneously focusing on areas of agreement and cooperation. These are the markers of a mature bilateral relationship.

Meanwhile, Canada has just endured a very difficult period of tension with China over the illegal imprisonment of two Canadian citizens, Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig. Their detentions were made in retaliation for Canada’s upholding of its extradition treaty with the U.S. after Canadian authorities arrested Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou. China’s hostage diplomacy had a severe impact on bilateral relations, both in real economic and policy terms and has also severely impacted Canadian public opinion toward China. Thus, having been thrust into the middle of the U.S.–China rivalry, Canada continues to learn lessons about steering through these difficult waters.

While Canada’s relationship to the U.S. is a primordial one, charting its future course with China remains uncertain. Nevertheless, Canada has important trade and bilateral interests with China, and it is essential that Canada develop a strategy for moving forward in the region despite tensions. One way Canada can successfully manage these challenges is via trade, and its approach to enlarging the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Specifically, Canada and other CPTPP member countries can demonstrate how middle powers can work constructively to apply international rules in a manner that allows them to make progress on trade liberalization without allowing U.S.–China rivalry to define the future of this trade agreement. By applying a rules-based process, all prospective applicants — including Taiwan — can be considered based on the merits of their economic and trade policies and the potential benefits they can bring to the trade agreement.

Growing the CPTPP

CPTPP is an 11-country agreement that was designed with a flexible structure, open to any new members who sought to reach the agreement’s high standards and ambition. While the U.S.’ withdrawal was as a major blow at the time, in the face of U.S.-China rivalry, the absence of both countries currently serves as an opportunity to address the trade interests of other regional economies without the domination of either power. Yet, even without the U.S. and China in the CPTPP, both remain highly influential to CPTPP members and the process of accession. For example, while China represents the largest single trade partner of most CPTPP member countries, the U.S. is the largest bilateral trade partner of Mexico and Canada, and a defence ally to Japan and Australia. As the largest three economies in the CPTPP, Japan, Canada, and Australia can cooperate to wield considerable influence over the accession process. Meanwhile, three of eleven current CPTPP members have not yet ratified the agreement (Brunei, Chile and Malaysia), meaning they do not fully benefit from its provisions or make decisions about the accession of new members.

In 2021, the United Kingdom was the first to trigger the accession process for new membership, and is the only country currently approved to negotiate entry. Since then, five other countries have applied to join or indicated their intention to do so: China, Taiwan, Ecuador, Costa Rica and South Korea. From a GDP rankings perspective, China, Taiwan and South Korea can offer strong economic value, while Ecuador and Costa Rica can help strengthen CPTPP’s regional footprint in the Americas. In addition — other countries that may consider joining in future, such as Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines, also represent major and important economies of the region.

Rules, Not Exceptions, Should Drive the Accession Process

Though many are concerned about how to manage both Taiwan and China’s applications simultaneously, this should be a very clear process. China will strongly object to Taiwan’s membership and will undertake extraordinary efforts to pressure CPTPP members to reject Taiwan’s application. However, Taiwan is a WTO member and therefore, its application should be given full consideration.

Despite not being a CPTPP member, the U.S. will also attempt to exert influence to ensure China’s rejection from the pact, through its IPEF negotiations and by applying leverage in its bilateral relationships with member countries. With Canada and Mexico especially, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s (USMCA) Non-Market economy clause will certainly be invoked if necessary.

Yet, it is these expectations of exceptional treatment by both the U.S. and China which underscore the imperative to focus on the agreement’s high standards and ambition to guide consideration of new members, rather than political and economic influence. Instead of bowing to such pressure, Canada and other CPTPP members should focus on the provisions of the agreement and welcome any countries who can demonstrate adherence to them through reforms implemented prior to accession. Such a rules-bound process will favor open economies such as Taiwan and South Korea, while disadvantaging a closed economy such as China, which would need to undertake considerable structural reforms before it could be permitted to accede. In this way, the CPTPP process can offer an example of the manner in which members can work constructively to apply rules, standards and trade evidence to evaluate potential entrants, while downplaying expectations for influence by powerful non-member countries.

Conclusion

Until very recently, many countries have studiously sought to avoid provoking China by ignoring its threats to Taiwan. Ukraine’s experience with Russia demonstrates the dangers of such timidity. The CPTPP accession process is in danger of suffering from similar avoidance strategies with respect to China. If Ukraine’s situation offers any lessons to the CPTPP community, the desire to avoid difficult decisions through delays does not make them disappear, and the failure to shield a vulnerable neighbor can have dire consequences for all. CPTPP members have an opportunity to lead this effort to set aside politically motivated challenges to Taiwan’s accession, and consider its case on trade and economic grounds. It is important for states that are committed to the rules-based order to keep moving forward, and not to allow the rivalry to either the U.S. or China paralyze progress on multilateral initiatives.

(Dr. Meredith B. Lilly is Associate Professor, Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University.)