The Need for Coalition-Building to Counter the PRC’s Grey Zone Activities in the South China Sea

By resorting to an array of “grey zone” tactics, Beijing aims to progressively eat away at the status quo in the South China Sea while staying under the threshold of crisis. If China succeeds in dominating the South China Sea, it is likely to dominate Southeast Asia at large, as well as gaining strategic leverage over the major maritime economies of Northeast Asia: Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Picture source: Philippines Coast Guard, August 12, 2023, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_Militia#/media/File:PRC_maritime_militia_ship_00001.jpg.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 51

The Need for Coalition-Building to Counter the PRC’s Grey Zone Activities in the South China Sea

By Euan Graham

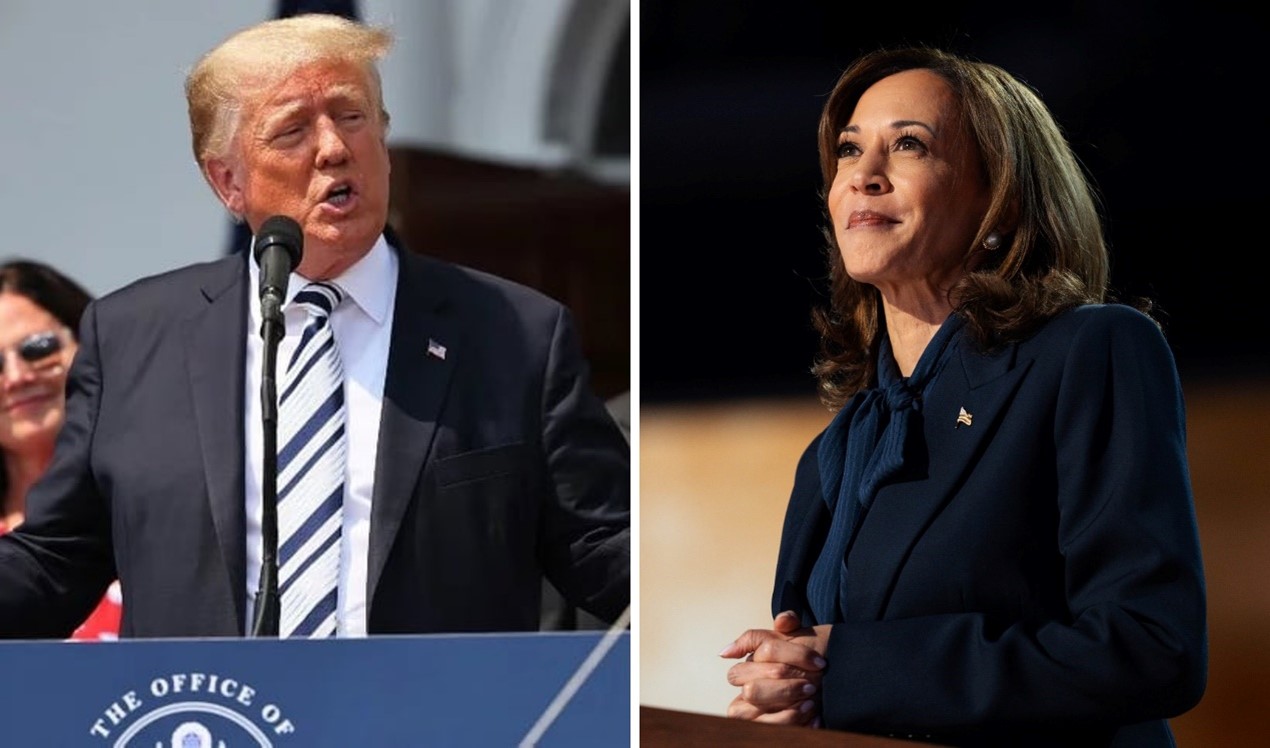

By resorting to an array of “grey zone” tactics, Beijing aims to progressively eat away at the status quo in the South China Sea while staying under the threshold of crisis. By insidiously enforcing its maritime claims and pushing out its presence, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) further aims to inculcate a defeatist, compliant mindset among rival territorial claimants in the South China Sea and Southeast Asian states more generally. If China succeeds in dominating the South China Sea, it is likely to dominate Southeast Asia at large, as well as gaining strategic leverage over the major maritime economies of Northeast Asia: Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

Through the skillful coordinated use of assets from the PRC’s maritime militia, the China Coast Guard and the People’s Liberation Army, grey zone tactics have already enabled Beijing to exert effective control over large tracts of the South China Sea. Grey zone operations extend into the information domain, where the PRC relentlessly platforms its claims and attempts to delegitimize those of its rivals, as well as the security interests of non-littoral states in the South China Sea including the United States, its Indo-Pacific allies and partners, and European countries.

All is not lost

As gloomy as the strategic situation appears, the South China Sea is not completely lost yet. The Philippines, which has lately borne the brunt of China’s coercion, has refused to bow under intense pressure. Manila has also received significant international support and solidarity, despite encountering ambivalence from some of its fellow members of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Vietnam, which occupies the largest number of features in the Spratly Islands and has a large exclusive economic zone, has also managed to hold on.

Furthermore, international law including UNCLOS overwhelmingly supports the maritime jurisdiction of Southeast Asian littoral states over China’s ambiguous and baseless ambit claim in the South China Sea. This is reflected in widespread international support for the Philippines legal victory over China in the Permanent Court of Arbitrations ad hoc tribunal judgment of 2016, including from non-aligned countries such as India.

But this remains some distance short of an organized coalition to counter the PRC’s grey zone activities in the South China Sea.

Coalition-building

The core of such a coalition must be the Southeast Asian claimants themselves. They must recognize that the concerted threat they face from the PRC requires them to settle or at least to shelve their internecine maritime disputes. Vietnam and the Philippines have made some progress in this regard, as has Indonesia despite its official position that it has no direct boundary dispute with the PRC. Vietnam has shown public solidarity with the Philippines, despite its confrontational stance towards China under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.. Malaysia is the outlier among ASEAN territorial claimants, preferring to deal with Beijing bilaterally and sometimes adopting diplomatic positions that have matched China’s demands to exclude the United States and others from involvement in the South China Sea. Among the non-claimant ASEAN states, Singapore needs to rediscover its voice as an impartial advocate of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea. And whenever China’s grey-zone behaviour towards the Philippines, or others, clearly contravenes the 2002 ASEAN-China Declaration of Conduct, Singapore and other ASEAN members should not shy from saying so publicly, and in the ongoing Code of Conduct negotiations between ASEAN and China, interminable though these seemingly are.

A role for Taiwan

Taiwan also has an important role to play, as both claimant and occupier of the largest natural feature within the Spratly Islands. Taipei has a direct interest in not allowing the PRC’s grey-zone activities near Second Thomas and Sabina shoals to normalize blockade tactics that could be scaled up in future against Taiwan itself or its outlying islands. Taiwan has also acquired deep experience of the PRC’s maritime activities in its immediate vicinity. Sharing such information with Southeast Asian “frontline” states in the South China Sea would be helpful for them to develop their own grey-zone counter-measures.

Taiwan has shown some interest in emulating the example set by the Philippines Coast Guard, in “naming and shaming” China’s gray zone activities. Transparency campaigns can be useful for generating international support and staking out the moral high ground against the PRC. But they are very limited in terms of moderating Beijing’s behavior, as Manila has found out arguably to its cost. Transparency is not tenable as a stand-alone strategy against an adversary like the PRC, which is impervious to reputational damage. To be effective, transparency needs to be integrated into a national maritime strategy, with support from the armed forces and a centrally coordinated government communications approach.

International partners

International partners should certainly call out China by name when condemning its grey zone behavior in the South China Sea. Currently, there are not enough statements of solidarity with the Philippines and too often these are delegated down to the ambassadors in Manila, when foreign minister statements would carry more authority. Non-littoral countries, especially major maritime states, should clearly articulate that their national interests are at stake in the SCS. Recent Japanese statements in support of the Philippines have been good in this regard, as have those of the EU. South Korea needs to be much more vocal, given its potential vulnerability to the disruption of shipping through the South China Sea.

Statements of solidarity (“standing with”, etc.) should lead to supportive actions if they are to be meaningful. Articulating national interests in the South China Sea creates a logic for governments to move beyond declarations of solidarity to providing material support, in the form of capacity building to boost Southeast Asian states’ maritime domain awareness, or gifting vessels and aircraft to assert presence and deny the PRC space to occupy the grey zone.

Governments need to be beware of bad-faith offers of dialogue on maritime issues from Beijing, which mask efforts to neuter public criticism of the PRC by appearing to offer a closed-door forum to air concerns and privately influence China’s thinking. Once established, the maintenance of such sham dialogues is made contingent on the subjective health of bilateral relations — a slippery slope to self-censorship.

Finally, acceptance of the grey-zone paradigm should not prevent escalatory reactions when these are appropriate. When China’s provocations in the South China Sea, East China Sea, Taiwan Strait or elsewhere cross the line from grey zone to black and white; for example, military intrusions into uncontested territorial airspace and waters, then governments need to be step up their reactions accordingly.

(Euan Graham is a Senior Analyst, Australian Strategic Policy Institute.)