Team Biden in Tokyo and Seoul: A Good Start for an Ambitious Project

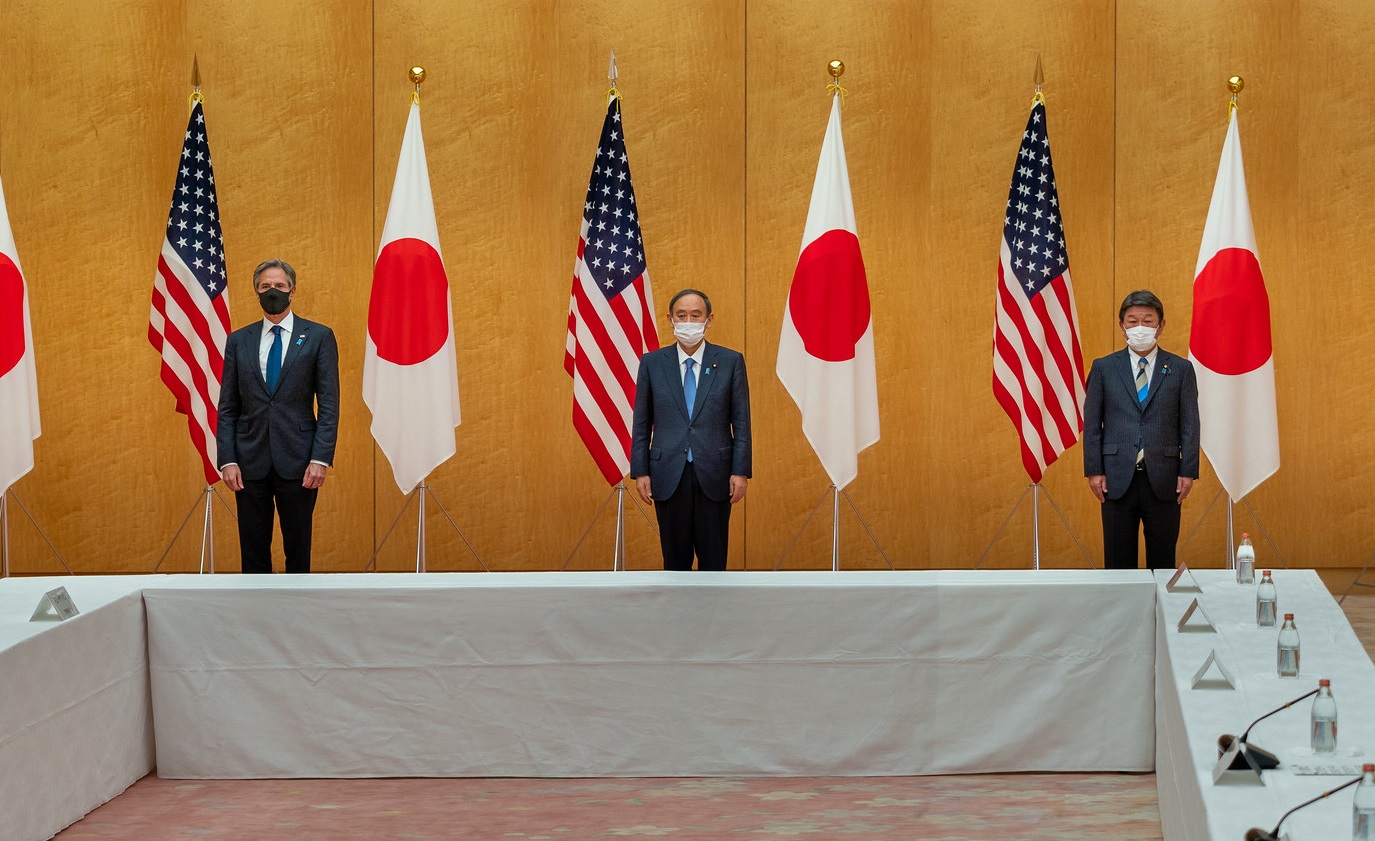

Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin traveled to Tokyo and Seoul last month in what was the administration’s first Cabinet-level (and in-person) interactions with its allies. Per a Pentagon release, the meetings aimed to bolster both alliances “in the face of long-term competition with China.” Picture source: U.S. Department of State, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/statephotos/51042240018/.

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 19

Team Biden in Tokyo and Seoul: A Good Start for an Ambitious Project

David Santoro

Vice President and Director for Nuclear Policy, Pacific Forum

April 21, 2021

Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin traveled to Tokyo and Seoul last month in what was the administration’s first Cabinet-level (and in-person) interactions with its allies. Per a Pentagon release, the meetings aimed to bolster both alliances “in the face of long-term competition with China.”

This is an easier sell in Tokyo than in Seoul, and it is even harder to bring about trilateral security cooperation. Nonetheless, Team Biden’s debut act in Asia got off on the right foot.

The meetings did not happen in a vacuum. They occurred following President Biden’s virtual summit with the leaders of Australia, India, and Japan, which form the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or “Quad”—an informal dialogue between the four countries held in part to improve coordination in the face of China’s increasing assertive posture—and before Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan held the administration’s first meeting with Chinese officials in Anchorage, during which time Austin visited India to discuss future cooperation and “promote a free and open regional order.”

This “allies-first” approach is consistent with Biden’s promise to “build a united front of allies and partners to confront China.” It contrasts with the previous administration, which was confrontational towards China but often towards some U.S. allies as well, even as its National Security Strategy and other key strategy documents stressed their importance.

The Backdrop

The administration’s good performance in Tokyo and Seoul was built on several prior actions. Before and after taking office in January, Biden spoke to the Japanese and South Korean leaders. He reaffirmed the U.S. commitment to both alliances, including, in Japan’s case, to the Senkaku Islands’ defense, a priority for Tokyo.

His team also concluded deals with both countries on host-nation support: an extension of the current arrangement with Japan, with ongoing negotiations expected to result in a larger Japanese contribution, and a new agreement with South Korea, which includes a 13-percent increase for Seoul. The deals removed important irritants in both relationships, as the previous administration wanted major spending hikes from allies, fivefold in South Korea’s case-which was a nonstarter.

Moreover, before the Tokyo and Seoul meetings, the Biden administration released the “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance”. The Guidance calls China “the only competitor potentially capable of…[mounting] a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system” and states that the United States will respond by renewing its strength and working “in common cause with [its] closest allies and partners.”

The Pentagon will help in this effort through its “Global Posture Review,” which will update the U.S. military’s footprint, resources, and strategies.

Resounding Success in Tokyo

The United States deems Japan an essential ally because U.S. strategists would struggle to respond to a crisis in Asia without the U.S. military presence on Japanese soil its largest overseas deployment. In a recent Congressional hearing, Admiral Philip Davidson, the outgoing commander of the Indo-Pacific Command, explained that it takes three weeks to address a contingency in the first island chain from the U.S. West Coast, and seventeen days from Alaska. Forward-deployed forces in Japan fill that gap.

That’s why Davidson stated that “the Japanese are…critically important to the security of the region.” That’s also why the statement of the Blinken/Austin meeting with their Japanese counterparts, Foreign Affairs Minister Toshimitsu Motegi and Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi, noted the United States’ “unwavering commitment to the defense of Japan” and labelled the U.S.-Japan Alliance “the cornerstone of peace, security, and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific.”

Japanese are comfortable with this language because they value their alliance with the United States and have their own strategy for the “Indo-Pacific,” a concept they coined, initially by referring to “broader Asia”. That strategy, which they have aligned with U.S. regional goals, seeks to check China geopolitically by deepening coordination with their closest partners and developing new partnerships.

Unsurprisingly, then, the Japanese and Americans were in sync about the “China problem” in Tokyo. It was even the primary focus. The meeting statement includes criticisms of Chinese “destabilizing” actions in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, the East and South China Seas, and even Taiwan (a first), and offers in response an endorsement of the “free and open Indo-Pacific,” “rules-based international order,” and Quad as key elements of a peaceful and secure regional order, in addition to a commitment to maintaining “the Alliance’s operational readiness and deterrent posture.”

In contrast, the statement from the last meeting in 2019 solely “expressed serious concern about, and strong opposition to, unilateral coercive attempts to alter the status quo in the East China Sea (ECS) and South China Sea (SCS).”

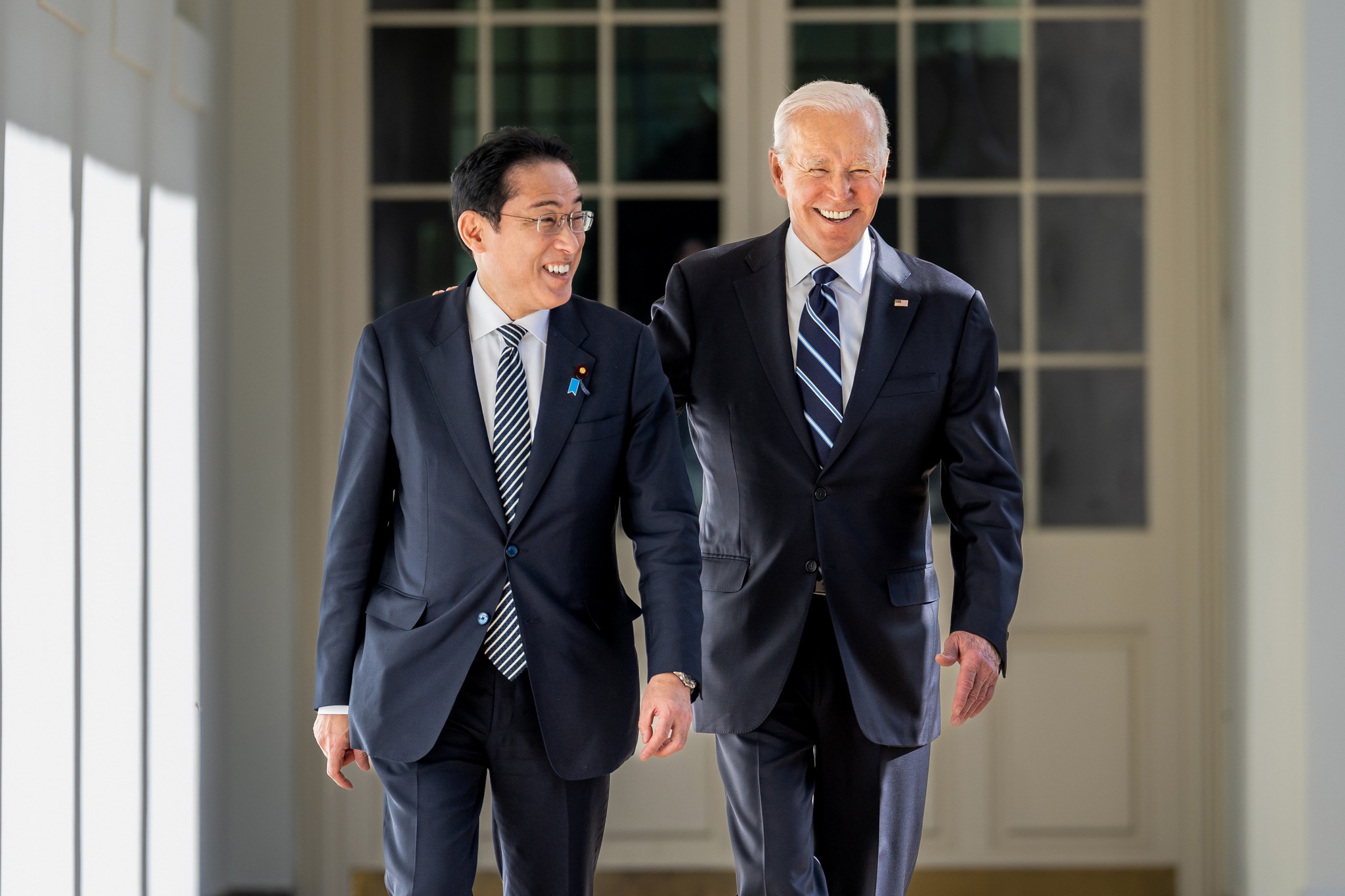

Of course, questions remain, notably Japan’s willingness to increase defense spending sufficiently. Still, on all counts, the Tokyo meeting was a resounding success, and the future looks bright for U.S.-Japan relations, with Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga being the first foreign leader to be hosted at the White House on April 16.

Positive Notes in Seoul, but Challenges Abound

The Seoul meeting, too, was positive. Blinken, Austin, and their South Korean counterparts Foreign Affairs Minister Chung Eui-yong and National Defense Minister Suh Wook agreed that the U.S.-South Korea Alliance “has never been more important,” stressing that it is “the linchpin of peace, security, and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula and the Indo-Pacific region.”

Both sides reaffirmed their commitments under the Mutual Defense Treaty and vowed to strengthen the “Alliance deterrence posture” and maintain “joint readiness.” They stressed that the Alliance’s priority was to combat North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons and missiles, and the United States confirmed that its policy review towards that country would be conducted in consultation with South Korea. Both sides also promised closer cooperation on other issues.

The Seoul meeting statement, however, does not mention China. When the U.S. side voiced criticisms of Chinese actions during the talks, the South Korean side remained silent. Both sides agreed to protect a “free and open Indo-Pacific” and “rules-based international order,” but South Koreans avoided expressing support for the Quad and instead talked about South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s more innocent “New Southern Policy,” a signal that Seoul, unlike Tokyo, does not want to take sides in the U.S.-China rivalry. One reason is Seoul’s economic dependency on China; another its hope to resolve the Korean conflict, which requires U.S. and Chinese cooperation.

Still, the Seoul meeting was successful because it helped put the Alliance back on track after years of turmoil under the previous U.S. administration. South Koreans, however, made clear that they are not prepared to back the United States (or Japan) to challenge China. The focus of the U.S.-South Korea Alliance, plainly, will remain the Peninsula, and there too, issues will persist: there is still no resolution on the process of transferring operational control of the Combined Forces Command from the United States to South Korea, for instance.

Trilateral Security Cooperation: An Aspirational Goal

In both Tokyo and Seoul, the U.S. side also made a push for trilateral U.S.-Japan-South Korea security cooperation, which it linked to the Quad as an essential piece of the Indo-Pacific architecture to confront China. The Tokyo and Seoul meeting statements include language about the importance of such cooperation, but the prospects are dim because Japan-South Korea relations are dire and improvement is unlikely to happen any time soon.

That said, the United States appears determined to try and advance trilateral cooperation, with Sullivan hosting a discussion with his Japanese and South Korean counterparts, Kitamura Shigeru and Suh Hoon, after the Tokyo and Seoul meetings. Perhaps trilateral cooperation can thrive in select areas, such as deterrence of North Korea, which, as some have argued, should be a priority.

The Biden administration’s debut act in Asia was solid but showed that building a united front to take on China will be no easy task. Tokyo seems onboard. Seoul, however, has other priorities.