After the G7 and NATO Summits: Multilateralism and the Biden Administration

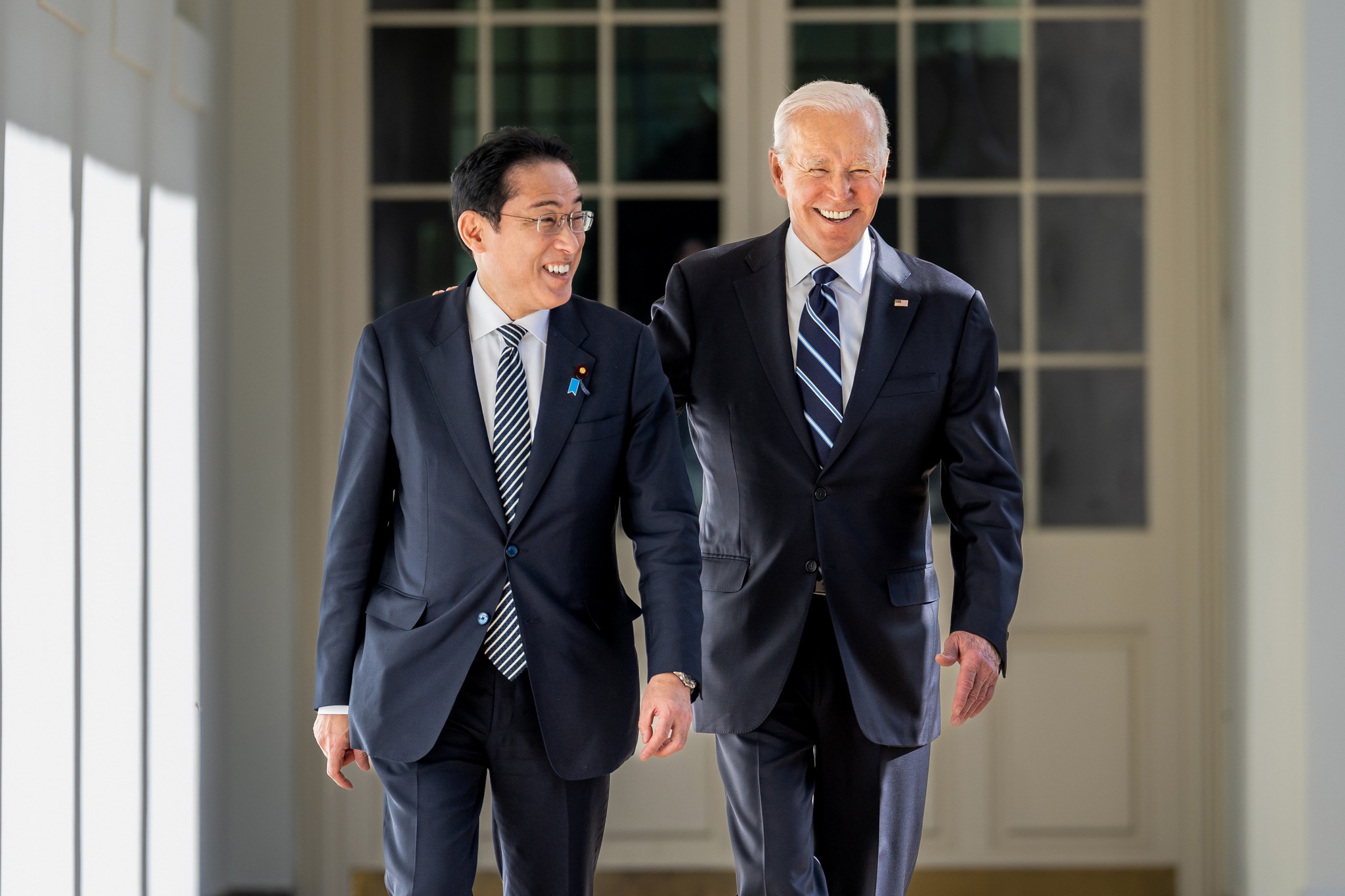

While some member states, such as Germany, have counseled greater focus on the collaborative aspects of the G7’s relationship with revisionist states, the U.S. side has taken a firmer line on democracy and human rights, as underscored by the emphasis on Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Picture Source: President Joe Biden, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/POTUS/photos/a.107570957986108/244291417647394/.

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 30

After the G7 and NATO Summits: Multilateralism and the Biden Administration

J. Michael Cole

Senior Fellow, Global Taiwan Institute,

Senior Fellow, Macdonald-Laurier Institute,

Senior Fellow, Taiwan Studies Programme, University of Nottingham

June 18 2021

Two back-to-back summits in early June 2021, the Group of Seven meeting held in Cornwall, U.K., on June 11-13, and that of the North Atlantic Council, held in Brussels, Belgium, on June 14, have resulted in landmark communiqués that signal a new commitment to multilateralism in an age of resurgent authoritarian pressure. The forceful statements of intent, which in some areas encountered occasional reluctance by a handful of member states, were largely the result of U.S. President Joe Biden’s proactive stance on the issues of our time following a spotty track record of American support for multilateralism under his predecessor.

Issued with the addition of the leaders of Australia, India, the Republic of Korea, and South Africa, the Carbis Bay G7 Summit Communiqué’s “Shared Agenda for Global Action” stipulates that vision and that the ambitions it contains are not limited to a leadership role for a small club of powerful states; instead, it goes out of its way to underscore the necessity of enlarging this club by collaborating with other multilateral institutions, including the G20 Summit, COP26, CBD15, as well as the U.N. General Assembly—the latter being a particularly challenging area, given the substantial influence that China has accumulated there over the past decade, especially among developing states.

The statement also emphasizes that members will “advance this open agenda … within the multilateral rules-based system,” language which no doubt takes aim at revisionist states, such as China and Russia, whose behavior as they become more assertive has often violated international rules or reinterpreted them in a manner that does not reflect their original intent. (The terms “rules-based system” or “order” appear on four occasions in the statement.)

The agenda proposed in the wake of the G7 summit is a very ambitious one, touching on a number of issues, such as global health, global economic recovery, free and fair trade, future frontiers (e.g., cyberspace), climate and the environment, gender equality, and global responsibility and international action (including the strengthening of the G7 Rapid Response Mechanism to counter foreign threats to democracy). Both China and Russia have been singled out in terms of calls by the G7 upon those states to act in predictable fashion and to ensure peace and stability in their respective peripheries. Although some areas, such as trade, cyberspace, and the environment, will require cooperation with states like China and Russia, the statement does not shy away from the group’s commitment to challenge autocratic countries on respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. While some member states, such as Germany, have counseled greater focus on the collaborative aspects of the G7’s relationship with revisionist states, the U.S. side has taken a firmer line on democracy and human rights, as underscored by the emphasis on Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The approach, therefore, seems to be similar to that taken by the West during its ideological confrontation with the USSR: collaboration where possible, but no concessions—at least in the communiqué’s aspirations—on human rights and democracy. Such an approach should ensure that countries like China and Russia will be less in a position where they can dilute the West’s commitment to human rights and democracy for the sake of collaboration on other issues.

The Brussels Summit Communiqué, issued in the name of the heads of state and government of the 30 North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies, reaffirms the indispensability of the transatlantic alliance to the security of its member states. Despite NATO’s main focus on traditional security challenges, including terrorism (mentioned 18 times) and Russia (62 times), the Communiqué explicitly mentions Chinese behavior as a new source of security threats to member states (China is mentioned 10 times in the statement). “China’s stated ambitions and assertive behaviour,” it says, “present systemic challenges to the rules-based international order and to areas relevant to Alliance security. We are concerned by those coercive policies which stand in contrast to the fundamental values enshrined in the Washington Treaty.” (The statement makes six references to a rules-based international order.) It continues: “It is opaque in implementing its military modernisation and its publicly declared military-civil fusion strategy. It is also cooperating militarily with Russia, including through participation in Russian exercises in the Euro-Atlantic area. We remain concerned with China’s frequent lack of transparency and use of disinformation.” Much as with the G7 statement, the Brussels Communiqué nevertheless expresses a wish to collaborate with China where collaboration is possible. NATO maintains a constructive dialogue with China where possible. “Based on our interests, we welcome opportunities to engage with China on areas of relevance to the Alliance and on common challenges such as climate change.”

While the objectives set in the G7 and Brussels communiqués are impressive and welcome from the standpoint of the necessity of tightening a multilateral response to 21st century threats, success in many areas will be contingent on member states’ willingness to make the appropriate investments. As the latter states, “Delivering on the NATO 2030 agenda, the three core tasks and the next Strategic Concept requires adequate resourcing through national defense expenditure and common funding.” Defense expenditure has long been an issue within the transatlantic alliance, resulting in criticism by both the Trump administration and that of his predecessors, who insisted that member states must be willing to invest more in their national defense. Convincing those states to do more will be one of the greatest challenges facing the Biden administration and will be key to the success of the U.S.-led multilateral order. Much of this will depend on Washington’s ability to persuade, as well as on other member states’ recognition of the nature and scope of the threats, traditional and nontraditional, facing them.