For the very first time in U.S.-Korea partnership,they emphasized “the importance of preserving peace and stability in the TaiwanStrait.” Picture Source: President Joe Biden, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/POTUS/photos/224127986330404/

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 31

The Biden-Moon Summit:

ByYeh-chung Lu

June 18 2021

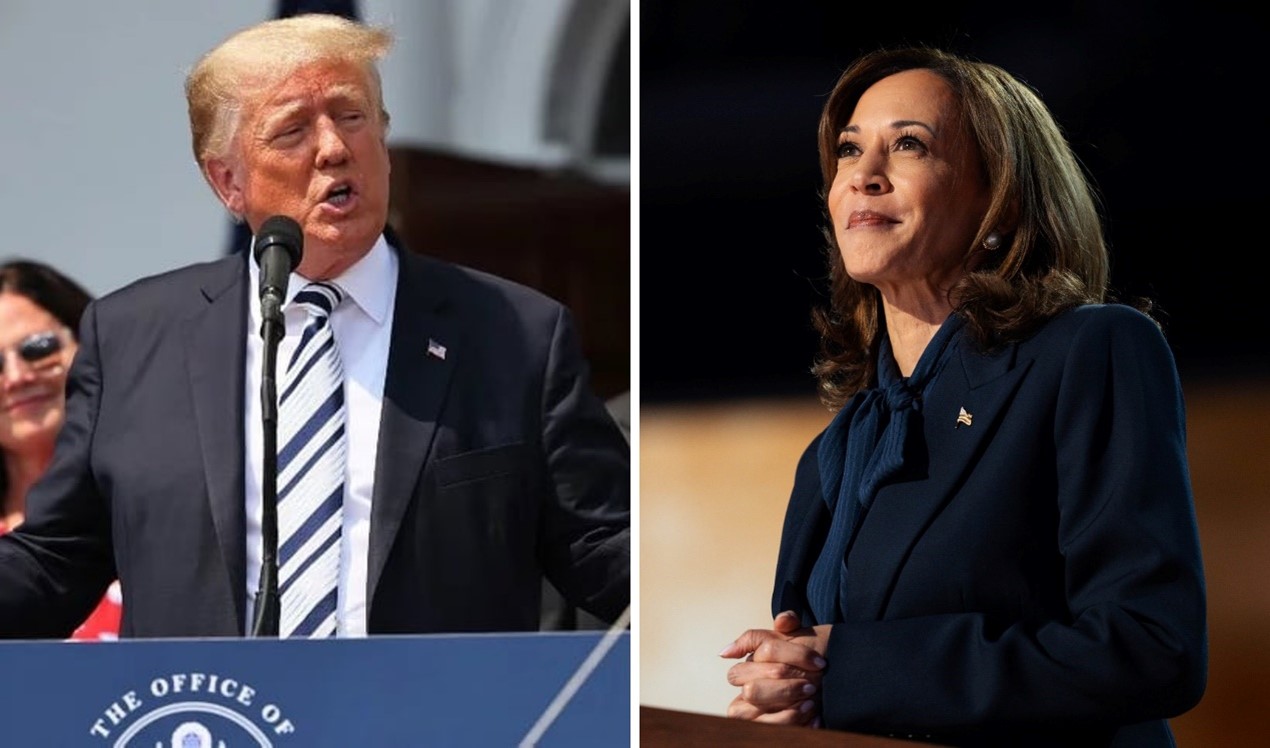

U.S.President Joe Biden received President Moon Jae-in of South Korea at the WhiteHouse on May 21, 2021. The summit is symbolic, as this was the first time forthe two gentlemen to meet after Biden’s inauguration in January as part ofBiden’s plan to realize the goal of regaining U.S. credibility and leadershiparound the world. For Moon, the not-so-chummy bromance between him and Trumpworried South Korea, and this summit served as a great opportunity to reaffirmbilateral ties with the U.S. and to boost his own popularity at home in theless-than-one-year tenure in presidency.

U.S.-Korea Alliance for aNew Chapter

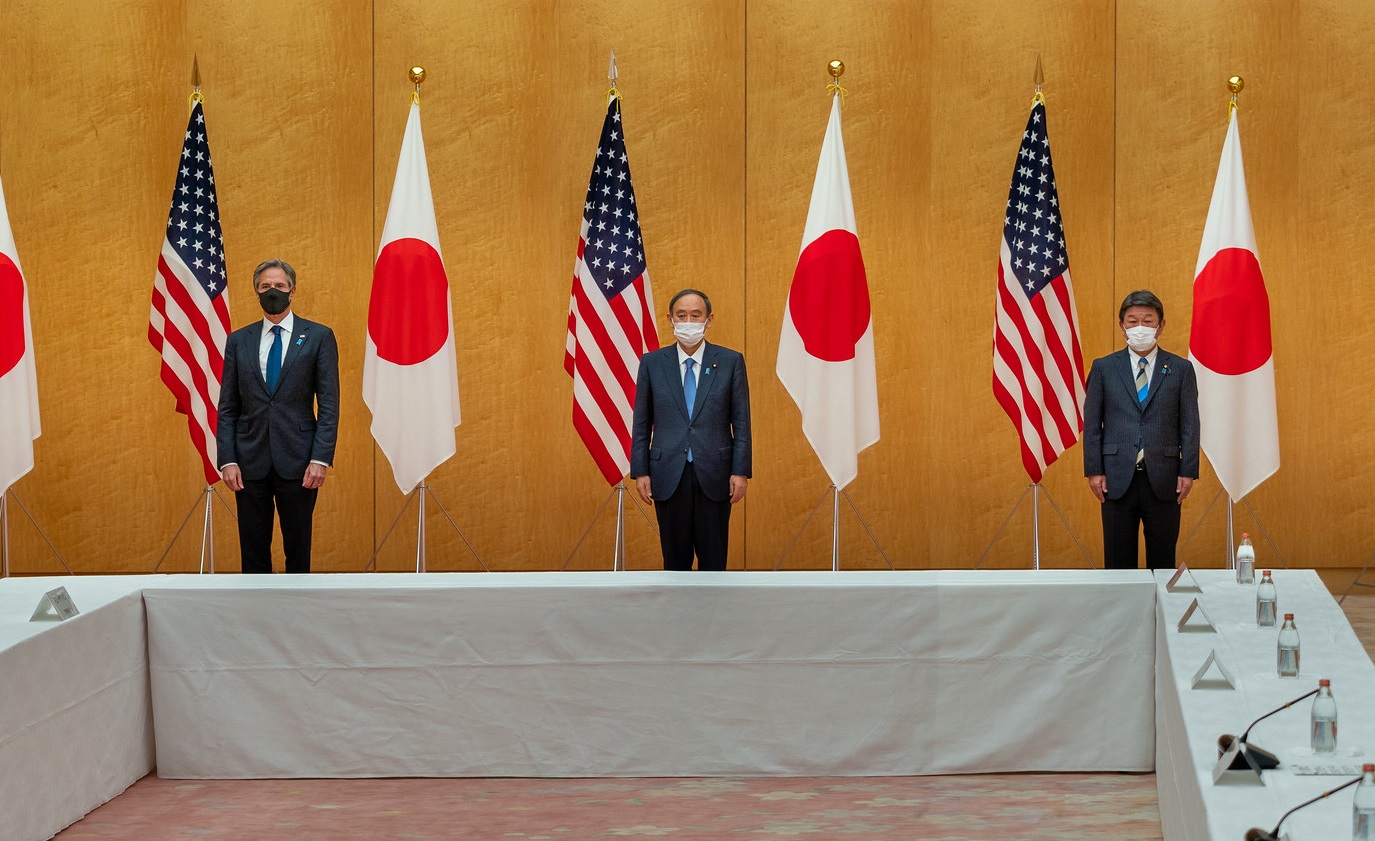

President Bidenseems to have a clear goal in mind and a blueprint in carrying out his foreignpolicy. In March, he participated in the virtual meeting of the Quad and sentout two Secretaries for field trips into the Indo-Pacific Region. Afterconsultations with close allies, Biden’s top diplomats conversed in Alaska withtheir counterparts from the serious competition to America (China). Not only isthe sequence deserving of our attention, the substance is even moresignificant. Taking these meetings together, the overarching issues includecoping with Covid-19, climate change, strengthening the global supply chain ofsemiconductors, and promoting values and democracy.

In the jointstatement, Biden and Moon reaffirmed this partnership is “a linchpin for theregional and global order” and shared the “vision for a region governed bydemocratic norms, human rights, and the rule of law at home and abroad.”Denuclearization with the means of both dialogues and sanctions remains acommon goal of the two allies. In addition, by not calling out names, the twopresidents agreed to “oppose all activities that undermine, destabilize, orthreaten the rules-based international order and commit to maintaining aninclusive, free, and open Indo-Pacific.” Also, for the very first time in theU.S.-Korea partnership, they emphasized “the importance of preserving peace andstability in the Taiwan Strait.”

In their exchanges,Biden agreed to terminate the revised missile guidelines originally signed in1979 to cap South Korea’s missile capabilities, marking progress for the Moonadministration in regaining “missile sovereignty” and being more independentfrom U.S. control over national defense. Biden also announced the appointmentof Ambassador Sung Kim, a well-seasoned diplomat with a North Korean portfolio,as special envoy on North Korea. Moon consented to cooperate with the Quad,ASEAN, and the U.S.-Japan-Korea trilateral mechanism, on issues ranging fromvaccine supplies, digital transformation, and climate change, to Burma and theSouth China Sea.

The China Factor

China weighsheavy in Biden’s blueprint for diplomacy, and the competition is ready to stayfor years to come. When Japan’s Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide visited Biden inApril, both sides explicitly deemed China’s disruptive behaviors as“inconsistent with the international rules-based order,” and emphasized “theimportance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait and encourage thepeaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues” in the leaders’ statement. The term“China” appeared in this document seven times, including the contexts of theEast and South China Seas.

In comparison,with only one mention of “China” while pledging “freedom of navigation andoverflight in the South China Sea and beyond,” the statement between Biden andMoon intentionally toned down the menace China put forth in the Indo-Pacificregion. The statement also forewent the reference to “the peaceful resolutionof cross-Strait issues.” Although the target of concern is obvious, what we seeis South Korea’s adoption of an implicit, pointing “You-Know-Who,” instead ofnames strategy on the China factor. In Moon’s visit to Congress, he voiced that“the development of U.S.-China relations is also important to South Korea,” andthat Seoul will help “maintain the stability of U.S.-China ties on the basis ofthe South Korea-U.S. alliance.” Apparently, South Korea aims to hold a balancedposition between its largest trading partner and its most important securityally.

Unsurprisingly,China reacted to the Biden-Moon statement on May 24 with complaints against theU.S. intention in expression, but more specifically on the comment focused onTaiwan (meddling China’s “internal affairs”), calling it “playing with fire.”On May 25, nevertheless, China exerted its economic influence by stating thatSouth Korean enterprises are welcome to play an important role in strengtheningbilateral economic and trade cooperation. In response, South Korean ForeignMinister Chung Eui-yong expressed South Korea has “refrained from makingspecific comments about China’s internal affairs,” and Seoul’s one-China policyremains unabated, adding that “the joint statement is not targeted at anyspecific country.”

The Road Ahead

It is no doubtthe U.S.-ROK alliance is turning a new page, and the U.S. leadership is back.However, the China challenge is real and no longer an elephant in the room. TheQuad is in place, with the U.S.-Japan alliance playing an essential role.Nevertheless, whether South Korea would firmly stand by the allies or becomethe weakest link in the Indo-Pacific remains in question.

The first issuethat might hamper South Korea’s efforts allying with the U.S. is North Korea.It is tempting for Moon to leave his legacy of engaging North Korea as anout-going president, which for now seems to be partly in line with the Bidenadministration’s NK policy review. Of course, Moon’s relatively low approvalrating at home may prevent him from pushing his engagement policy further.However, if North Korea returns to missile and nuclear weaponry tests, it woulddefinitely complicate the U.S.-ROK alliance and the U.S.-Japan-Korea trilateralcoordination.

How theU.S.-China competition plays out is the other element that would shape SouthKorea’s choice. When we witness South Korea’s tiptoeing between the U.S. (andthe Quad) and China, it is evident that striking a delicate balance more andmore is a difficult task for any government in South Korea. China’s truculentbehaviors that challenge the rule-based international order are responsible forcreating this dilemma to neighboring countries, not only South Korea. Thatsaid, South Korea should play a more proactive role in the U.S. blueprint ofstrengthening the global semiconductor supply chain. Only by shaping thegeo-economical and geo-political components in the Indo-Pacific simultaneouslyas a joint effort, would China realize it should change its behavior for itsown good.

(Dr. Lu is Professor, Department of Diplomacy, National Cheng-chi University)