Biden in Asia: Breathing New Life Into Washington’s Asia Policy

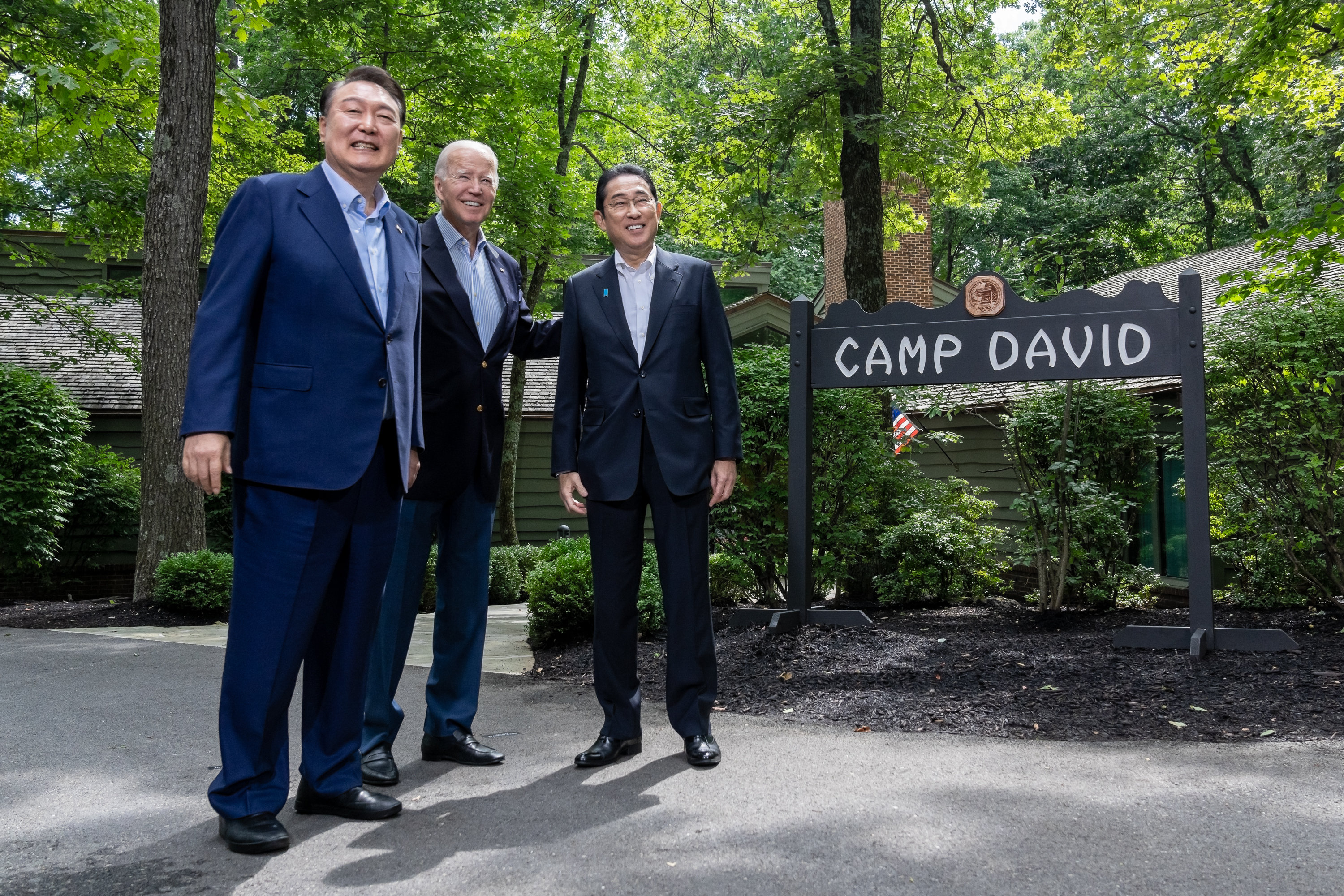

After nine months of necessary but overriding focus on the war in Ukraine, U.S. President Joe Biden traveled to Asia in November for back-to-back summits in a bid to breathe fresh life into his administration’s Asia policy.

Picture source: President Biden, November 15, 2022, Twitter, https://twitter.com/POTUS/status/1592285560990638080/photo/1.

Biden in Asia: Breathing New Life Into Washington’s Asia Policy

Prospects & Perspectives No. 71 December 1, 2022

By Michael Mazza

After nine months of necessary but overriding focus on the war in Ukraine, U.S. President Joe Biden traveled to Asia in November for back-to-back summits in a bid to breathe fresh life into his administration’s Asia policy. Only weeks earlier, in the newly released National Security Strategy, the president asserted that “the Indo-Pacific fuels much of the world’s economic growth and will be the epicenter of 21st century geopolitics … [T]he United States has a vital interest in realizing a region that is open, interconnected, prosperous, secure, and resilient.” But allies and adversaries alike have had reasons to doubt the U.S.’ commitment to pursuing that outcome. Beyond significant but narrowly focused efforts to restrain Chinese power — restrictions on technology exports, for example — the United States was arguably failing to implement (and sell) an attractive alternative vision for a region at growing risk of Chinese domination.

That risk comes not just from a rapidly modernizing People’s Liberation Army — China now has the world’s largest navy and Asia’s largest air force — but from ambitious Chinese economic statecraft. As of 2018, with the lone exception of Nepal, China was a larger trade partner than the United States for every country in the Indo-Pacific. That was true of all five U.S. allies in the region — Australia, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, and South Korea — as well as up-and-coming U.S. partners like India, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Meanwhile, China is running circles around the United States in the realm of infrastructure investment—the need for which averages US$1.7 trillion annually in Asia out to 2030. China may not be the preferred economic partner across the region, but Beijing has eagerly stepped up to the plate over the last decade; the United States, meanwhile, has barely stepped foot in the on-deck circle.

With his visits to Cambodia and Indonesia, President Biden aimed to convince Indo-Pacific countries that the United States was getting off the sidelines. In this regard, there were two notable announcements. First, while in Phnom Penh, Biden and leaders of the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations announced the elevation of bilateral U.S.-ASEAN relations to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.” Per the White House’s fact sheet, the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership will systematize high-level diplomatic engagement, support efforts to develop intra-regional connectivity, work towards sustainable development goals, find new ways to advance economic cooperation, and expand maritime cooperation. Biden also announced US$825 million in requested new spending on assistance for Southeast Asia in 2023.

In Bali several days later, Biden, Indonesian President Joko Widodo, and European Commission President Urusla von der Leyen “reaffirmed our shared commitment to strengthening global partnerships for high-standard investments in sustainable, transparent, and quality infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries.” That shared commitment comes under the aegis of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), which G7 leaders announced at their June summit. Although PGII projects are not limited to Asia, involving Indonesia — not just as an aid recipient country (which it is), but as a leader in the effort — could be a worthwhile move. As Widodo explained, “Indonesia will ensure developing countries benefit from this transformational global initiative, by working closely with partners, including in ASEAN and the Indo-Pacific region.” In short, Asia’s third-largest country by population will have a seat at the table of a global G7 initiative; together with Japan, Indonesia’s presence will ensure that the Indo-Pacific remains a priority even as developments elsewhere draw G7 attention.

When it comes to the effectiveness of development and infrastructure aid and investment, of course, the proof will be in the pudding. Whether the United States will deliver promised sums, whether it can move quickly from ideas to implementation, and whether it can begin to dilute Chinese influence as it deepens its own — these are all open questions. Still, the United States (and its partners) are clearly responding to a demand signal in the region, and that response is welcome in Asia.

Unfortunately, there are also demand signals that the United States is ignoring primarily demands for expanded trade with the United States. But the Biden administration has little interest in providing greater access to the American market for Indo-Pacific exporters, nor in securing such access in Asia for American manufacturers and service providers. Washington attempted to paper over this glaring weakness in Asia policy back in May when the president and twelve of his Indo-Pacific counterparts launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, supposedly designed to “promote fair and resilient trade,” as U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai put it. The president’s recent trip to Asia came almost exactly six months after IPEF’s inauguration. His stay-over in Indonesia, an IPEF member, provided a perfect opportunity to announce one or more major advances in the initiative. It is perhaps telling that there was nothing to announce. Many Asian leaders were likely disappointed, though not surprised, that Biden barely paid lip service to trade on his swing through the region. Indeed, as U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan put it back in May, “the fact that this is not a traditional free trade agreement is a feature of IPEF, not a bug.”

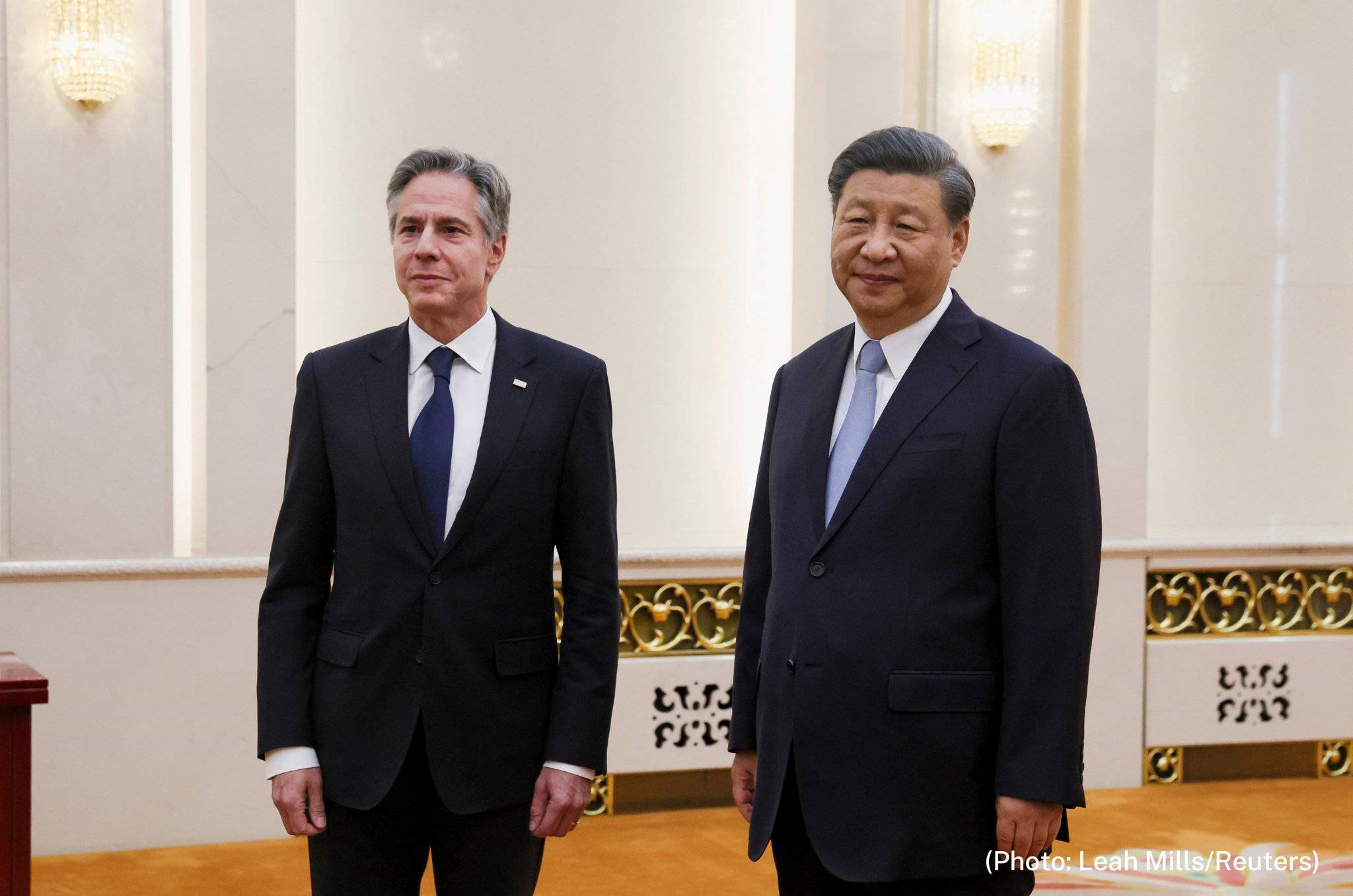

For some Asian leaders, disappointment in the United States’ years-long lack of any discernible trade agenda for the region may have been tempered by relief at Biden’s first in-person meeting as president with Chinese General Secretary Xi Jinping. As an unnamed U.S. official told reporters before the meeting, “the president believes it is critical to build a floor for the relationship and ensure that there are rules of the road that bound our competition.” Only time will tell if Biden and Xi were successful in building that floor — and, if so, how sturdy it is — but open lines of communication between the two leaders may add some ballast to the relationship in ways that introduce greater stability in the Indo-Pacific.

On the other hand, Biden and Xi did not appear to find any common ground on those issues driving their two countries apart — including human rights concerns, Taiwan, and economic competition. The fundamentals of the U.S.-China relationship quite clearly remain the same post-summit as they were pre-summit. Whether Biden and Xi, in finally meeting, bridled a stallion or simply put lipstick on a pig remains to be seen.

If competition continues to intensify, failed economic statecraft may loom larger than any American successes in diversifying regional force posture or deepening security cooperation with emerging partners. The president’s apparent priorities on his recent trip to Asia suggest an emerging appreciation of that reality. If it turns out that he laid the foundation for a more prosperous region — one largely led and underwritten by the United States — then Biden and his successors will look back on his November 2022 Asian itinerary as a great success.

(Mike Mazza is a Nonresident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the Global Taiwan Institute.)