South Korea’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report and Its Regional Implications

In December 2022 the South Korean government unveiled its first-ever Indo-Pacific Strategy report Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region. The report has attracted international attention, not only because it is the first Indo-Pacific strategy released as a publication by a country in the region, but also because of the policy positions and views it contains. Picture source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea, December 28, 2022, https://www.mofa.go.kr/viewer/skin/doc.html?fn=20221228052441348.jpg&rs=/viewer/result/202302.

South Korea’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report and Its Regional Implications

Prospects & Perspectives No. 7

By Tsun-yen Wang

In December 2022 the South Korean government unveiled its first-ever Indo-Pacific Strategy report Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region. The report has attracted international attention, not only because it is the first Indo-Pacific strategy released as a publication by a country in the region, but also because of the policy positions and views it contains. The latter is especially noteworthy, as some of the positions and viewpoints converge with those of South Korea’s allies and like-minded partners, while others may possibly be interpreted as disagreement between them.

As the report’s title indicates, South Korea champions freedom, peace and prosperity of the region, and affirms the significance of universal values shared by liberal democracies. The report also underscores South Korea’s will to “build a regional order based on norms and rules” (p. 23), to which equal importance is also attached. The report’s support for universal values and rules and norms reflects South Korea’s moral position over the global turbulence caused by authoritarian regimes, telling the world that Seoul shares the commanding heights of morality and will closely cooperate with the United States and Japan (p. 23) on such matters.

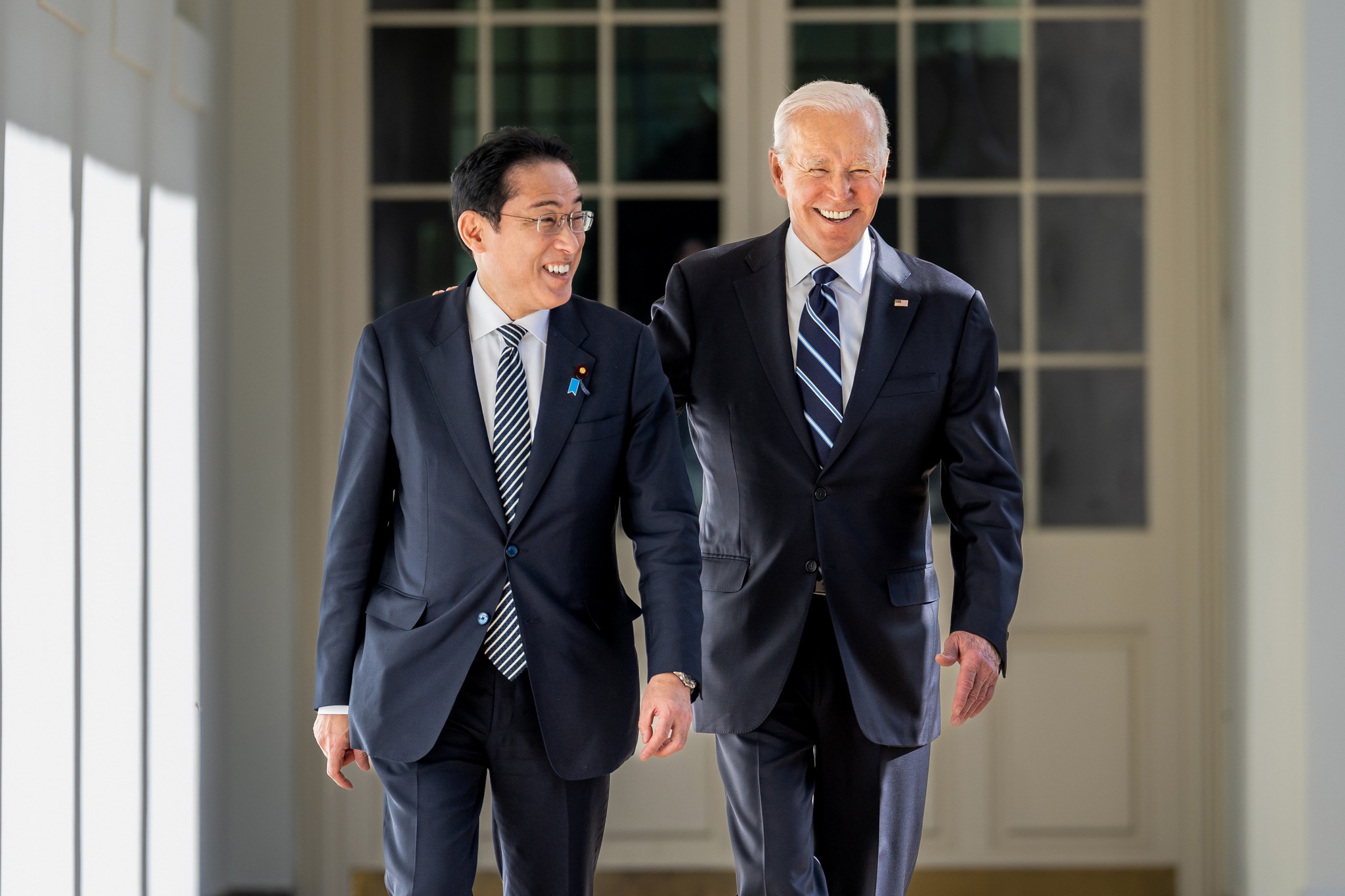

In addition to values, security is another highlight of the report. The report indicates South Korea’s emphasis on the trilateral ROK-U.S.-Japan cooperation and enhancing defense posture on such security issues as non-proliferation and terrorism (p. 26). Its mention of Taiwan — “We also reaffirm the importance of peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait for the peace and stability of the Korean Peninsula and for the security and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific” (p. 28) — is generally welcomed by the Taiwanese government. It is also a rare (if not the first) official statement of the linkage between the security of Taiwan and the Korea Peninsula by the South Korean government.

The report also stresses economic prosperity. It advocates establishing an economic security network to support open and free trade and to ensure a “stable and resilient supply chain” (p. 31). Considering the ever-worsening disruptions in world trade and manufacturing, South Korea’s commitment to a renewed push for economic development along with regional countries like Japan and Taiwan is a welcome move.

The report’s stress on values, security and prosperity reflects a consensus between South Korea and Western democracies. It is all the more remarkable when values and peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific have been under constant threat by regional developments, illustrated by two hotspots in Northeast Asia: the Korean Peninsula and the Taiwan Strait.

The security situations of the two spots have deteriorated over the decades. Year 2022 alone witnessed a record number of missile launches by North Korea, and the largest-scale military exercises held in the vicinity of Taiwan by the People’s Liberation Army. When it comes to the longstanding Japan-China rivalry, Japan may arguably be counted as a third hotspot too. Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) vessels have repeatedly intruded into Japan-claimed waters and contiguous zone near the Senkaku Islands (also known as Diaoyutais). Last year alone, the CCG presence in waters around the Senkakus was 336 days — the longest on record.

More significant is the fact that those three hotspots are all related to China. Beijing has supported Pyongyang since the 1950s and prevented the fall of the Kim authoritarian regimes. Beijing has never abandoned its claim over Taiwan, and has not renounced the possibility of using force to compel annexation. Moreover, Beijing’s insistence on China’s sovereignty over the Senkakus has fueled apprehensions in Tokyo and compelled the latter to strengthen Japan’s overall defense, with a focus on its southwestern islands.

Nonetheless, despite the above-mentioned regional developments, South Korea’s Indo-Pacific Strategy does not define China as such. Instead of seeing China as a disrupter of regional order, in Seoul’s view, China is “a key partner for achieving prosperity and peace in the Indo-Pacific region,” the report states. By contrast, the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy report calls China a “challenge,” and the U.S. National Security Strategy labels China as a “competitor.” Likewise, Japan’s recently released National Security Strategy report (2022) refers to China as “an unprecedented and the greatest strategic challenge.”

The U.S. and Japan’s vigilance on China stems from the fact that China poses a threat and challenge to the world generally and to the Indo-Pacific in particular. South Korea’s Indo-Pacific strategic view of China therefore seems to be somewhat at odds with that of its allies and partners.

Moreover, the South Korean government’s view of China also stands in stark contrast with the negative perceptions of China held by a large segment of the South Korean population. According to a poll released in April 2021 by Hankook Research, a South Korean research firm, 83% of South Koreans surveyed regard China as a security threat to South Korea. Even in the economic sphere, 60% of South Koreans consider China a threat. A Pew Research Center poll released in June 2022 shows that 80% of South Korean respondents have a negative view of China.

Given China’s global economic influence, it is understandable that South Korea, a geographically close neighbor of China, has to maintain a sound (or at least stable) relationship with it. However, as South Korea looks to enhance its strategic autonomy, and as the structure of “security dependence on the US” is unchanged, it remains to be seen how much latitude Seoul enjoys to fulfill its view of China as a “key partner.”

In fact, the U.S. government is increasingly set against China’s international expansion, and has sent signals that there might be little room for a “China-friendly” South Korea whose need to militarily counterbalance China must also be taken into account. It also remains to be seen whether the report can succeed in convincing Tokyo and Taipei that South Korea would place Japan’s and Taiwan’s security interests above it economic relationship with its “key partner” in its strategic calculations.

Overall speaking, South Korea’s demonstration of its determination to commit to the region’s freedom, peace and prosperity is commendable. Its inclusion of the Taiwan Strait should be welcome by Taipei. Although further elaboration might have been needed in its references to China, future communication with allies and partners over the priorities in the policy goals laid out in the report may help address some of the unnecessary confusion.

(Dr. Wang is Associate Research Fellow, Institute for National and Defense Security Research.)