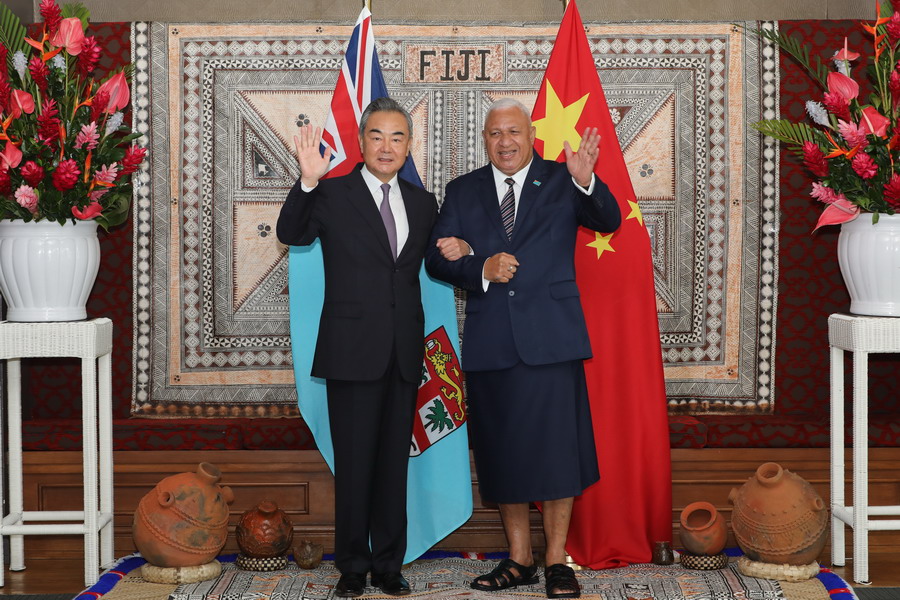

The cool reception from the regional leaders suggests strongly that Wang’s tour was miscalculated overreach in terms of Chinese expectations of what the regional leaders would deem acceptable for cooperation. Rather than being the anchor for the launch of a regional security agreement with the Pacific Islands, the Sino-Solomons pact appears to be the reef on which the broader ambitions may have foundered — at least for the present. Picture source: MOFA, PRC, May 30, 2022, MOFA, PRC, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/wjbzhd/202205/t20220530_10694447.shtml.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 41

Wang Yi’s Pacific Tour: Diplomatic Overreach or Temporary Setback?

By Richard Herr

The unexpected late May 2022 announcement that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi would undertake a 10-day visit to the Pacific set a rather high bar set for success. The Global Times reported that Wang’s trip intended to deliver “a strong and clear response to [the] US’ containment strategy.”

The foreign minister was expecting to prove that China had a legitimate and widely welcomed presence in the region despite perceived Western efforts such as the AUKUS agreement and Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in advancing the aims of the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” project which he saw as attempts to restrict the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) engagement with the Pacific Islands.

Wang’s tour was designed with two prongs. One was a series of bilateral meetings with virtually all the Island members of Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) that recognized Beijing. Face-to-face discussions were scheduled with Fiji, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tonga, Vanuatu, and virtual discussions with other regional leaders in the Cook Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Niue.

The second, and arguably more important, prong for achieving a diplomatic tour de force was the convening of the second China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers' Meeting which Wang would chair while in Fiji. This was expected to put the seal of approval on two wide-ranging regional agreements.

A “China-Pacific island countries common development vision” set out a set of claimed shared aspirations ranging over security, governance and development priorities. The second broad agreement offered a five-year action plan to implement the common vision.

In the event, Wang’s grand excursion failed to deliver on the lofty aspirations held for it.

Retrospectively, it might even be questioned as to whether there were reasons for believing the initial high hopes were achievable.

There were some signs that the PRC was on a roll regionally. The achievement of the Sino-Solomons security agreement buttressed by the dogged defence of the pact by the Solomons Government. This, coupled with the success in flipping two Taiwan allies — Kiribati and Solomon Islands — in 2019 and the PRC’s growing development assistance profile in the region, contributed to a sense that the time was right to push for more.

Time itself may have been a critical factor in trying to take the Solomons’ agreement to the next level. New Zealand Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta made clear in April that the security agreement would be a subject of review at the PIF’s July Leaders Meeting. China might counter this pressure by demonstrating regional support before the PIF meeting.

David Panuelo, the president of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), certainly saw a linkage between Wang’s tour aims and the Sino-Solomons’ agreement. He expanded on his letter only weeks earlier to Solomons’ Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare pointing out the potentially ruinous geopolitical consequences of the Sino-Solomons agreement with an even longer and stronger letter to 21 Pacific leaders censuring the Chinese regional proposals.

The tour was dogged with criticism both for its public and private diplomacy. A lack of transparency elevated regional suspicions. The contents of the proposed agreements apparently were leaked by a regional government rather made available by China. Media access to Wang was tightly controlled with few if any questions being allowed in most stops.

Moreover, there was a genuine fear that the official talks were mainly “theater.” A report circulated that Kiribati had to be pressured into relaxing its Covid restrictions to allow the Wang visit. The FSM was highly critical of being strong-armed by the circulation of a predetermined joint communiqué in support of the regional proposals prior to the meetings.

Wang’s regional gambit was effectively sidelined when Samoan Prime Minister Fiame Mata’afa argued convincingly that the Chinese proposals should be considered by the forthcoming PIF meeting not just at meeting with Wang by those states recognizing Beijing.

This was a significant if oblique expression of regional sentiment that blunted both Wang’s bilateral effort to build a bandwagon for the two regional initiatives and, very tellingly, put their fate into a process where China did not have a voice but Australia and New Zealand did.

Salt was rubbed into this wound when the scheduled post-PIF dialogue partners’ meeting was deferred so as to not follow immediately after the Leaders Meeting. A primary reason behind the schedule change was to avoid direct lobbying by the powerful dialogue partners states while the PIF leaders were meeting.

Unwilling to be frustrated entirely, the Chinese Communist Party's international department in Beijing hosted its own political dialogue with Pacific island countries on the same day as the Leaders’ Meeting in Suva to retain some regional initiative as well as to save some face. There was no real outcome beyond providing the Chinese mission in Fiji with fodder for a photographic tweet.

So, what is to be made of Wang Yi’s 10-day Pacific diplomatic excursion? By his own expressed criteria, the tour was at best “disappointing.”

Rather than countering the array of interests aligned against the PRC, the tour actually strengthened initiatives such as the establishment of Partners in the Blue Pacific mechanism by the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Australia and New Zealand to involve them more directly in regional development.

Moreover, the cool reception from the regional leaders suggests strongly that Wang’s tour was miscalculated overreach in terms of Chinese expectations of what the regional leaders would deem acceptable for cooperation.

It is difficult to know where responsibility for the erroneous political calculus rested. Very likely it has to be shared between a Beijing too anxious to lock in regional gains and the failure of its Pacific missions to prepare adequately for a successful outcome.

Rather than being the anchor for the launch of a regional security agreement with the Pacific Islands, the Sino-Solomons pact appears to be the reef on which the broader ambitions may have foundered — at least for the present.

Regional solidarity even forced a public rethink by Sogavare who on the very eve of the PIF meeting had expressed a desire for a closer and more permanent security relationship with China.

After the Leaders’ Meeting, the Solomons’ Prime Minister acknowledged the gravity of his security agreement admitting that his country would “immediately become an enemy” to Australia and other friendly states if he allowed China to establish a military base.

Sogavare’s public pledge that the Sino-Solomons pact would not lead to a Chinese military base allowed Australia’s new Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to change the tone of Canberra’s relations with Honiara by expressing his trust in Sogavare’s guarantee.

There is a limit as to how much can be read into the failure Wang’s tour to secure his main objectives. The 52 bilateral development agreements reached during the tour demonstrate that the Island countries value Chinese non-security assistance. In addition, the PRC has indicated that it will leverage its Belt and Road Initiative promote acceptance of a revised regional “vision.”

There are many lessons that the U.S. and all the traditional friends of the Pacific Islands might take away from Wang’s tour but the key one must be that their investment in regionalism has paid dividends. The sense of belonging to a security community limited the risks the Pacific Islands were willing to take with their safety in a changing and complex geopolitical environment.

The challenge now is for these traditional friends to support the Pacific states appropriately as they continue face new security challenges including adjusting to China’s persistence in seeking a larger role in the region.

(Richard Herr is Academic Director, Parliamentary Law, Practice and Procedure Course, Faculty of Law, University of Tasmania)