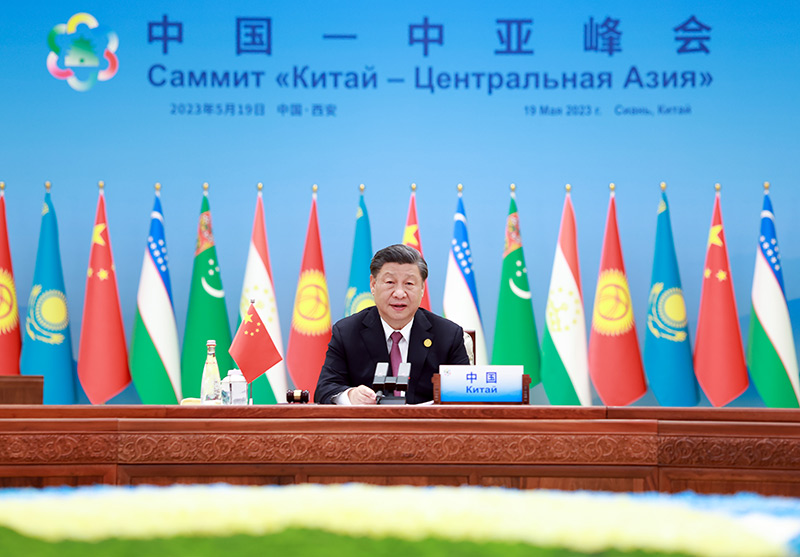

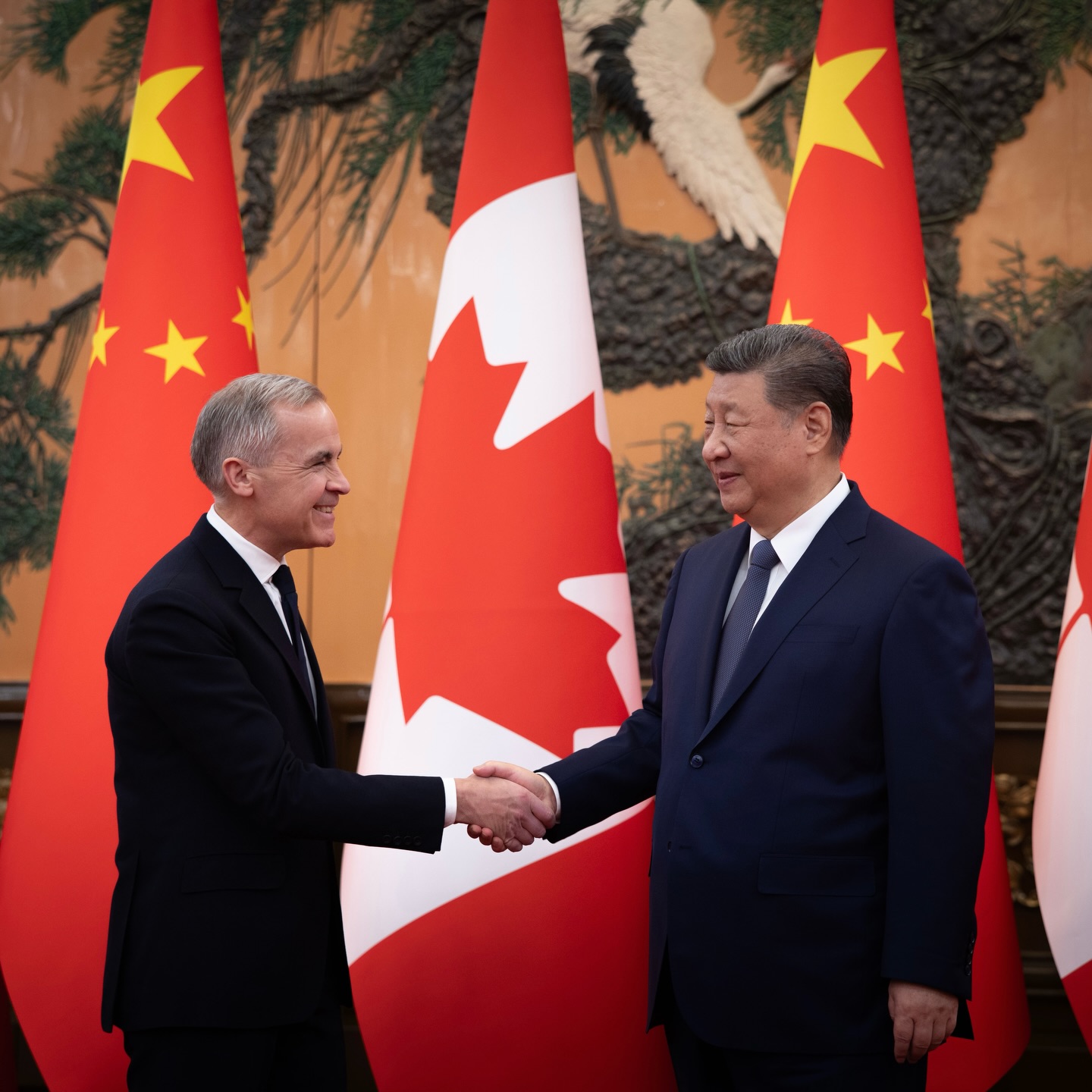

The outcomes and positive impressions of the Xi’an summit have boosted a sense of trust among Central Asian elites towards the PRC. There is only one tradeoff — by now, they are clear about the role they play in legitimizing Beijing’s leadership over Xinjiang (East Turkestan). Picture source: 劉彬, May 19, 2023, www.gov.cn, http://big5.www.gov.cn/gate/big5/www.gov.cn/yaowen/tupian/202305/content_6875104.htm#5.

China’s Proof of Concept in Central Asia

Prospects & Perspectives No. 34

By Niva Yau

It has been a little over a month since the Central Asia-China summit wrapped up in Xi’an. Since independence in 1991, regional ties with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have been on a singular path of progress, politically and economically.

Russia’s War in Ukraine for the first-time created sources of tension between the PRC and Central Asian states, as the former maintains tacit support for Russia while the latter suffers from the various economic impacts due to close ties to the Russian economy, as well as an ideological crisis over the place of Central Asia in global politics.

In the backdrop of intensifying outreach from other foreign actors such as the European Union and the United States, the Xi’an summit was designed to boost Central Asian confidence in the PRC. Where Europe speaks of connectivity projects to connect Central Asia with Turkey via the Middle Corridor, the PRC has already built such logistics routes and has now proposed plans to expand them. Where the U.S. speaks of human rights issues and reforms in Central Asia, the PRC offers authoritarian technologies and its controversial poverty alleviation programs that are attractive to regional leaders.

The Xi’an summit produced a total of 82 deliverables, doubling down on all sectors and areas the PRC has managed to build over the past 20 years. In essence, Chinese engagement in the region relies on a form of regionalism that promotes itself as the center of inter-regional exchanges. It allows each Central Asian country to work with the PRC in a way that is tailored to their needs – resource-rich countries such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan ask for technology and industrial transfer programs, the state budgets of the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan are severely dependent on aid, and all Central Asian countries across the region need modernization for their aging Soviet-era infrastructure.

As a whole, they build regional integration with the PRC in a flexible but holistic manner that is appealing to Central Asian elites, orientating the region eastward in a way that squeezes out any room for potential deviation from pro-PRC positions. This approach came after the PRC’s misplaced focus on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in the past two decades, trying to induce regionalism using a multilateral organization which serves very specific needs on security, and none that actually binds the region. While the PRC still maintain a preference for a regional format, it has recognized the lack of unity in Central Asia and therefore is now pursuing a strategy to build a form of regionalism that requires little internal exchanges — but one that promotes the PRC as the center of inter-regional engagements.

Compared to other parts of the Chinese neighborhood, the PRC has made some of the strongest inroads into Central Asia, an effort that is proving to be resilient despite global tensions. Political trust and regional stability — key vocabularies that marked regional relations over the years — were backed by significant economic incentives that fed and increased control of rent-seeking local elites who in turn cracked down on civil society to secure their local leadership. More cross-regional investment projects are now underway.

As a direct result of this, the willingness of Central Asian elites to work with their eastern neighbor has invited the PRC to experiment with normative agenda-setting, using the region as a testing ground for its global practices, which are now becoming a norm elsewhere. For example, at the onset of Central Asian independence, using selective stories, the PRC worked to induce an idea of “harmonious Silk Road” as an ideological foundation for making sense of strong regional ties to the East. In Sri Lanka, the PRC now stresses ties to the island-nation through “historical Buddhist ties,” framing itself as a Buddhist country despite its communist, atheist commitment.

Most importantly, in order to destroy the credibility of political movements and protests against ethnic-based discriminative policies in Xinjiang (East Turkestan), the PRC created and exported the idea of the “three evils” (extremism, terrorism and separatism) to Central Asia through the SCO in the 2000s. Since then, the PRC has put forward its new definitions of democracy and human rights at various international organizations. New vocabularies framing these concepts have emerged as well, such as the Global Security Initiative, the Global Development Initiative, the Global Civilization Initiative, as featured at the Xi’an summit and elsewhere.

Apart from these concepts, in Central Asia, through its ambassadors and media partnerships, the PRC actively engages in regional political narratives, i.e., the idea that Central Asian countries should pursue a stable, predictable society free of the chaos that supposedly accompanies democracies and framing any criticism directed at PRC conduct in the region as an attempt by malign actor to undermine bilateral relations and Chinese domestic developments.

As Russia’s War on Ukraine unfolds, Central Asian countries are facing great challenges in their developmental and political path moving forward. The most difficult task faced by Central Asian countries is not just about finding new economic partners in South Asia and the Arabic community to fill current needs, but exploring a long-term strategy that can increase prosperity of the region in a sustainable, holistic manner.

Given global tensions and failure to manage relations with the international community, it would appear that this sustainability calls for a strategy without committing to ever deeper economic ties with the PRC. However, outcomes and positive impressions of the Xi’an summit have boosted a sense of trust among Central Asian elites towards the PRC. There is only one tradeoff — by now, they are clear about the role they play in legitimizing Beijing’s leadership over Xinjiang (East Turkestan). As the Kyrgyz Republic enters the UN Human Rights Council this year, it is no wonder that, unlike other Central Asian counterparts, the Kyrgyz side went out of it way to emphasize at the Xi’an summit that it is willing to combat “East Turkestan separatists.” On China, Central Asian countries seem to all agree on the shape of the future.

(Niva Yau is a Nonresident Fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub.)