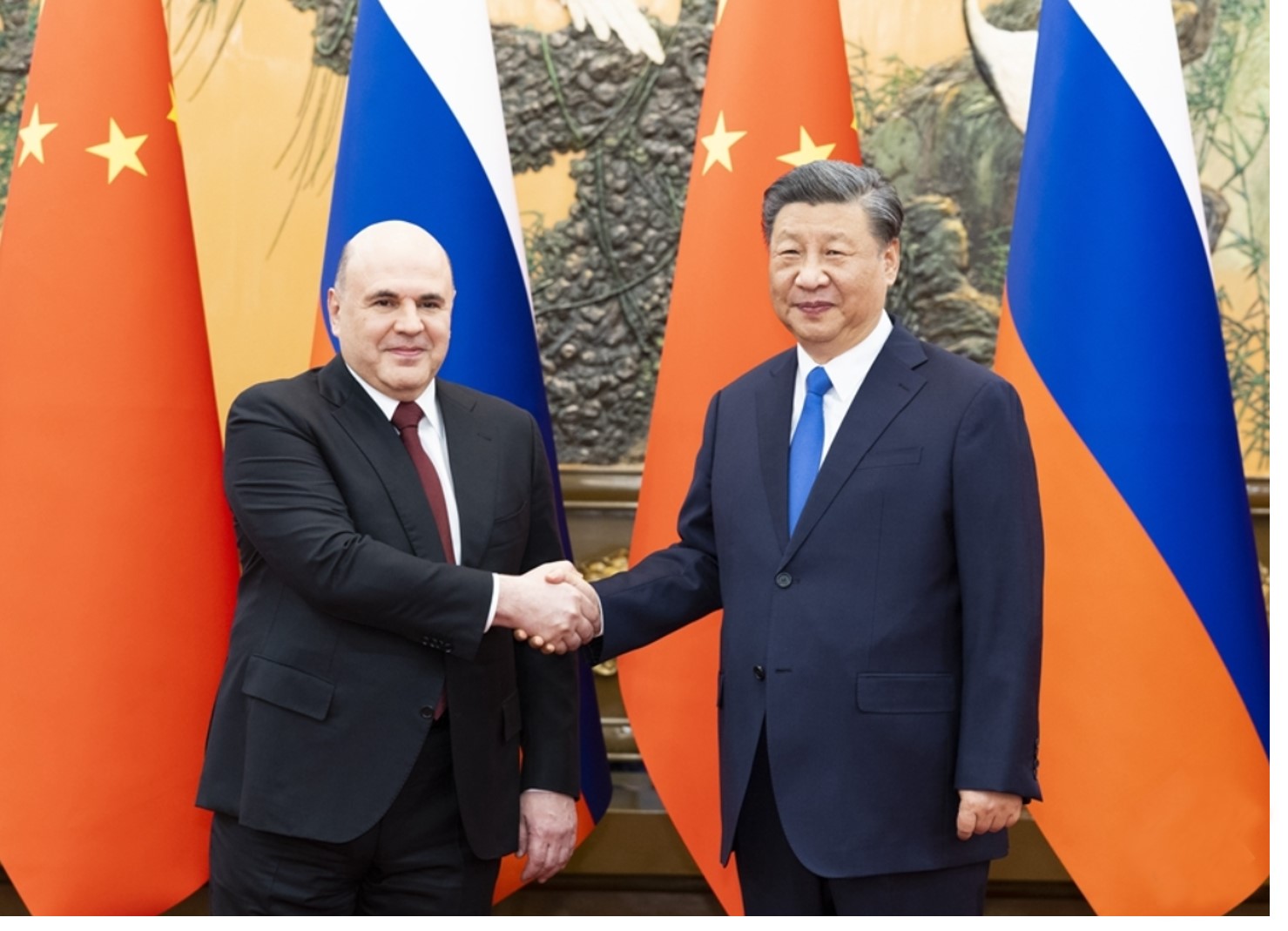

The PRC’s position on Russia’s invasion has walked a precarious line of neutrality while unofficially supporting Russia’s war effort. PRC’s peace plan called for actions such as not “expanding military blocs” (indirectly referring to the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) and an end to “unilateral sanctions” to curb U.S. and European economic pressure. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Fueling War: China’s Military Assistance to Russia

Prospects & Perspectives No. 46

By Michael A. Allen

In early 2023, the Biden administration and European leaders publicly warned the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that there would be “dire consequences” if it began to military support Russia in its invasion of Ukraine. These warnings came at a peculiar time as the United States actively sought to unthaw relations with the PRC; such warnings had the opposite effect.

The U.S. issued these warnings due to emerging evidence that the PRC was considering a larger push to help Russia’s effort in Ukraine. There was evidence that Russia received material support from Chinese state-owned enterprises that the PRC could credibly deny knowledge or approval of their actions. Washington was concerned that Beijing’s official policy change could give Russia the support it needs to continue its war successfully. Consequently, the U.S. wanted to stop an official change before it happened.

PRC ‘Neutrality’ and ‘Peace’

The PRC’s position on Russia’s invasion has walked a precarious line of neutrality while unofficially supporting Russia’s war effort. Diplomatically, it has claimed to be neutral on the conflict. By having a public stance of neutrality, the PRC has tried to use its position as a mediator in the conflict and propose a peace plan. However, this peace plan called for actions such as not “expanding military blocs” (indirectly referring to the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) and an end to “unilateral sanctions” to curb U.S. and European economic pressure.

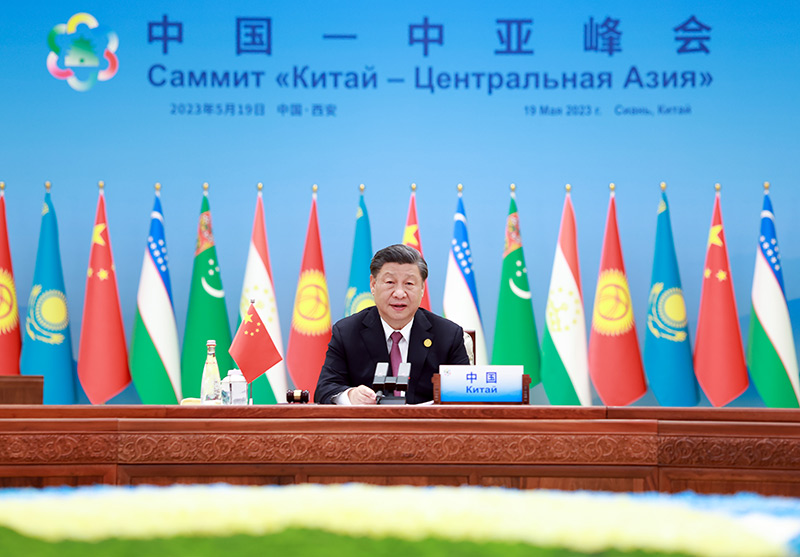

The joint declarations the PRC has made with Russia, the refusal of the PRC to condemn the invasion of Ukraine, the peace plan that would be favorable to Russia, the unofficial support of Russia’s war effort, and statements denouncing the West and the U.S. all demonstrate that the PRC is not a neutral party in this conflict. The PRC just hosted the 11th World Peace Forum in Beijing with some discussion of Ukraine by Russian speakers, but no Ukrainian speakers were on the agenda. After the failed Wagner mutiny in June, the PRC quickly released a statement supporting the Russian government. Former Foreign Minister Qin Gang highlighted Russia as “a comprehensive strategic partner of coordination for the new era” in his statement. In August, the countries conducted joint naval exercises near Alaska to show continued cooperation and mutual support.

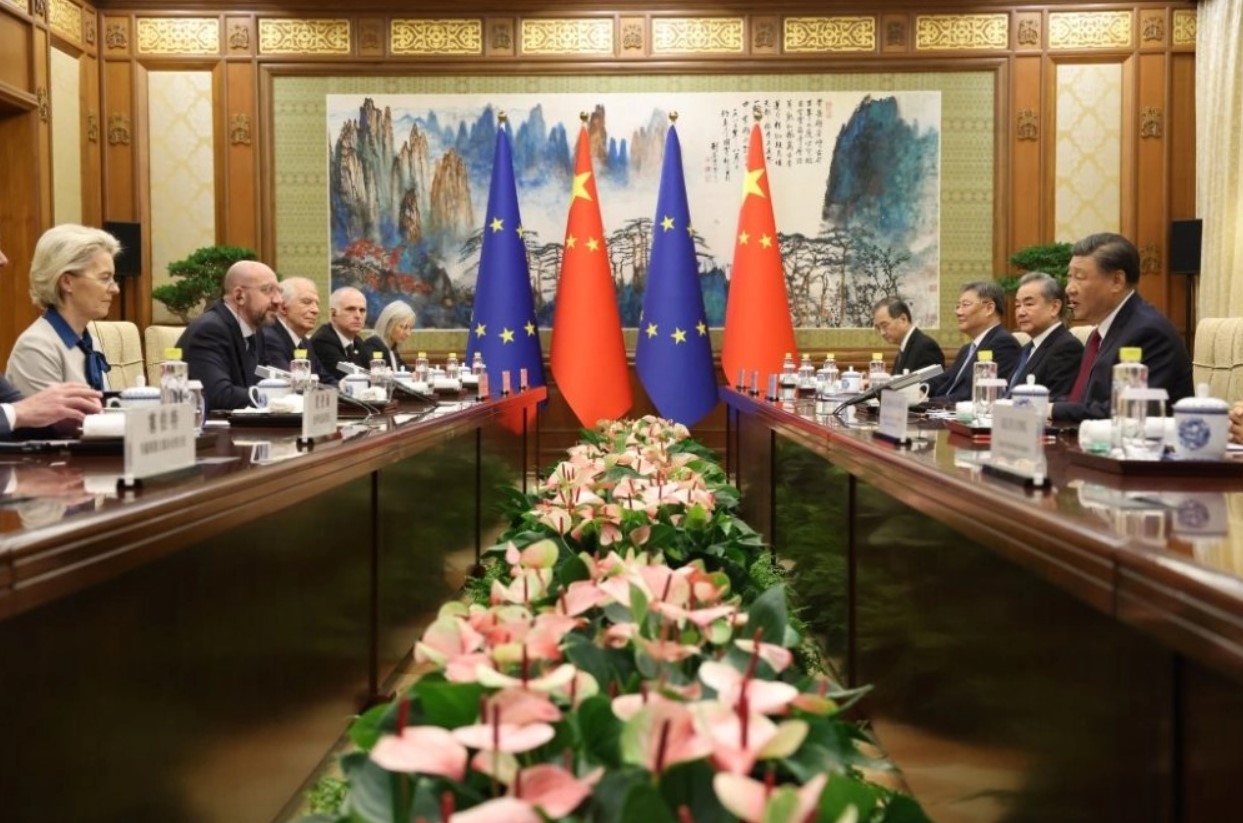

While the PRC is attending a series of peace talks in Saudi Arabia that does not include Russia, this does not show a shift in its support of Russia. Instead, it indicates that the PRC wants to continue to sit at the table in such discussions and offer favorable solutions to Russia and, by extension, President Xi’s preference over world affairs. Foreign Minister Wang Yi has assured Moscow that Beijing would be an “objective and rational voice” in this new round of negotiations.

Russia’s success or failure in its invasion of Ukraine has clear implications for how the PRC views evolving great power competition and future relations between the PRC and the Republic of China.

Beijing’s Hope, Ukraine, and Taiwan

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, Vladimir Putin and President Xi met at the Olympics and released a joint statement about their shared vision of world politics. Their statement highlighted a world where Russia and the PRC were becoming more powerful, the U.S. was receding from its dominant position, and the two countries would commit to a “no-limits partnership.” If these trajectories of power meet Russian and Chinese expectations, then it is an opportune time for the two countries to promote their values, views, and desires. Notably, this includes their views of what the proper borders of each country ought to be.

There was a consensus that the Russian force was far superior to the Ukrainian force and that Ukraine had little hope of defeating Russia’s invasion. Russian planners expected the war to be quick and perhaps mirror its previous acquisition of territory in Crimea and Georgia; its military forces would meet little resistance, and the invasion would be over in days or a few weeks. Ukraine’s ability to repel Russian forces from taking Kyiv and sustain fighting for over 18 months was largely unexpected.

For the PRC, every aspect of the Russian invasion has potential lessons for war planning in Taiwan. While, internally, there is an acknowledgment that Ukraine is not Taiwan, this is an aspirational mantra as much as a practical one. The PRC hopes that it will be more successful in Taiwan than Russia is in Ukraine. However, several factors from the Russian invasion will prove pivotal to the PRC’s calculus going forward.

First, expectations of a quick war were wrong. Despite Ukraine’s smaller size, military, population, and economy, it could still resist a Russian invasion. While the war outcome is not yet determined, it has proven to be costly to Russia regarding life, military assets, and money. Taiwan’s location, defenses, international support, and the uniqueness of its economy should also make any such provocations undesirable. Even if Beijing were to acquire the Taiwanese semiconductor sector through force without actual damage to the industry, Beijing’s isolation in the semiconductor supply chain would doom any hopes of long-run production or capabilities.

Second, the Western response to Ukraine was unprecedented. Despite Russian attempts to sanction-proof its economy, it could not anticipate how massive the economic retaliation has been, and its economy has crushed the price of the Russian ruble and caused general inflation in its economy. While India and the PRC have kept the Russian economy afloat to a large degree, it is in far worse shape than before the war. This response may have set a new precedent against territorial aggression.

While Russia was able to find support from Beijing during its isolation, it is not clear who Beijing could turn to if it were to face similar isolation. While Russia would be the obvious choice, it will take decades for Russia to be in the economic, financial, and military position it was in before the invasion of Ukraine.

Third, Beijing’s attempts to normalize the invasion and create a peace deal that formalizes Russian territorial grabs have floundered. It would create a blueprint for any PRC invasion of Taiwan if it were to succeed. However, the PRC’s inability to find support for its efforts leaves doubt as to whether it could go back to “business as usual” if it were to invade the island nation.

Russia’s invasion has left Beijing in a difficult position where it is backing a side that is underperforming expectations and is wildly consuming scarce resources in its campaign. Russia relies on the PRC, and the PRC wants Russia to succeed. Success for Moscow means success for Beijing’s vision of global affairs and a blow against security networks in Europe and Asia. Despite this preference, Beijing has played a diplomatic game by not sending arms to Russia thus far and vying for a leadership role in peace negotiations.

The worst possible outcome for Beijing would be for it to start arming Russia officially, but Russia fails in its campaign regardless. Russia’s ineptitude on the battlefield is one thing, but failing while being supported by the PRC would send a global signal that Beijing supported the wrong side and that its support was not enough.

(Dr. Michael A. Allen is Professor of International Relations in the School of Public Service at Boise State University.)