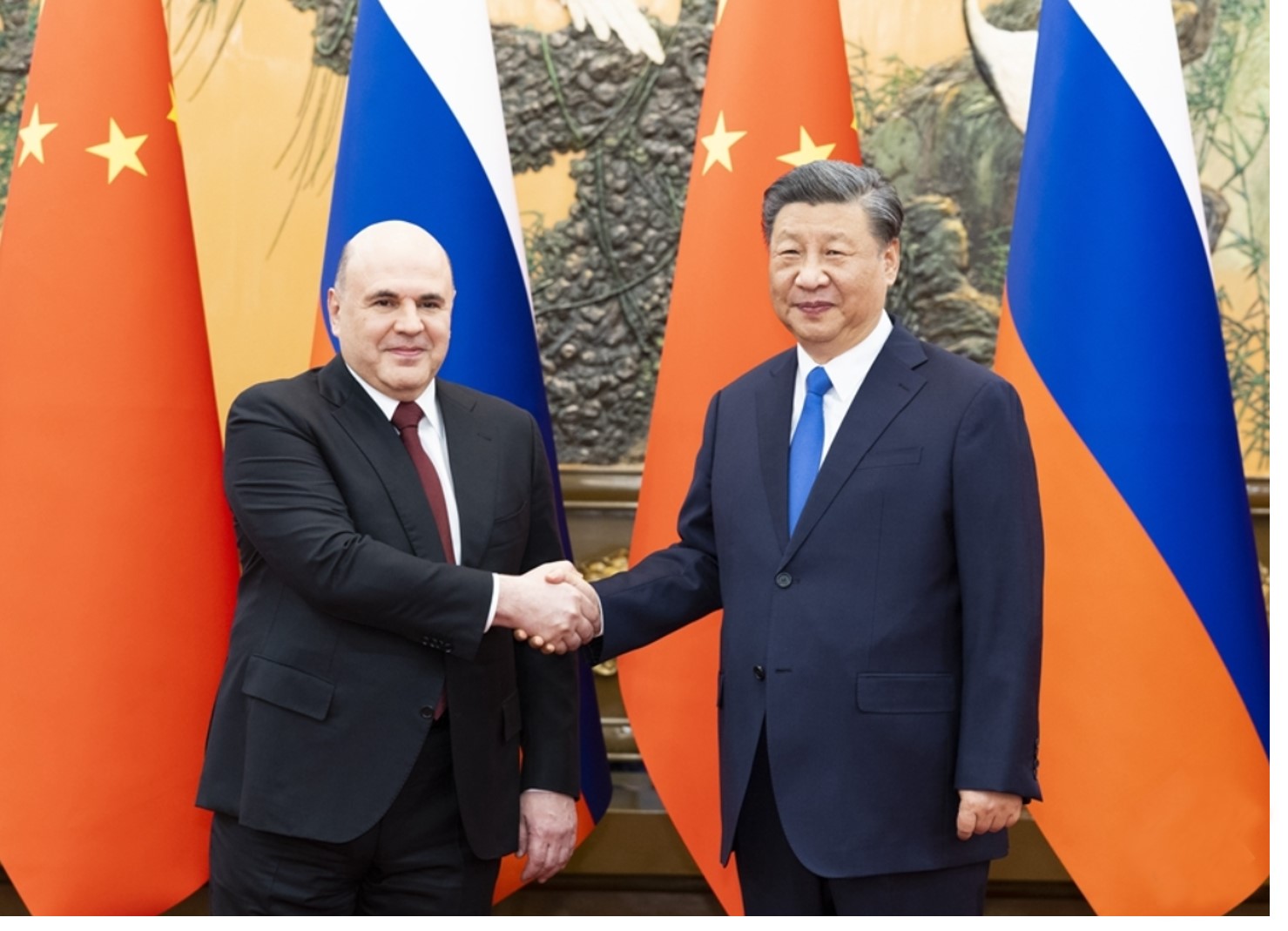

In view of the Russian threat, an expansion of NATO to include the Scandinavian countries is all but given. Moving forward, NATO’s objective will not only be to contain the security threat posed by Russia, but also stand as a pillar defending the international liberal order and values. Picture source: NATO, May 26, 2022, NATO,

Prospects & Perspectives 2022 No. 33

NATO’s Role in a New World

By Jagannath Panda

June 10, 2022

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which emerged as a mechanism to counter the Soviet Union (USSR) during the Cold War, has long been a core institution representing the strength of the transatlantic partnership. Since the end of the Cold War, however, the role of the organization in the region, as well as the objectives it should focus on and the potential consequences of its gradual but undeniable expansion, have been a matter of intense debate. Where does NATO stand today, in a new vastly changed international security landscape, and what are the prospects for its expansion?

Although the U.S. stated several times that the NATO would not expand eastward and threaten the Russian Federation in any way, over time, several eastern European states have become part of the organization. NATO’s “open door policy” – which states that any “European state in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area” (Article 10) – has resulted in the body welcoming a number of former Soviet satellite states into the fold.

This has naturally been a major point of contention for Moscow; most Russians still view NATO as a “vestige of the cold war, inherently directed against their country.” Therefore, the ascension of Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia only served to intensify Russia’s original concerns over NATO’s expansionism, further spurring nationalist, anti-Western and militaristic sentiments in the country. For Moscow, NATO’s expansion brought the security threat posed by the organization directly to its border, making it feel encircled and resentful that the states in Russia’s periphery were now a part of an “adversarial” alliance.

In fact, many have argued that the invasion of Ukraine was a direct result of Russia’s frustrations and insecurity over NATO’s expansion. However, paradoxically, for several Western states Russia’s military operation in Ukraine was only proof of the importance of a strong and robust NATO alliance, as well as the necessity for its expansion. It brought into focus the value of global alliances in guaranteeing peace, security and stability through deterrence against autocratic powers.

Scandinavia’s NATO Bid: A New Era

After years of peaceful co-existence between Finland and Russia, and Sweden’s staunch neutrality, the two Nordic countries have submitted applications to join NATO. Public support has jumped since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and it reflects a wider trend across Europe. Denmark voted in a historic referendum on June 1 to get rid of the 30 year “opt-out” from the EU Common Security and Defence Policy it has reverently guarded due to its NATO membership and Atlanticist leanings. For Prime Minister Frederiksen, the change comes down to Denmark wanting to be united with its neighbors in the ‘‘fight for security in Europe.’’ The general trend is a timely reaction to the invasion of Ukraine as European states’ perception of security has shifted and they are looking to NATO and the EU for protection. The shock of the invasion to most European governments has significantly changed the European security order. Suddenly governments are willing to comply with the 2% defense spending for NATO when they previously would not.

Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO will significantly strengthen the alliance and secure its members. They will increase NATO’s capabilities, giving it greater control over the Baltic region and ability to support members like Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Overall Moscow’s position in north-eastern Europe will be weakened and with Finland joining, NATO’s boundary with Russia will doubled. The Nordic region has been previously characterized as a “strategic gap” where NATO defensive power is significantly outnumbered by Russian forces. Sweden and Finland will bring more security and stability to the Baltic Sea as Moscow’s Baltic fleet will become encircled in Kaliningrad. Their membership increases NATO’s ability to defend the Baltic and so it is being welcomed, especially as they already have very close cooperation. Nevertheless, Russia has already threatened consequences for their joining, and we might expect the build-up of troops and missiles on the Finnish border, along with increased cyber-attacks as retaliation.

NATO’s Expansion in the Democracy vs Autocracy Debate

NATO expansion also strengthens the EU as a pillar of NATO, which is good for the security architecture of Europe. However, the EU needs to continue from now to act united and move beyond the previous tensions between EU strategic autonomy and the strengthening of NATO that has held security and defense back in Europe. The divide between Atlanticist and Europeanist EU Members has undermined unanimity. Without this drawback, Europe can capitalize on the combined strength of European security that complements an enlarged NATO.

On one hand, NATO enlargement is about reducing the treat of Russia but is also about strengthening the defense of the liberal order and values such as sovereignty and territorial integrity that have been violated in the case of Ukraine. Yet, these are Western-centric and in bolstering their protection through alliances of like-minded states it does create a more divided world. NATO expansion will inhibit any future efforts to integrate Europe and Russia, as it sets them further apart, and creates the perception of a division in Europe (and beyond) between authoritarian, revisionist Russia and the European democracies isolating and encircling it. NATO expansion will only deepen Russia’s relationship with China and other authoritarian allies as a result of its alienation and threat perception. Thus, NATO expansion is about wider threats to the international order, wherever they occur, and is why many forms of security alliances and agreements are emerging all over the world.

Since its inauguration, the Biden administration has centered around the “democracy vs autocracy” calculus, but it has been particularly salient in his political rhetoric in light of Ukraine. Defending democracy was used as the preface for releasing the original American warnings and intelligence on Russia’s build-up at the Ukrainian border and has been used by the U.S. time and time again to garner support with its allies and partners. Fears of expansionist authoritarian rule have surfaced since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and it has renewed to many the need for NATO and unified democracies in Europe and beyond.

NATO in Beijing’s Global Outlook

Certainly, Beijing would argue that NATO is using the situation in Ukraine as momentum for enlargement in Asia and globally. China supports Russia’s claims that NATO’s expansion triggered the Ukraine invasion and believes that similar U.S.-led alliances pose a threat to Beijing. The Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in March that he believes that ‘‘the real goal of the US Indo-Pacific strategy is to establish an Indo-Pacific version of NATO,” because the strategy imbibes “bloc politics.” Similarly, senior Chinese diplomat Le Yucheng has described the U.S.’ Indo-Pacific strategy to be as “dangerous” as NATO eastward expansion, leading the region to “fragmentation and bloc-based division.” China has long criticized the Quad as an “Asian NATO,” but also feels that alliances such as AUKUS and Five Eyes are also intended to suppress China.

Beijing sees the U.S. as attempting to push China into a corner and surround it with American allies, and so, as a result, China is also trying to enlarge its own sphere so that it has countries to rely on. The deepening partnership with Russia is a key example, but so too is the security agreement Beijing has signed with the Solomon Islands. Worries are circulating that China is attempting to displace the U.S. and Australia as the primary security partners in the Pacific and this agreement will lead to a domino effect as China builds up its own “bloc.” Beijing has also expressed intentions to become even more self-reliant to resist sanctions or actions by “anti-China” groupings.

The Indo-Pacific is a volatile region with many “hotspots” where repercussions of the Ukraine War are anticipated to fall. As such, many Asian countries are already increasing their defense spending and looking for protection, which could result in a form of expanded NATO or “Asian NATO,” though the chances are very dim in near future. For the first time, South Korean and Japanese Foreign Ministers were invited to join the NATO Partner Session in April which discussed Ukraine and the international security situation. Foreign Minister of Japan, Hayashi Yoshimasa, has stated that he supported “concrete cooperation for NATO’s further enlargement in the Indo-Pacific to establish a new international order based on the rule of law…(and) cooperation for realizing a FOIP.” There are similarities between Russia and China that may be drawing Asian countries into the idea of a NATO-like protection – military posturing and expansion (even deadly incidents such as Galwan 2020), economic might, and increasing strength. Moreover, China’s backing of Russia has demonstrated that it does not respect the liberal international order and raised significant concerns for peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait and South and East China Seas. The Quad is the closest entity but it does not have the same security aspect as NATO yet, rather Indo-Pacific security is currently based on U.S. military bilaterals with Japan, South Korea and Australia, but not India.

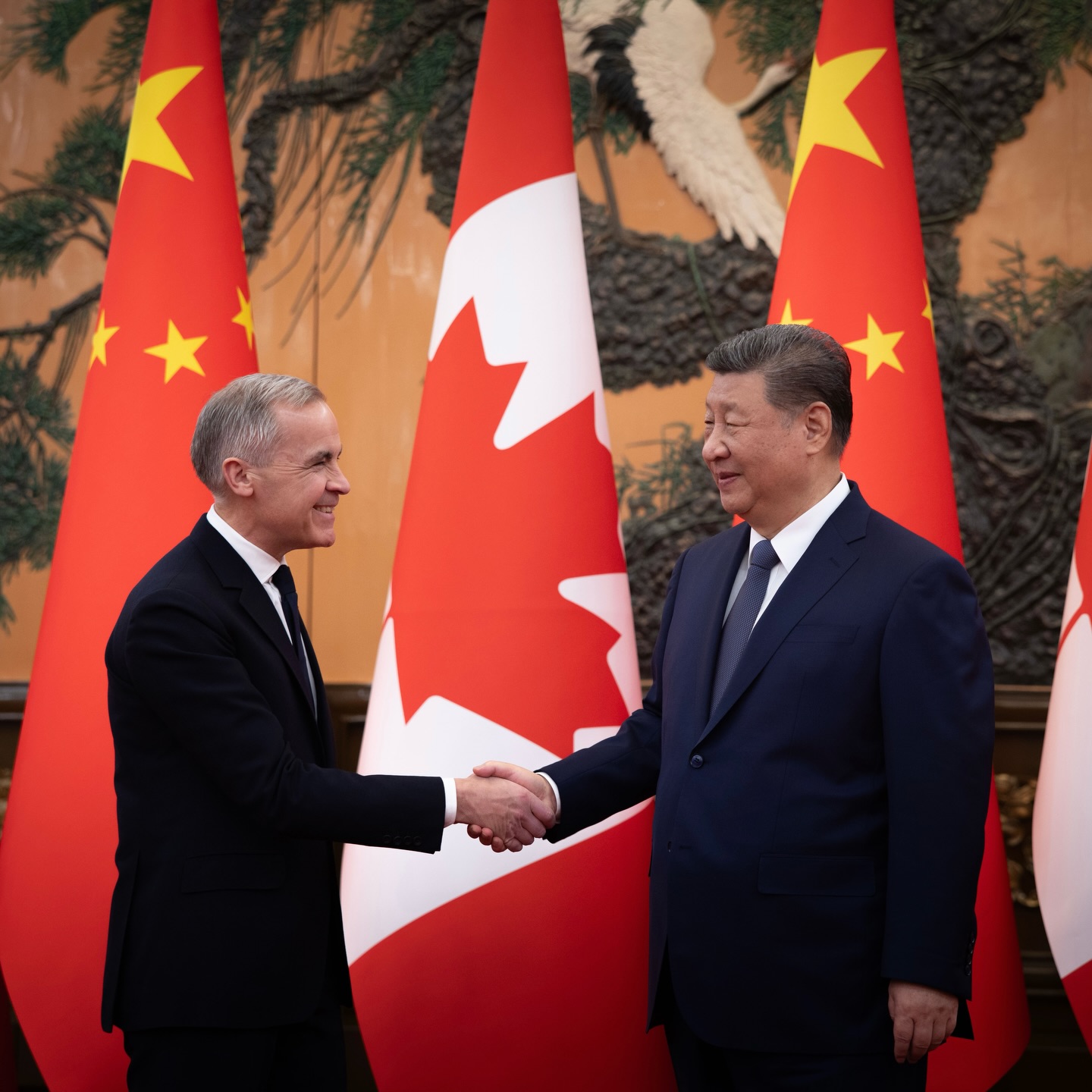

China already feels the U.S. is drawing Europe into its “bloc” that will ultimately be aimed against Beijing. Chinese Foreign Wang has accused the U.S. of “fabricating” a China threat that was to blame for the deterioration in China-EU relations, as visible in the strained nature of their recent summit. Growing synergy between Europe and Asian allies has been visible since the invasion of Ukraine. In April, Indian and Japanese leaders carried out meetings with European states over their mutual concern for Moscow and Beijing’s relationship. Kishida was in Germany and Modi met with leaders of the Nordic countries as well as Germany and France. Alongside the EU’s growing interest in the Indo-Pacific, many individual European states already consider themselves as “Indo-Pacific powers,” such as France and the UK which is part of AUKUS and Five Eyes.

However, for Europe, despite the economic and security challenges that China poses, it remains a distant threat. At present, the Ukraine war has refocused European attention squarely on Russia, which poses a much more immediate threat to European security, both in the traditional sense and in terms of its energy security. While Brussels (and individual European powers) may be displaying a tilt towards the Indo-Pacific, including through new initiatives like the “Strategic Compass,” they remain opposed to confronting China through NATO – or a NATO-like bloc in Asia. An “Asian NATO” would be overtly anti-China, and therefore not something that Brussels will be comfortable with. Therefore, the EU is in no way looking to be part of “bloc politics” against China, but will rather look to work with the U.S. through broader Indo-Pacific initiatives such as the “Quad Plus,” which will allow it to retain a relationship with China despite growing competition. As President von der Leyen stressed in her opening speech at the Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi in April, it is important that in Europe and the Indo-Pacific “spheres of influence are rejected.”