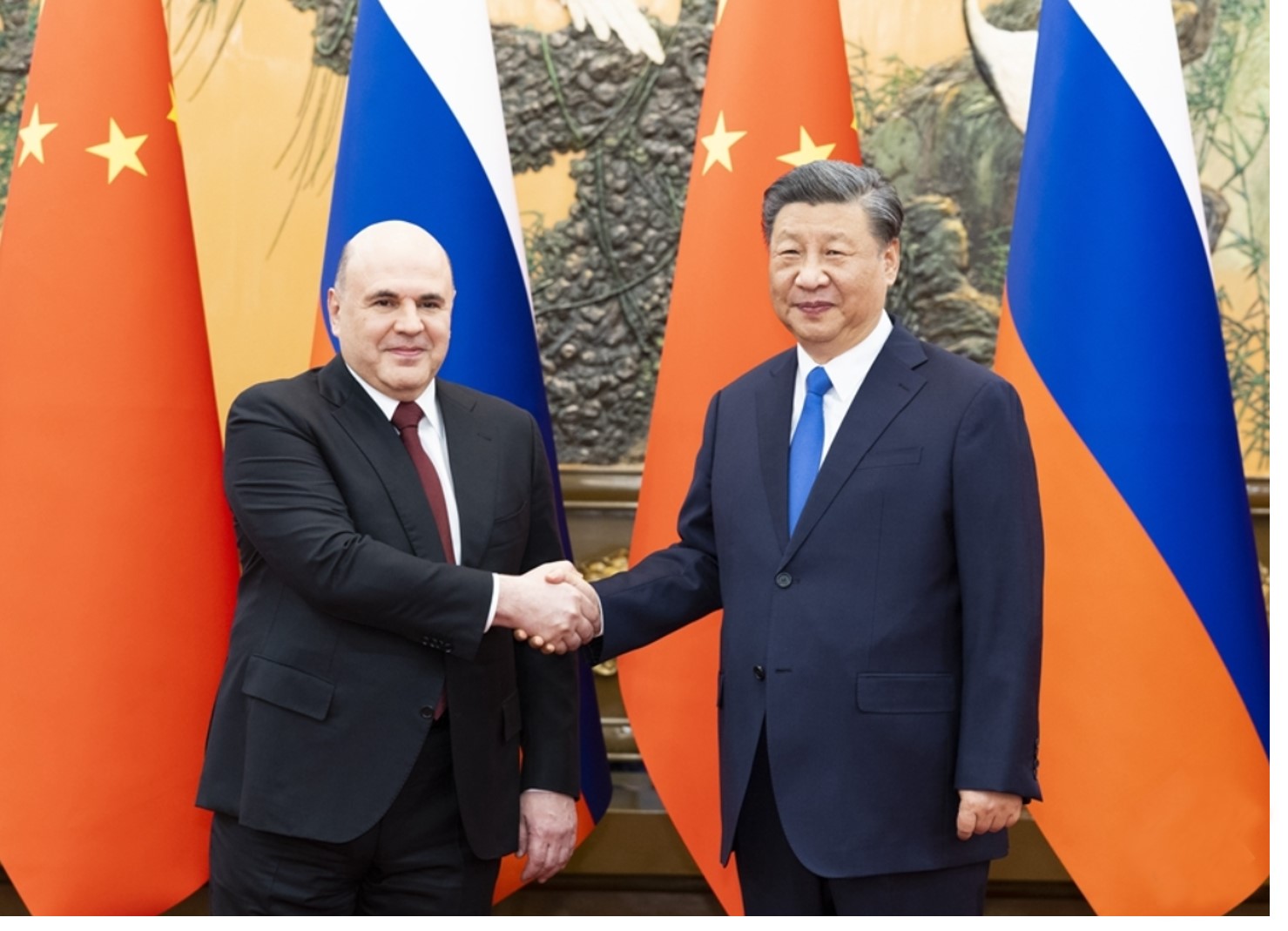

Even with the SCO summit meeting being one of the few opportunities for Modi, Xi, and Putin to interact constructively, the hostile India-China bilateral relationship and the complexities associated with Russian’s escalations in the Ukraine war, the SCO is quickly becoming a playground for competition and contestations between major powers, rather than a bilateral, regional, and global balancer. Picture source: Official website of India’s Presidency in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization 2022-2023, July 5, 2023, https://indiainsco.in/home.

The SCO: Whither Balancing?

Prospects & Perspectives No. 40

By Jagannath Panda

This was more so because Chinese hostilities at the Himalayan border have continued unabated: The last escalation was the Tawang clash in December 2022, and the timing – shortly after the brief exchange between Prime Minister Modi and Chinese leader Xi Jinping along the side lines of the G-20 summit in Bali – did raise speculations of China’s mal-intent. A piece in the Global Times also argued about India needing China’s support for carrying out its twin-presidency duties effectively, hinting possibly that repeated clashes will not bode well for India’s such high-profile global endeavors. In the SCO particularly, China’s financial clout over Belarus, Central Asian states, Russia, and Iran spells trouble for India.

Against this scenario, what do the latest SCO summit outcomes highlight? Does the forum’s expansion into a “Eurasia forum” lean more toward China and away from Russia? Importantly, is India withdrawing from taking a direct interest in the SCO?

Parsing the Delhi Summit Outcomes

The 23rd SCO Summit (Heads of State Council) meeting, hosted virtually in the first week of July, was the final event under India’s presidency that led to the New Delhi Declaration and two thematic joint statements (namely countering radicalization and digital transformation). Other key initiatives that were adopted include 1) digital public infrastructure (DPIs) development to advance digital inclusion and innovation; 2) emerging fuels collaborative projects; 3) climate action including combating pollution and advancing circular economy; 4) sustainable, decarbonized transport infrastructure; and 5) first-ever report on digital financial inclusion policies among the members. In addition, two working groups on startups and innovation and traditional medicine were also established.

At the outset, such a consensus on older SCO aims (anti-terrorism/separatism/extremism) and newer paths (digitalization) reflects decent gains in a divided forum. But the lack of concerted statements on economic and food security, which were expected until May, highlights the glaring lacunae and a missed opportunity. Further, India’s intent to modernize and reform the SCO for more “inclusive” regional growth has fallen flat. For example, efforts to include the use of English (besides Mandarin and Russian) and India’s artificial intelligence-based language platform, “Bhashini,” in the SCO workings, as also highlighted in Modi’s speech, have not achieved consensus, as yet.

As expected, India continued with its principled rejection of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the Declaration due to its opposition to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor that violates India’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. Another lag was India’s objection to the SCO Economic Development Strategy for 2030, reportedly due to the inclusion of “Chinese characteristics,” a move that has been heavily criticized in Chinese media as India’s “China hypersensitivities.” For India, China’s insistence on having its imprint on all things important seems to be a key impediment to SCO’s glaring lack of consensus.

Expanding Woes for India: Russia & China Will Rule the Roost?

The non-Western world’s interest in forums like the SCO and BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa) has been apparent in recent years. In the latest SCO workings, observer states are being granted membership – Iran was finally inducted as a full time member in July and Belarus signed a memorandum of obligation (full member by 2024). The drastic increase in dialogue partners (from six to 14 within a short span) and observers (three at present; six in process) is another sign of the expanding trajectory.

However, the composition of the new membership raises questions, not just for the West, but for India as well. Iran, which shares a cordial partnership with India via, for example, important connectivity projects including the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and Chabahar Port, aligns closely with China and has been backing Russia militarily – Iran is also part of a security-related pact with the two allies. In tandem with India’s bonhomie with the U.S. and Israel in West Asia (including the new “Quad” I2U2 that involves the UAE), the India-Iran equation is complicated to say the least. Moreover, Iran is peeved about India not supporting Iranian oil trade post Western sanctions like it has done with Russia.

The future member Belarus is another authoritarian state with deepening defense cooperation with Russia and economic ties with China. At the moment, Iran’s continued support for China and Belarus’s to Russia makes it even for the two dominant SCO partners – China and Russia will always be wary of the other’s increasing clout. Of the other two observer states, Afghanistan under the Taliban is cause for security concerns for the neighbors, including Russia; but China has been engaging the internationally isolated regime (e.g., China-Afghanistan-Pakistan cooperation mechanism). In contrast, Mongolia that is somewhat trapped between the Russia-China dependence and a democratic system will need to carefully hedge its bets.

The Summit also saw Russia and China vie for an upper hand, as Putin sought to contend that Western sanctions were only making Russia stronger, and Xi used the opportunity to convince member states to “de-dollarize” by conducting trade in local currencies. On the other hand, India’s chairmanship of the grouping proved to be controversial amidst the last-minute decision to shift the meetings online: India’s currently tense geopolitical relations with China and Pakistan; the staidness with Russia, and a bid to avoid the complications including the optics of Putin visiting Delhi; and the new normal with the US post Modi’s state visit seem to have certainly colored India’s outlook for the SCO. These developments make one thing clear: the SCO currently stands at a critical juncture as the relationship between three of its largest member states – China, Russia, and India – hangs in delicate balance.

At the same time, India’s goals via the SCO have been to ensure it has a voice in shaping the platform and – more importantly – preserve its own influence and build new linkages with Eurasia. With Moscow’s help, India had hoped it would be able to manage China and the threat its growing clout poses. But India’s close relationships with its Western partners, including the United States and European states (which are also North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO] powers), only complicates its engagement with the SCO. In this context alone, the expansion of the SCO has become a political point of contention, with each power attempting to ensure that new members are included strategically, in a way that supports their interests. Today, the SCO, therefore, stands as a vitally important platform for the foreign policies of all three powers as they seek to build substantive inroads in the Central Asia/Eurasia. In short, the future of the grouping will be punctuated by the geopolitical dynamics within and outside the SCO – including the evolving, but mostly plateaued (i.e., tense India-China; warm Russia-China; cordial Russia-India) India-China-Russia triangularity.

Whither Balancing?

At the same time, the SCO’s potential as a balancing force cannot be ignored even though it is not a forum to resolve bilateral disputes. That it brings together China, Russia, and India under one umbrella helps position it as a dialogue-oriented cooperative forum; so, it can help de-escalate tensions if not facilitate military disengagement. Moreover, the SCO (as also BRICS) has the opportunity to rebuild into an influential non-Western bloc that can benefit the Global South immensely – something that needs to be held on to despite China and Russia’s bluster.

Yet, even with the SCO summit meeting being one of the few opportunities for Modi, Xi, and Putin to interact constructively, the hostile India-China bilateral relationship and the complexities associated with Russian’s escalations in the Ukraine war, the SCO is quickly becoming a playground for competition and contestations between major powers, rather than a bilateral, regional, and global balancer.

Greater Good No More

Undoubtedly, in the SCO, the divergence among members is more complex and challenging: besides India’s hostilities with China and Pakistan, the former Soviet Republics also have unresolved conflicts. All the Central Asian member states have balanced their ties with Russia-China on the one hand and the US on the other; none has completely endorsed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In this context, a common concern among the SCO leaders was economic, food, and energy security, which have all been significantly impacted in the post-pandemic world. This was in line with India’s priority as the SCO Chair with the “Toward a SECURE SCO” theme. Yet the dissonance, primarily due to the China factor (e.g., financial clout in Eurasia or convergence with Russia), was visible during India’s SCO presidency.

Finally, notwithstanding the need for basic securities in an unstable region, it is clear that the longer the war in Ukraine extends, the harder it will be for India to not only sustain its deft diplomacy on Russia but also to sustain viability in China-dominated forums, particularly the SCO. As it will be for other Central Asian members, who in this sliding economic climate would not want the SCO trajectory to get steamrolled by China and Russia’s hardened anti-West stance.

(Dr. Jagannath Panda is the Head of Stockholm Center for South Asian and Indo-Pacific Affairs at the Institute for Security and Development Policy, Sweden, and a Senior Fellow at The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, The Netherlands.)