The Limits of Declaratory Summitry: Another Year, Another ASEAN Meeting

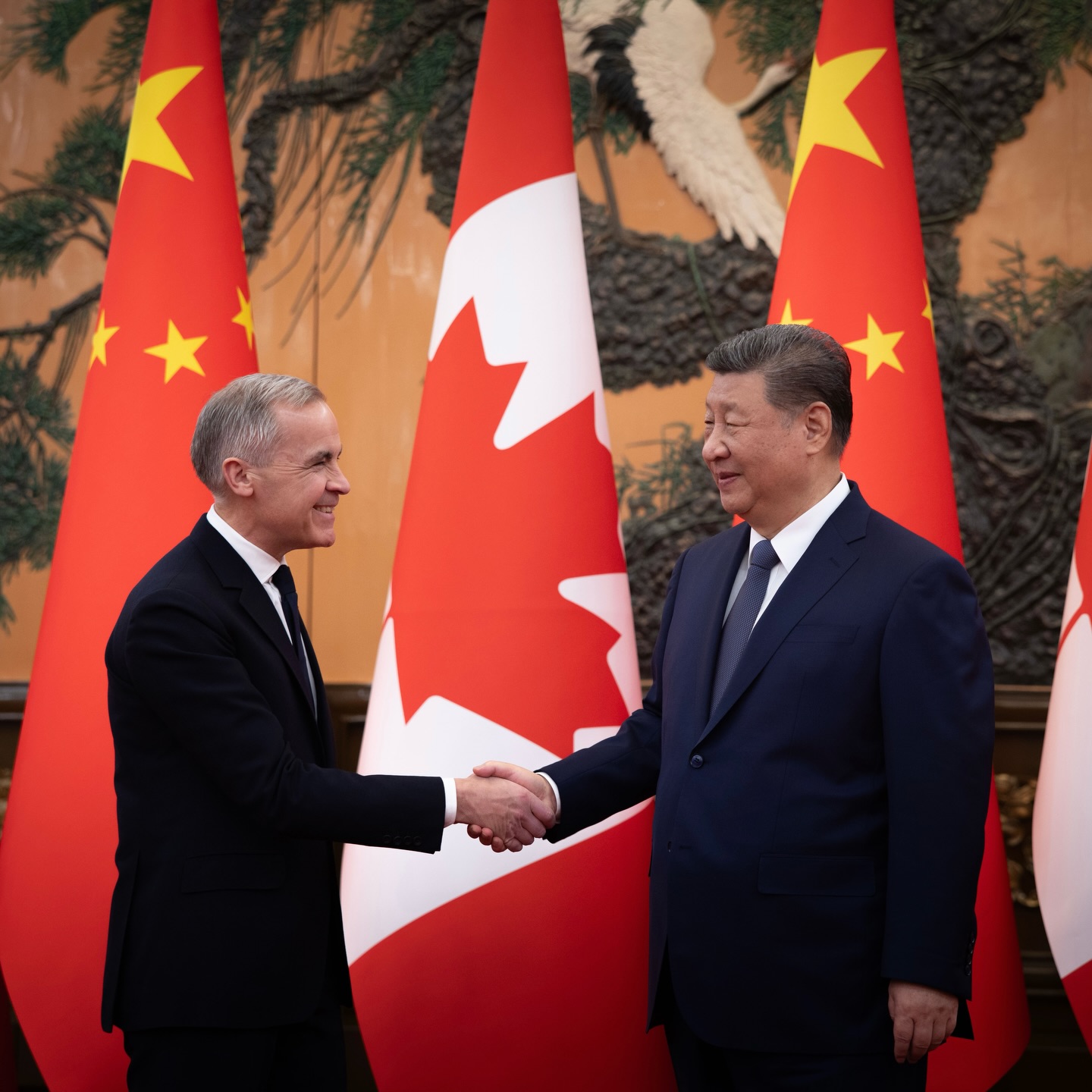

Despite the many concerns articulated by ASEAN and its members over the course of the 2023 summit, how they intend to achieve these declaratory goals is unclear. Such conditions reasonably raise questions about whether the grouping and its members have the political will to achieve their stated goals, or whether the lofty aims discussed at this year’s summit are mere wishes, much like similar statements issued in previous years. Picture source: Depositphotos.

The Limits of Declaratory Summitry: Another Year, Another ASEAN Meeting

Prospects & Perspectives No. 28

By Ja Ian Chong

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) saw the conclusion of its 2023 Summit on May 11. The forty-second iteration of the event brought together leaders from nine of the 10 ASEAN members states (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) along with the observer state slated to join the grouping, Timor Leste. Myanmar’s full participation remained blocked due to the coup and the continued civil war that resulted. Documents produced from the summit were wide-ranging, seeming to touch on a range of important topics for Southeast Asia and beyond. Whether any practical changes, even incremental ones, result from these statements and declarations are at best unclear, however.

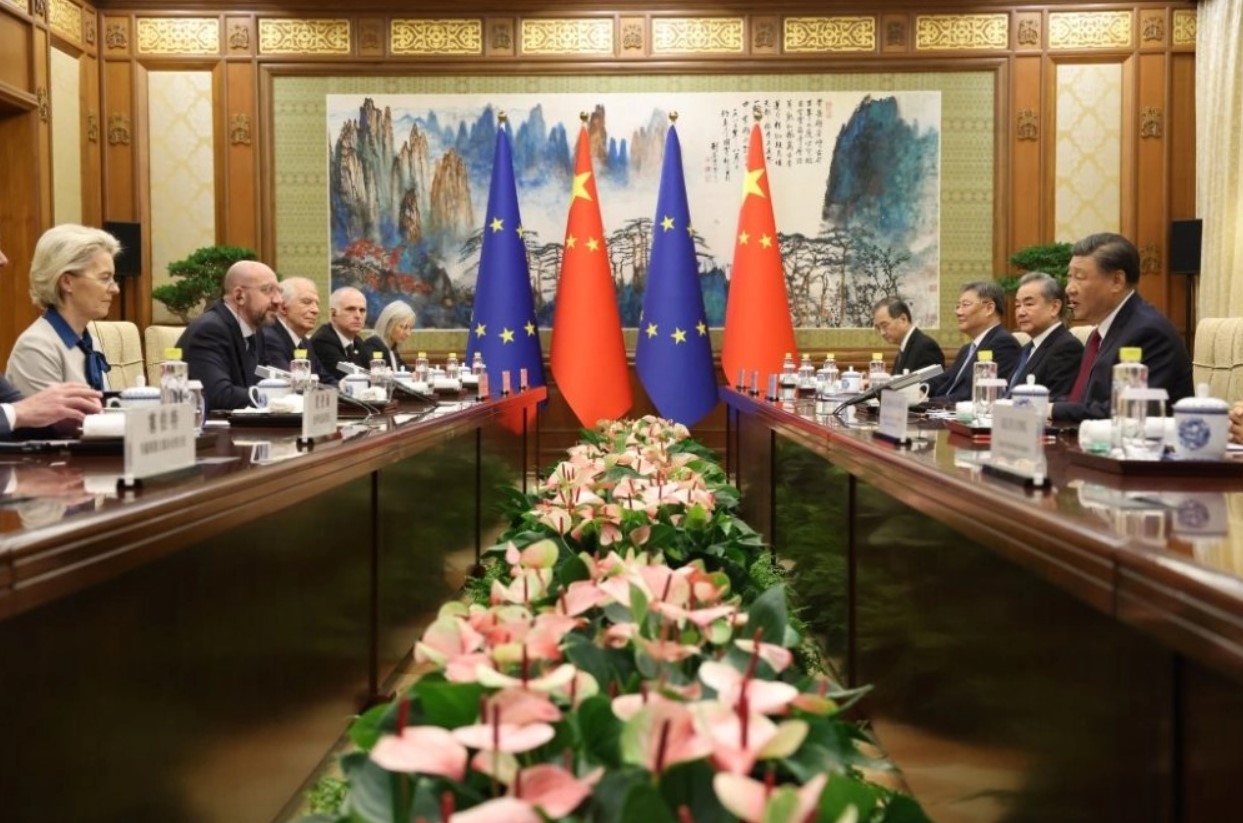

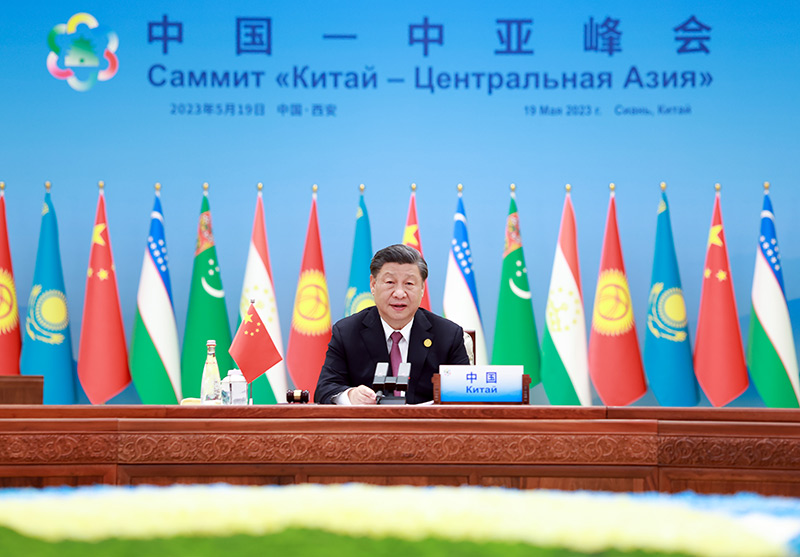

These the breadth of these non-legally binding statements perhaps reflect an organization that continues to struggle to manage multiple concurrent challenges and has yet to find fully coherent responses to any of them. There is intensifying major power competition between the United States and People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia, which creates increasing pressure on ASEAN. Even as the PRC is an important trade and investment partner, its actions challenge the territorial claims of several maritime ASEAN members while its dam projects disrupt ecosystems and livelihoods for mainland ones downstream along the Mekong. The grouping remains unable to move civil war-ridden member, Myanmar, toward stability even as it seeks to induct Timor Leste.

Stating Intentions, Articulating Desires

This year’s summit saw the adoption of ten separate statements on various aspects of cooperation ranging from community-building and the countering the trafficking of persons to electronic payments, electric vehicle infrastructure, and capacity-building. The main Chair’s statement was a wide-ranging, 25- page, 125 paragraph document, covering an intra- and inter-regional cooperation across a variety of domains as well as regional and international developments of concern to ASEAN. The Chair’s statement also included separate sections on perennial maritime issues, the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP) and the grouping’s approach to the ongoing, tragic civil war in Myanmar. If anything, these documents point to areas of relative interest for the grouping.

Standing out from the multiple positions on basic infrastructure and commercial exchanges is the relative emphasis on ASEAN’s interpretation of developments on the Indo-Pacific, the AOIP. Located relatively early in the statement, the relevant section of the Chair Statement, of course, included the expected declaratory language on promoting economic cooperation and sustainability in line with this year’s summit theme of making ASEAN an “Epicentrum of growth.” However, the section also raised issues ASEAN engagement with the Pacific Island Forum (PIF) and Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) as well as the defense and security cooperation thorough the ASEAN Defence Minister Meeting framework. Such outreach suggests an ASEAN desire to interpret the Indo-Pacific to avoid a complete definition of the region by the United States, its friends, and allies in ways that could create more friction with the PRC, something ASEAN members generally hope to avoid.

The statement spent several paragraphs toward the end discussing efforts to move forward with the PRC on differences regarding the South China Sea, including progress over an agreement over the Conduct of Parties. Ostensibly, a binding arrangement governing the behavior of vessels on, over, and under the disputed South China Sea can provide grounds to reduce friction, avoid miscalculation, and avert accidents. Yet, differences over the degree to which major actors such as the PRC may allow themselves to be bound by any agreement and the roles of non-littoral states that regularly use the South China Sea, including for military cooperation with littoral states, remain difficult to resolve. ASEAN members also wish to avoid being blamed for obstructionism, even as they cannot agree on a shared approach. The language and structure of the statement gives some impression of progress, whether that is the case or not.

Another area of note is the relative limited mention of Myanmar and ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus with the Myanmar military. Initially developed to move Myanmar back toward stability and some sort of accommodation among rival groups following the February 1, 2021, coup in the country, the Five-Point Consensus seems to have limited if any effect in achieving its goals. The Five-Point Consensus underlines ASEAN’s unwillingness and inability to apply leverage on the various groups in Myanmar, especially the military. Consequently, Myanmar is still mired in civil war and facing a worsening humanitarian crisis brought about by the widespread use of violence toward civilians by the military, now exacerbated by a massive cyclone that hit the country around the time of the ASEAN summit. There is also a rise the numbers of displaced persons and a spike in heroin production resulting from the unrest. ASEAN’s relative quiescence highlights the fact that Myanmar's dire situation clearly demonstrates ASEAN’s limitations as a regional group.

An Absence of Political Will

Despite the many concerns articulated by ASEAN and its members over the course of the 2023 summit, how they intend to achieve these declaratory goals is unclear. Objectives mentioned in statements are not binding and there is no commitment to dedicate necessary resources. More concrete next steps tend to be voluntary and somewhat tentative. Such conditions reasonably raise questions about whether the grouping and its members have the political will to achieve their stated goals, or whether the lofty aims discussed at this year’s summit are mere wishes, much like similar statements issued in previous years. Even on the shared desire for “ASEAN Centrality,” the summit leaves unclear what the grouping and its members intend to do to ensure that other actors consistently engage ASEAN on substantive matters and use it as a meaningful platform for promoting cooperation.

Paradoxically, Southeast Asia and perhaps East Asia more broadly could benefit most from ASEAN initiative and true centrality at this moment of intensifying U.S.-PRC competition. By negotiating collectively, the grouping can help to mitigate friction over such areas as behavior in the maritime space or the management of dams and water along major rivers in the region, for example. ASEAN can and deserves to play a more effective role in convening discussions over range of issues, including those that may have some level of political sensitivity. A combination of collective and coordination challenges as well as the uncertainties of political transition in ASEAN members such as Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and to some degree the Philippines and Indonesia means less substantive attention and willingness to spend political capital. Such conditions trap ASEAN and its members into a position where declaratory statements dominate over any realistic ability to act.

(Ja Ian Chong is Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, National University of Singapore.)