Australia-China Relations and the Indo-Pacific Under a New Australian Government

How effectively the Labor government addresses a more confident China in the region will be down to how deftly it is able to balance an ever more ambitious Beijing prone to moving the goalposts. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Australia-China Relations and the Indo-Pacific Under a New Australian Government

By Jennifer Y.J. Hsu

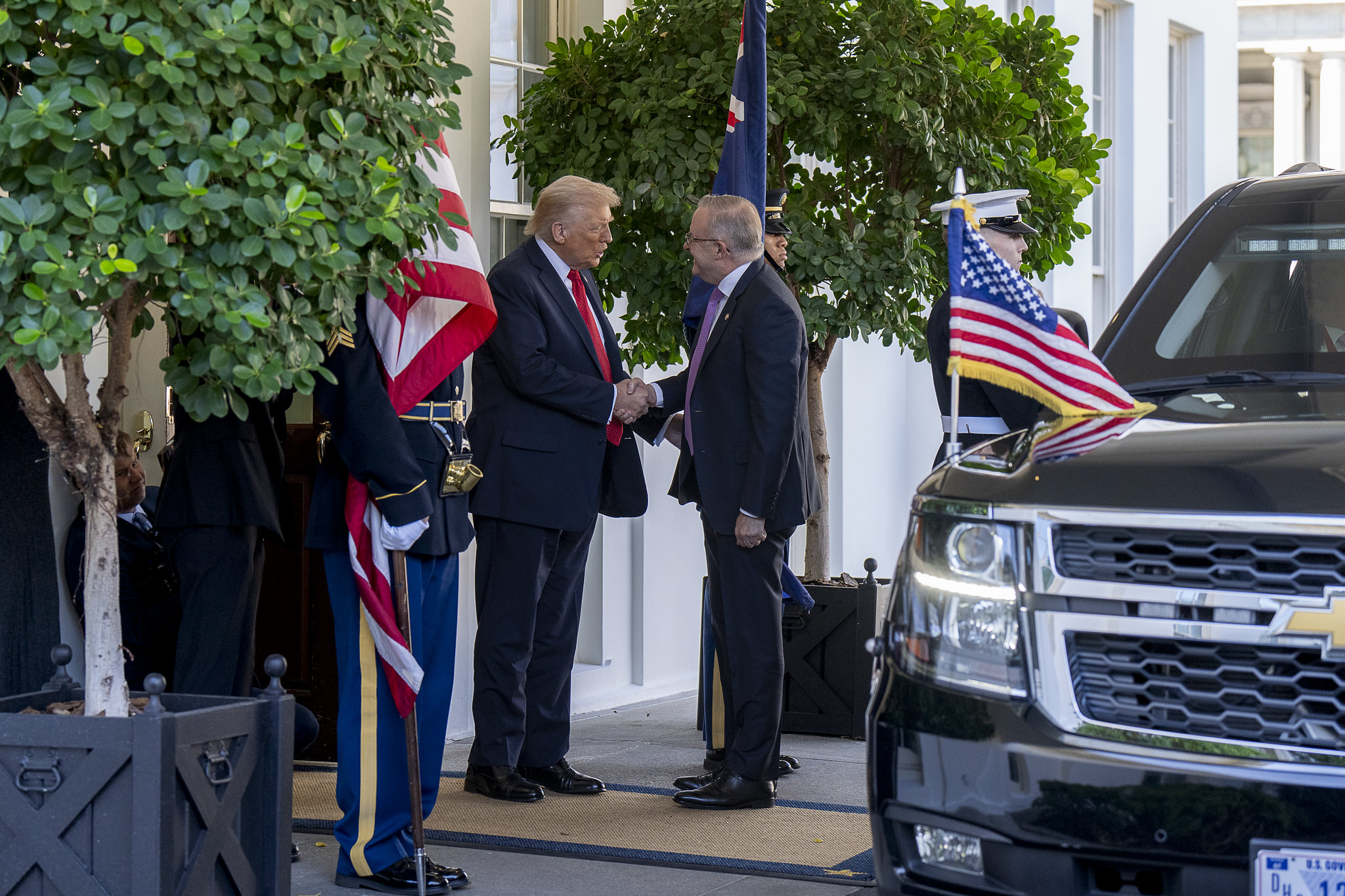

On May 21, Australians elected a new government, ending nearly a decade of Liberal-National rule. There was little time for Anthony Albanese, the newly minted Prime Minister, to bask in a Labor victory. Barely off the campaign trail and just hours after being sworn in, he and Foreign Minister Penny Wong were on a plane to Tokyo for the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) meeting, held with partners Japan, India and the U.S.

Before the election, the Coalition and Labor were essentially in lockstep with one another on key national security issues. There has been bipartisan support for many of the substantial shifts in this policy area over the past few years, including recent announcements on defense and national security, which were broadly seen as motivated by China. This bipartisanship is echoed by the new Shadow Foreign Minister Simon Birmingham.

China is never far from this picture.

Beijing has the ability to stir domestic politics, and Australia has allowed itself to become fixated on China. The Quad and AUKUS – the trilateral security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States – are primarily centered on deterring China militarily. However, security is only a part of the regional picture. Will a Labor government fundamentally shift Canberra’s policy towards Australia-China relations, AUKUS, the Quad, the Indo-Pacific and China/Taiwan? While Anthony Albanese and his government are still in the honeymoon period, and it is perhaps too early to tell, the past month does indicate a change in priorities and policy implementation.

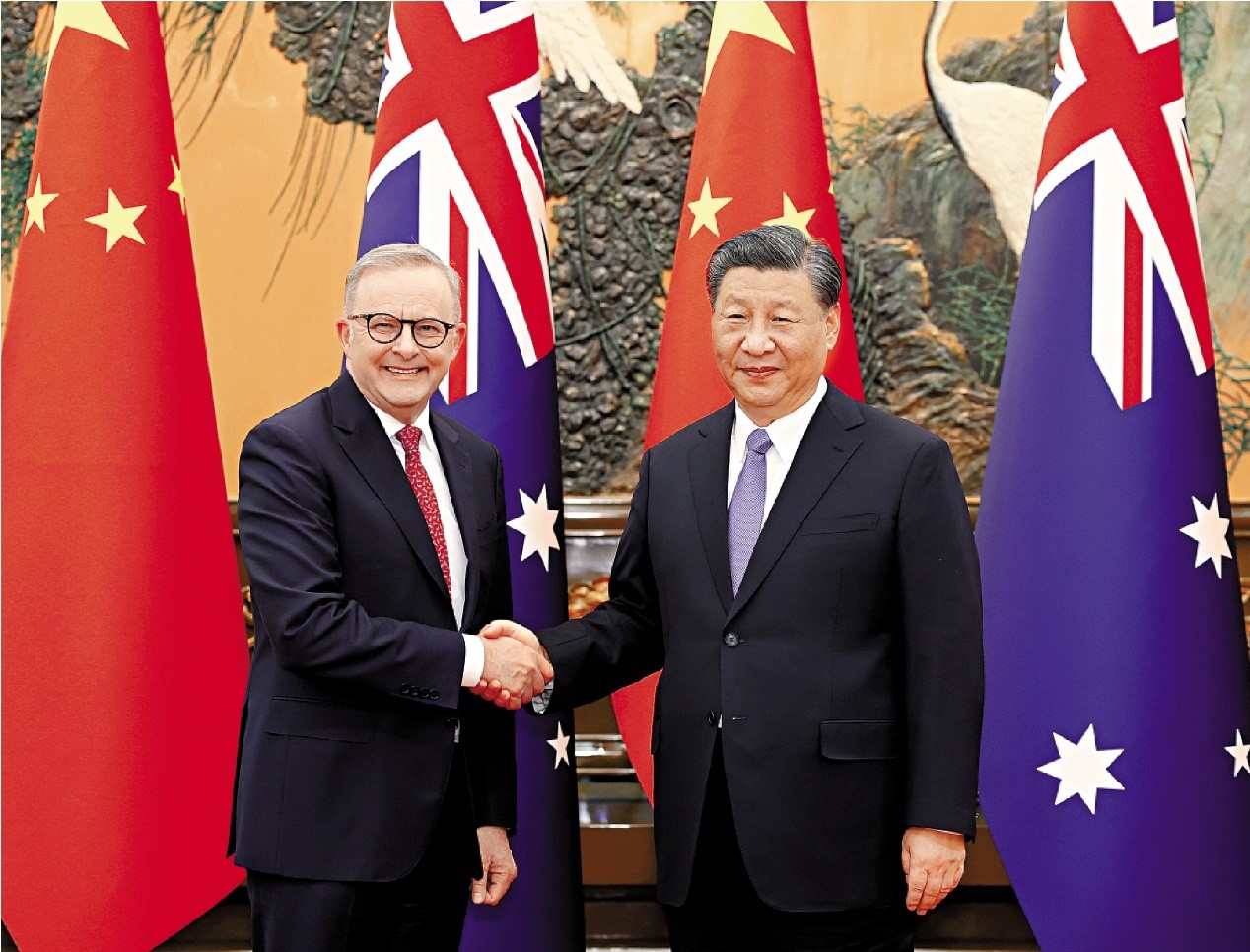

Prospects for Bilateral Relations

After China imposed A$20 billion worth of sanctions on Australian exports and three years of diplomatic freeze between the two countries, there may be a few signs of a thaw. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang sent a congratulatory message to Albanese in the days after his election win, and China’s ambassador to Canberra, Xiao Qian, has indicated the desire to work together to put bilateral relations “back on the right track.” However, despite these promising overtures, Australia’s defense department released a statement on June 5 which revealed that one of its routine maritime surveillance aircraft had been intercepted in a “dangerous act” by a Chinese J-16 aircraft in international airspace over the South China Sea. The interception suggests Beijing’s goodwill is limited, evident in its decision to rebuff Canberra’s demand to drop trade sanctions.

Nonetheless, the recent meeting between Australian Minister for Defense Richard Marles, and his Chinese counterpart, Wei Fenghe, in Singapore brings some hope, albeit with low expectations. Marles noted the complexity of the relationship and the importance of the “critical first step” in re-establishing high-level dialogue. Both sides outlined a list of complaints against each other with no concessions made and no initiatives proposed. Differences remained unresolved, though heard. A reset in bilateral relations is unlikely.

Instead, Australia must manage its expectations. China is demonstrating its right to operate its forces in the region and has its own grievances against Australia. The new government should well and truly do away with the notion of trying to constrain or even neutralize China’s ambition in this space.

China’s Presence in the Indo-Pacific

During Australia’s election campaign, China’s assertion of its right to operate in the Indo-Pacific was in full demonstration. In April, Beijing confirmed it had signed a minimum five-year security agreement with Solomon Islands. The deal is regarded as a major blow to Australia’s strategic position and its self-perception as the premier security partner to countries in the Southwest Pacific. The agreement caused alarm and anxiety not just for the Australians but for the Americans as well. U.S. President Joe Biden hastily dispatched National Security Council Indo-Pacific Coordinator Kurt Campbell to the Solomon Islands to meet with Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, aiming to thwart the deal that had been signed between Honiara and Beijing. Traditionally, Washington has delegated the security of the Southwest Pacific to Australia to “lead” within the bilateral military alliance. The latest security arrangement has been described by observers as an “epic fail” for Australia’s foreign policy.

The deal makes Beijing’s strategic intent in the Indo-Pacific even clearer, which is of little comfort to Australian policymakers. The new Labor government has responded in kind with Foreign Minister Wong traveling twice to the Pacific since coming into office, chasing the coat tails of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s 10-day trip across the region. Wong has committed Australia to assist Pacific Island nations address climate change – a firm acknowledgement of the existential threat to the region and a different stance to that of the previous government. The new leadership in Canberra is seeking to shore up its credentials and reaffirm to the countries of the Pacific that Australia is a “partner of choice” and one that can be trusted.

Australia cannot keep China out of the Indo-Pacific, nor prevent it from making further inroads into the region. While both Fiji and Papua New Guinea (PNG) have publicly weighed in against the China-Solomon Islands deal, member states of the Pacific Islands Forum – of which Fiji and PNG are part – are not always in agreement on key issues, such as the bitter contest over the Forum’s leadership.

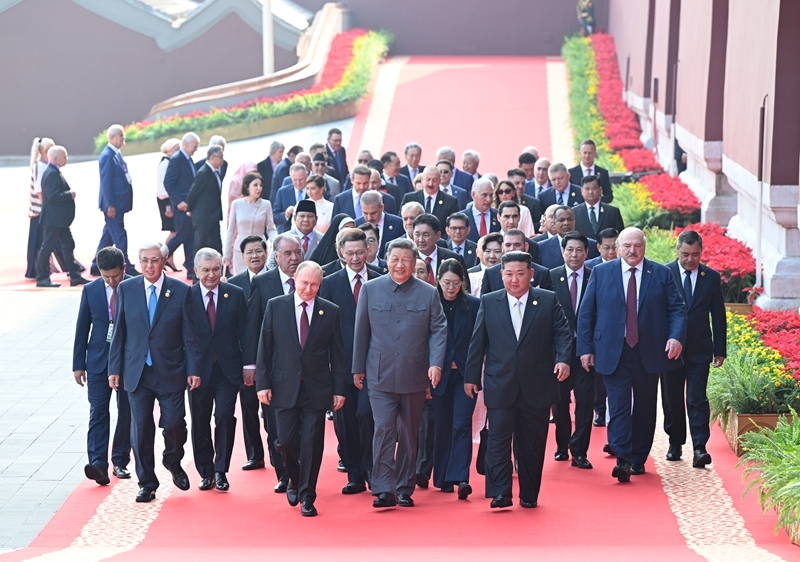

Beyond Partnerships

In the context of a more active China in the region, Australia’s calculation under the former Morrison government was to rejuvenate the Anglosphere. With bipartisan support for AUKUS, Australia is betting on the U.S. to be more present in the Indo-Pacific, but that is only one part of balancing China’s presence. By tethering Australia’s national security and defense capabilities so closely to the U.S., some question Australia’s autonomy in making future assessments within the region.

The rekindling of the Quad is another part of the balancing act. Since the May meeting in Tokyo, Albanese has traveled to Indonesia to strengthen bilateral relations and strategic partnerships. His trip reinforces the Labor government’s plan to prioritize Southeast Asia and ASEAN and provide a platform for multilateralism.

Irrespective of the political party in power, it would seem Australia is committed to the small groupings that are the Quad and AUKUS to hedge against a more assertive China. Canberra’s anxieties about Beijing’s assertiveness were surely confirmed by the latter’s dangerous interception of an RAAF surveillance aircraft in the South China Sea. China’s increasing military pressure on Taiwan is also a source of concern, especially among the Australian public, 52 per cent of whom say a military conflict between the U.S. and China over Taiwan is a critical threat to Australia’s vital interests in the next 10 years. Nonetheless, Albanese has confirmed since coming to power that Australia’s policy on Taiwan has not altered: “[O]ur position is there should be no unilateral change to the status quo.”

How effectively the Labor government addresses a more confident China in the region will be down to how deftly it is able to balance an ever more ambitious Beijing prone to moving the goalposts.

(Dr. Jennifer Y.J. Hsu is a research fellow in the Public Opinion and Foreign Policy Program at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, Australia.)