China’s Naval Projection Sends Important Signals Across the Indo Pacific

The Chinese Naval deployment in February of a powerful task force which partly circumnavigated Australia and conducted live fire exercises off its coast in the Tasman Sea, have sent a visible “shot across the bow” of the Australian government’s rather relaxed approach to defence spending. Picture source: Australian Government Defence, March 9, 2025, Australian Government Defence, https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2025-03-09/peoples-liberation-army-navy-vessels-operating-near-australia.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 15

China’s Naval Projection Sends Important Signals Across the Indo Pacific

By Malcolm Davis

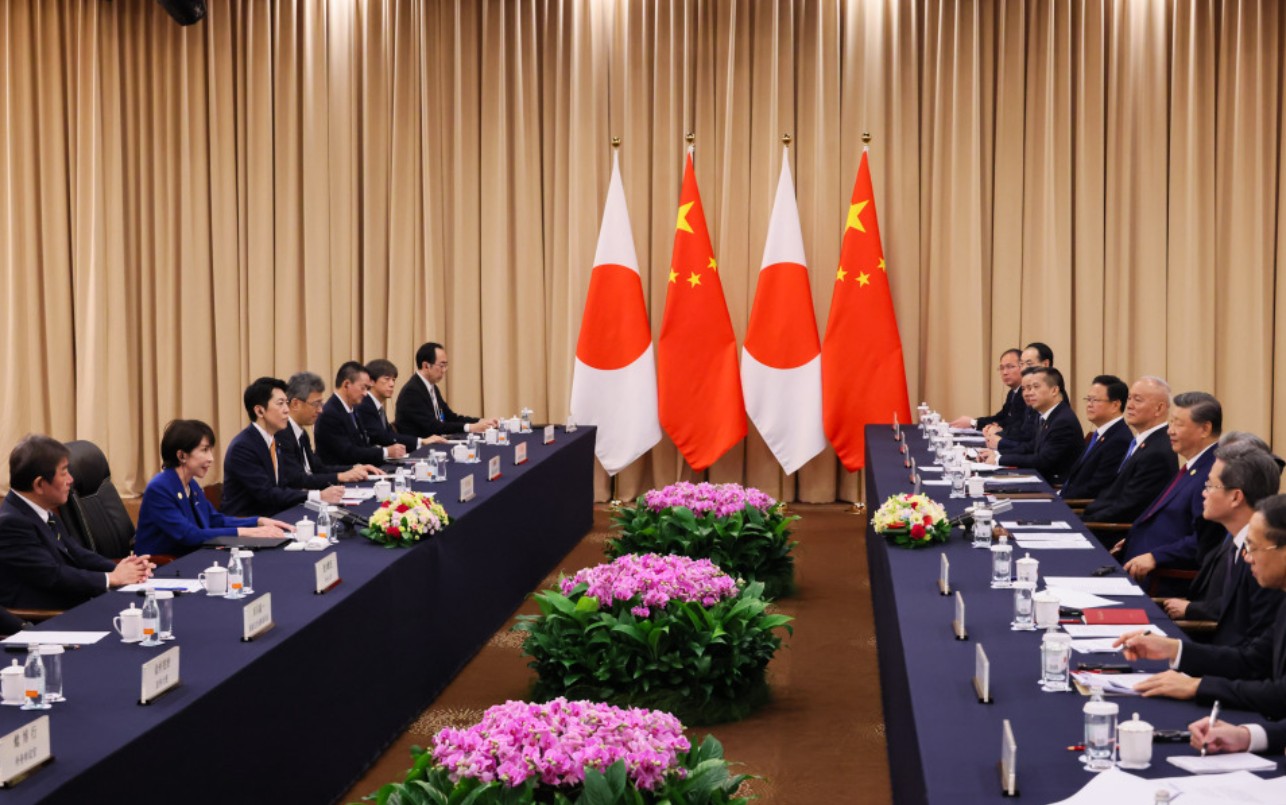

The Chinese Naval deployment in February of a powerful task force, including a Type 055 Renhai-class guided missile cruiser, a Type 054 Jiangkai frigate, and an underway replenishment vessel, which partly circumnavigated Australia and conducted live fire exercises off its coast in the Tasman Sea, have sent a visible “shot across the bow” of the Australian government’s rather relaxed approach to defence spending. The timing is highly significant given that Australia is about to enter a federal election.

This deployment followed a similar one, also with a Type 055 Renhai, to Vanuatu last October, and it occurred at the same time as aggressive Chinese actions against a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft operating in international airspace over the South China Sea.

Australia should expect more visits by vessels from the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) that signal China’s growing maritime power and confidence on the high seas, but it needs to respond with more than just words of concern. The Chinese deployments are a clear signal that Beijing is determined to dominate the high seas and is building the types of naval capabilities to allow it to do so. With that in mind, it is time that Australia put investment in defense capabilities that can be acquired quickly at a higher priority.

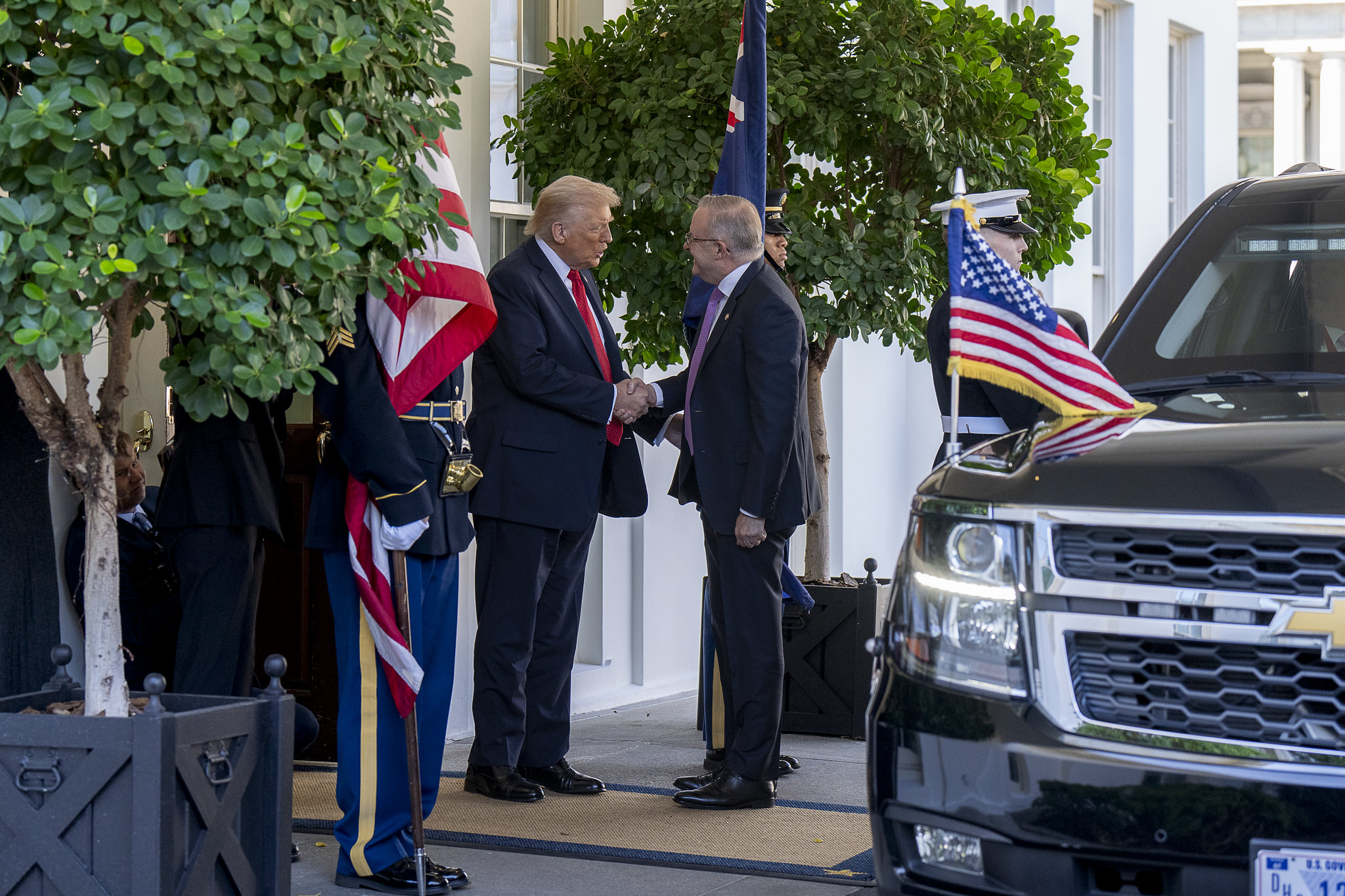

At the same time, the political signals from the Trump administration are clear that the United States will expect Australia to do more, spend more and if necessary, risk more, as part of an enhanced burden sharing to meet the challenge posed by a rising and aggressive China. A failure to respond to these two challenges — one from Beijing and one from Washington, D.C. — will see Australia vulnerable to an emboldened China that is determined to dominate the Indo-Pacific region, and also, at risk of the United States equivocating on key defence arrangements in a future crisis.

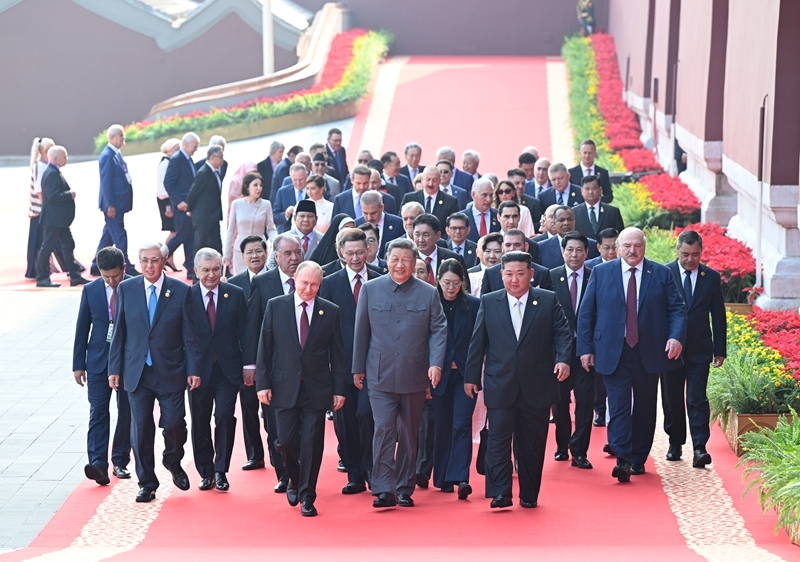

PLA Navy deployment sends clear signals to Canberra and the region

The PLAN task force sailed further south than any previous deployment, and Beijing sent this task force on such a voyage with a specific political and strategic purpose in mind – namely to signal to Canberra, and to the region, that China is a blue water naval power, able to project force and firepower at will to far-flung regions. China is no longer content to remain behind the first island chain but instead will challenge U.S. naval dominance and hold at risk the interests of key U.S. allies when it so desires. Had the region been in a crisis, or even war, this flotilla could potentially have launched long-range missiles against Australian warships at sea or in port, and if equipped with land-attack missiles, struck targets ashore.

The reaction in Australia to China’s deployment has been divided — between naval specialists noting that the Chinese flotilla was operating legally and thus overreacting was an “own goal” that only benefited Beijing, to those speaking from a broader strategic perspective, and warning that China’s deployment highlighted key operational and capability shortcomings within the Australian Defence Force (ADF). In particular, the fact that the Chinese naval flotilla undertook live fire exercises within the Tasman Sea was a point of contention, between those focusing on the legality of such exercises, to those highlighting the specific location and lack of warning for such actions as indicative of strategic signaling.

There was broad consensus of a need to enhance Australia’s naval and maritime surveillance capabilities, especially given the apparent inability of Navy to detect the live-firing exercises, with warning only given by commercial air line pilots in transit across the Tasman.

How can Australia respond to this challenge?

The challenge facing Australia – and other regional actors – is how best to respond to a more assertive PLAN operating out in the blue water in far flung operations well beyond the first or second island chains. For Australia, planning for the expansion of naval capabilities remains a longer-term ambition, with key projects such as SEA 3000 General Purpose Frigates not likely to deliver the first ship until late in this decade, and the first of the Hunter class Future Frigates not due to enter service until perhaps 2033. In the meantime, the Royal Australian Navy continues to suffer from aging vessels such as the Anzac class light frigates, an absence of underway replenishment vessels to sustain ships at sea, and now, concerns about the ability to sustain aging Collins class diesel-electric submarines in service until the first of the Virginia SSNs arrives in 2032 – assuming no delays with that acquisition.

In capability terms, the Royal Australian Navy, and more broadly the ADF, needs to invest in an urgent operational requirement to enhance its ability for sustained maritime surveillance to prevent operational and tactical surprise in the event of a future PLAN deployment into Australian waters. That could be investment in autonomous systems such as drones equipped for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, that could be purchased in significant numbers and at lower cost. Australia’s decision to acquire only four MQ-4C Triton unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) does not really meet this requirement, and the scrapping of defence project AIR 7003 in 2022 that would have seen the acquisition of twelve MQ-9B Sky Guardian UAVs, which could have been acquired quickly, now looks an unwise choice.

Investment in other operational domains, such as space-based intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance satellites, also offers a path to boost Australia’s maritime domain awareness and naval surveillance capabilities. Once again, the government is moving forward at a snail’s pace towards such a capability, with project DEF-799 Phase 2 pushed back into the 2030s for an eventual acquisition of an undefined number of satellites.

Thus, Australia is left vulnerable to Chinese naval operations within its maritime approaches, and inside its economic exclusion zones, that if carried out regularly would weaken Australia’s maritime security. It is certain that Beijing will take advantage of Australia’s gaps in its maritime surveillance and naval capabilities to deploy further flotillas in the future. No can Australia assume the United States under the current administration will necessarily fill the gap. While Australia can and should work with regional partners, such as Japan, South Korea, the Philippines and India, as well as Indonesia, to monitor Chinese naval operations across the Indo-pacific region, and these states need to boost their own surveillance to monitor Chinese naval operations, ultimately it is down to the Australian government recognize a dangerous capability gap and do something about it.

It’s time to get serious about meeting the challenge

The Trump administration’s nominee for Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Elbridge Colby, has indicated to Australia that it should see 3% of GDP as a floor for defense spending. This is correct, and Australia’s government – led by whichever party wins the May 2025 election – should respond positively to his call. Given the growing risk posed by a rising and assertive China, including the growing risk of a crisis across the Taiwan Strait within this decade, it is likely that Australia will need to move well beyond 3% GDP on defense spending if it is to appropriately prepare to respond effectively. It remains uncertain as to whether the next Australian government will recognize this challenge and respond appropriately. But there will be another Chinese naval deployment close to its shores sooner or later, and Canberra cannot ignore the signals from Beijing – or Washington, D.C. – forever.

(Dr. Malcolm Davis is a Senior Analyst in Defence Strategy at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra)