Mr. Albanese Goes to Beijing: What Does It Mean for Australia-China Relations?

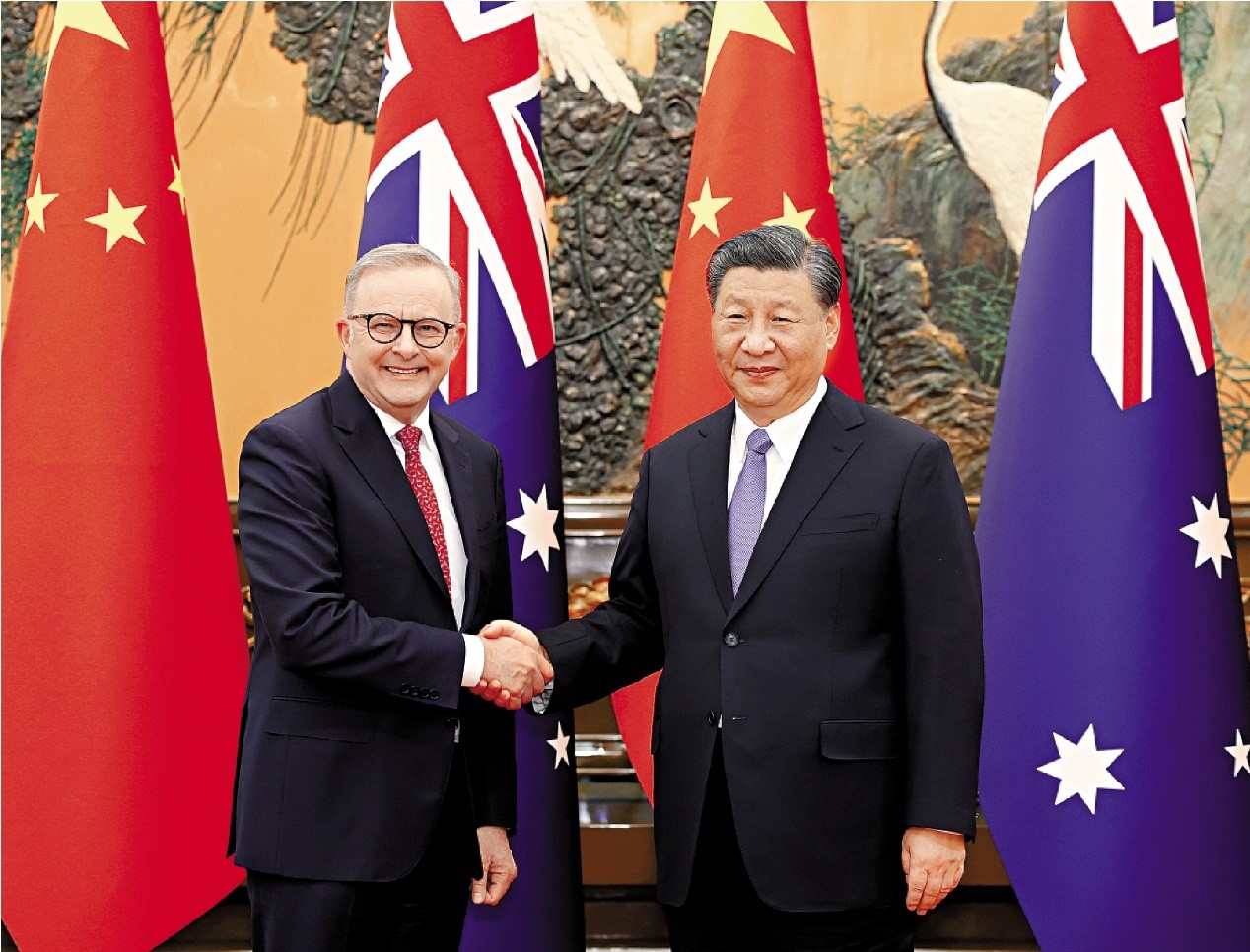

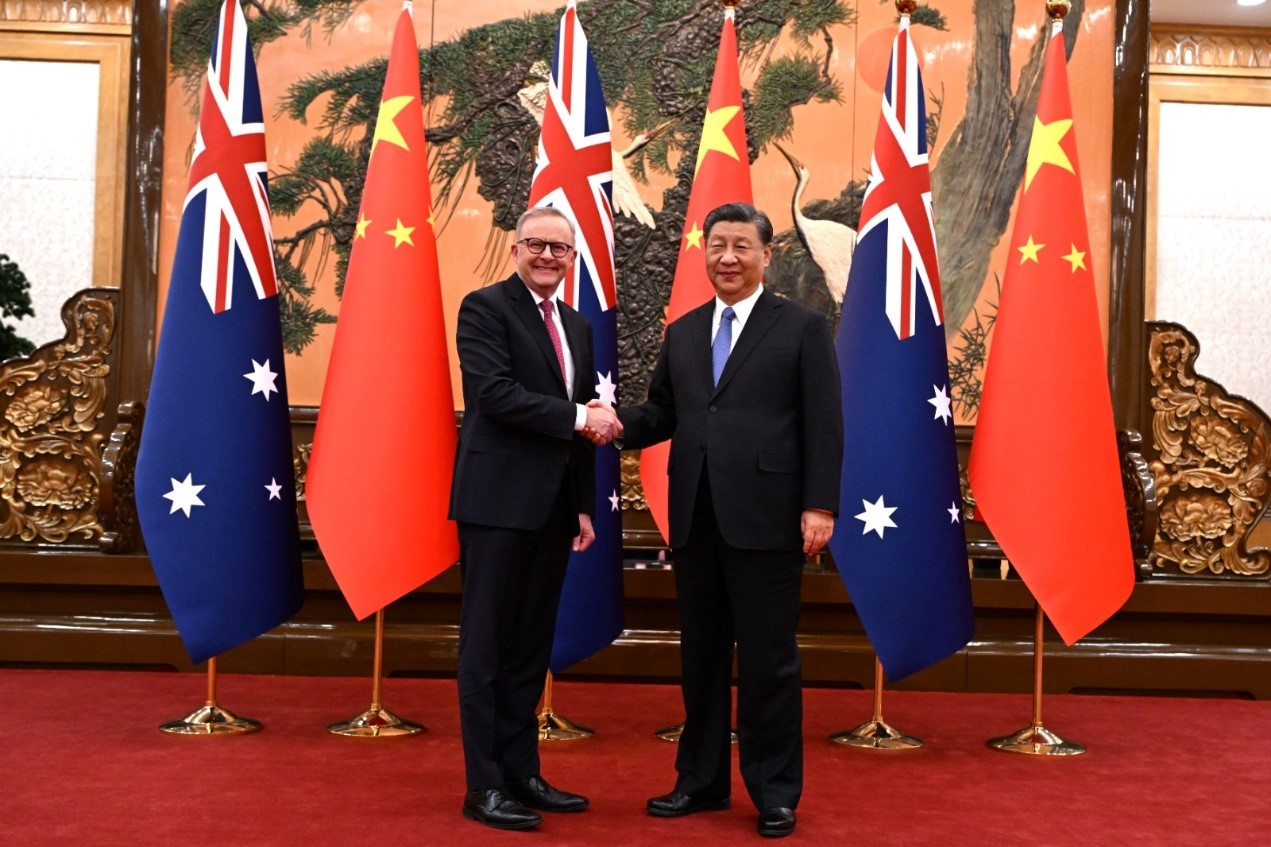

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese visited China from November 4-7 to mark the 50th anniversary of the inaugural visit by a Labor Prime Minister in 1973 and, more concretely, to improve bilateral ties after a four-year hiatus in high-level contacts between the two countries.

Photo source: Xinhua News Agency, November 17, 2023, HKTKWW, https://www.tkww.hk/epaper/view/newsDetail/1721604051927437312.html.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 70

Mr. Albanese Goes to Beijing: What Does It Mean for Australia-China Relations?

By John Fitzgerald

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese visited China from November 4-7 to mark the 50th anniversary of the inaugural visit by a Labor Prime Minister in 1973 and, more concretely, to improve bilateral ties after a four-year hiatus in high-level contacts between the two countries. Under the previous Liberal/National Party coalition government (2013-2022), relations had deteriorated to the point where Beijing imposed a virtual freeze on high-level government communications and, starting in 2020, a barrage of trade tariffs and prohibitions affecting Australian exports valued at around US$15 billion. Over a year of intensive negotiations ahead of Albanese’s visit, Beijing began to lift its punishing trade bans and resume ministerial-level dialogues, and at the time of the visit freed detained Australian journalist Cheng Lei.

What changed to elicit such a positive set of responses from Beijing?

At the Australian end, not a great deal. The Albanese government’s approach to China differed little from that of its predecessor, apart from modifying its diplomatic tone and reducing public advocacy around the challenges China presents to liberal democracies generally. A simple change of government helped. In one sense Beijing’s invitation to Albanese was a message of congratulations to the historically pro-China Labor Party on winning Australia’s national elections in May 2022. If Beijing thought a change of government was needed to mend the break, then clearly the Australian side had to do the changing. China does not routinely rotate its party in power.

Albanese went into the federal election promising to “stabilize” relations by restoring trading and government-to-government ties with China while maintaining close engagement with allies and partners, including the controversial AUKUS agreement with the U.K. and U.S. on acquiring nuclear-powered submarines. Given these competing commitments, the Albanese government’s efforts to stabilize relations are best understood not in relation to short-term bilateral trade-offs but against longer term developments in the diplomatic, economic and security environment — some involving Taiwan — on which bilateral relations are playing out.

From the Australian side, it is no exaggeration to say there has been a fundamental shift in the premises underpinning Australia-China relations over the past decade. To be sure, China remains far and away Australia’s largest trading partner, but trade and investment are no longer the primary drivers of Australia’s foreign policy settings, and China is far from the only regional player drawing serious attention in Canberra. The ground underpinning bilateral relations has shifted to the point that short term deals are unlikely to halt the deeper structural trends under way.

Shifting ground

One measure of how far the ground has shifted is Australia’s 2017 foreign policy reset. Another is the range of new diplomatic, security and defense initiatives with neighboring countries flowing from that reset, including relations with Japan, India, the Republic of Korea, and the Philippines.

On foreign policy, the new rationale underpinning relations with China was formalized in the preceding government’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. On China, it noted foreign interference threatening Australia’s sovereignty and security, it expressed concern over competing maritime and territorial claims in the region, and it promoted “resolution of differences through negotiation based on international law.” Above all, it reflected growing concern in Canberra for explicitly upholding what it called the international rules-based order, referring to the postwar institutions and norms centered on the U.N. that were established often at U.S. initiative in the decade following WWII.

With respect to security and defense, the shifting ground of bilateral relations with China was laid out in the preceding government’s 2020 Defense Strategic Update, which identified the changing threat environment in the region and spelled out its implications for Australian defense planning and cooperation. Among other things, the 2020 Update abandoned the long-held assumption that Australia enjoyed the luxury of ten years strategic warning ahead of likely conflict and it anticipated greater likelihood of high-intensity conflict in the near to medium term. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pressed that message home just months before Albanese took office.

Continuity in foreign relations and defence

The incoming Albanese Government quickly confirmed the outgoing government’s recent revisions to Australia’s foreign and defence policies. Speaking to the National Press Club in Canberra in April 2023, Foreign Minister Penny Wong pointed to China militarizing disputed features in the South China Sea; its forcing dangerous encounters in the air and at sea; its firing ballistic missiles over Taiwan into Japan’s exclusive economic zone and practicing strikes and blockades around Taiwan; and more broadly its threat to the rules, standards, and norms that long brought relative peace and prosperity to the region. The Albanese government would harness all elements of national power, she said, to defuse these challenges and help shape a region that reflected Australia’s national interests, in sum a region “that operates by rules, standards and norms — where a larger country does not determine the fate of a smaller country; where each country can pursue its own aspirations, its own prosperity.” To convey the message abroad, Wong visited over thirty countries in her first year as foreign minister, including all Pacific Island Forum members and several Southeast Asian capitals.

The Albanese government also confirmed the outgoing government’s assessment of the current threat environment. Three months into office, Albanese and his Defense Minister Richard Marles announced a comprehensive defense strategic review that would pick up where the previous government’s 2020 Defense Update left off. In the words of Marles, Australia now faced the ‘’toughest strategic environment the country has encountered in over 70 years.” The resulting Defense Strategic Review 2023 (DSR) is the most comprehensive of its kind in almost four decades. The DSR assumes a decline in U.S. military pre-eminence relative to China but does not anticipate a declining role for America in the Indo-Pacific. Instead, it casts the U.S. in a new role as cornerstone of an integrated regional deterrence strategy in which Australia needed to play a greater role alongside other regional allies and partners.

Consistent with that strategic vision, Canberra accelerated defense cooperation with Tokyo through a 2022 joint declaration on security cooperation and reciprocal access agreement, and a series of joint defense exercises, along with combined strategy and planning sessions at trilateral Japan-U.S.-Australia defense ministers’ meetings. A range of cooperative defense arrangements were also initiated with the Republic of Korea, India, and ASEAN countries, most notably the Philippines. In August 2023, just three months ahead of Albanese’s visit to China, the Australian and Philippines governments elevated their relations to a “strategic partnership” and Australia sent 1,200 troops to take part in a joint military exercise with the Philippines simulating the recapture of an island occupied by an unnamed hostile power. These moves followed closely on a joint naval exercise off the West coast of the Philippines involving vessels from the Royal Australian Navy, the US Navy and Japan’s Self Defense Force, again on Albanese’s watch.

Diplomatic discontinuity

One concession the Albanese government has made to Beijing relates to diplomacy, in the sense both of not ruffling feathers and of projecting influence abroad. On the one hand, under Albanese Canberra has modified the tone of government communications with China to reduce the risk of offense. On the other, the new government appears to have disavowed the kind of activist diplomacy with third parties concerning China which so enraged Beijing under the previous government.

Starting around 2016, at a time when other nations were barely aware of the challenges of open engagement with China, Australia drew attention to risks arising from Beijing’s interference operations in foreign jurisdictions, its coercive diplomacy, its overseas infrastructure investments and telecommunications equipment in national grids, and to the comprehensive challenge to international law posed by China’s unilateral actions in disputed maritime territories. China’s state-run media branded Australia an“upstart” for its outsized role in bringing these issues to international attention. The Albanese government’s reduced diplomatic advocacy on these issues, and its general change of tone, carry outsize weight in Beijing because they signal its success in putting the pesky Australian “upstart” back in its box.

Missing policy initiatives: Taiwan

Policy continuity includes acts of omission. The Albanese government signaled good will toward China by maintaining the previous government’s position of not taking decisions on Taiwan that could possibly give offense.

Australian inaction is all too familiar to officials in Taiwan who have long hoped Canberra’s growing recognition of the threat China poses to peace and stability in the region would open wider policy space for Australian government initiatives in partnership with Taiwan, specifically with respect to a bilateral a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and Taiwan’s application for membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Influential Australian analysts including Rowan Callick and Ben Herscovic continue to advocate for the FTA and CPTPP, but the Australian government is holding firm against them. Taiwan is an especially sensitive touch point in the recently stabilized relationship with China.

While the Albanese government has shown little appetite for launching new initiatives in bilateral relations with Taiwan, its forward defence posture and its commitment to defence cooperation with regional partners and the U.S. can reliably be read as indicating an ongoing commitment to maintaining peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait and in the East and South China seas. The Albanese government has if anything hardened Australia’s position in support of peace and stability bearing on Taiwan.

(John Fitzgerald is an Emeritus Professor at Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, and Visiting Fellow at National Cheng Chi University on a Ministry of Foreign Affairs Taiwan Fellowship.)