Both Britain and Taiwan share interests: in supporting U.S. strategy, in pushing back against mainland Chinese influence, and in strengthening multilateral security structures. The potential for cooperation is there.

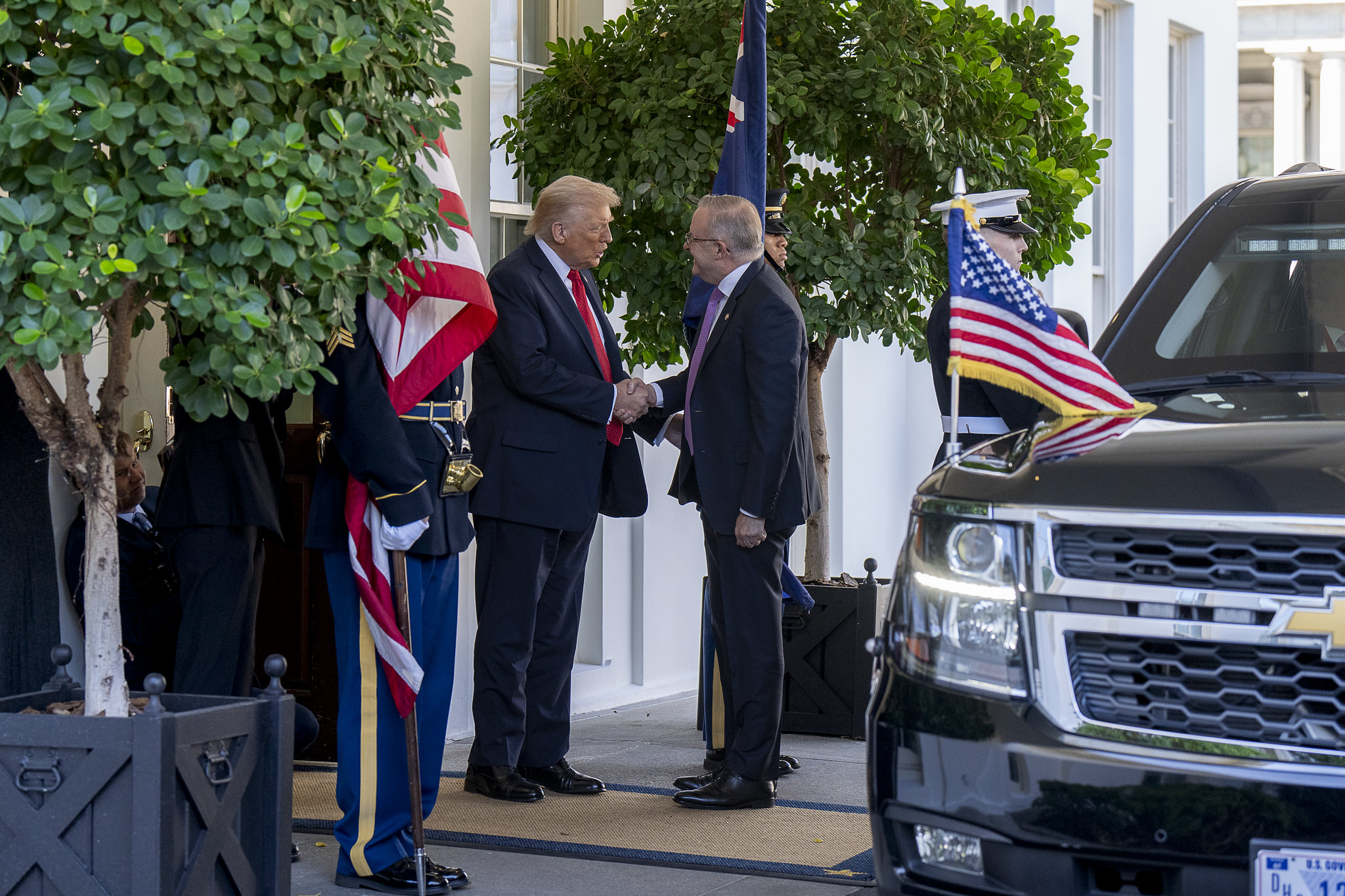

Picture source: Taiwan in the UK 駐英國台北代表處, October 5, 2022, www.facebook.com/Taiwan.in.UK/posts/pfbid02sQ3KvFD8CKK7X1L7LpUjNmb9ENsQXXQNo9kBUeX9Q7NvoMXzUH4H5B1fXkKNYQwil

Can Britain Help Taiwan?

Prospects & Perspectives No. 60 October 17, 2022

By Edward Lucas

After decades of neglect, Taiwan is again fashionable in London. At the de facto Taiwanese embassy national day this year, as last year, British politicians made a point of being photographed with the head of mission, Kelly Wu-Chiao Hsieh. Supporting Taiwan is a cost-free symbolic way for British public figures to show their distance from Chinese authorities.

Part of that picture was the “special invitation” last month to Hsieh to sign the condolence book for the Queen Elizabeth II, along with other fully accredited diplomatic representatives.

Another sign of progress is the Lord Mayor’s Show. This is a large street party organized in the City of London, Britain’s financial district, under the Lord Mayor who plays an important symbolic and ceremonial role in London’s public life. Participants include schools, military units, public services, banks and other institutions.

In 2017 and 2018 Taiwan took part, with a display organized by the Representative Office, EVA Airways and China Airlines, a Taiwanese travel agent, the Taiwan Trade Centre and other Taiwanese businesses. But in 2019, at Beijing’s insistence, Taiwan was excluded from the Lord Mayor’s Show. After a lengthy public and private campaign, an invitation to take part in the 2021 show was issued, but too late for Taiwanese participants to organize proper involvement.

This year’s show does not appear to have any Taiwanese participation. But some signs suggest that the City of London’s timid policy towards China is changing. Another Lord Mayor’s visit to Taipei is under discussion. Such visits took place previously, in 2014 and 2016.

Liz Truss’s government is offering rhetorical support too. Asked about Britain’s stance on defending Taiwan from Chinese attack, the prime minister said “What I’ve been clear about is that all of our allies need to make sure Taiwan is able to defend itself, and that is very, very important.”

But what can we expect in practical terms? The Truss government is in such turmoil that it will have little bandwidth for foreign policy. What energy it does have will be heavily taken up with the war in Ukraine, and in Britain’s commitment to defending NATO allies in Europe, chiefly Estonia.

The British government is keen to show the American administration that it is still a power in the Indo-Pacific region. The centerpiece of Britain’s presence there is naval, with participation in FONOPs (Freedom of Navigation Operations) in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait. That will continue. The AUKUS (Australia, UK U.S.) deal on nuclear submarine technology is important too, though Britain’s involvement in this is easily overstated.

But given the US emphasis on supporting Taiwan, Britain will do what it can to help on that front too. For a start, Greg Hands, the new minister of state for trade policy, should be visiting Taipei before the end of the year. Hands is an able politician who in different times could have expected a more senior job in government. His misfortune was to oppose Brexit in 2016, after which he has held only junior ministerial roles.

Britain’s relations with China are chilly. A new national security document is likely to describe the Beijing regime as an “acute threat,” akin to Russia. There is growing concern about mainland China’s presence in British universities, for example. British higher education institutions are now encouraged to carry out risk assessments of their contacts with foreign governments. The government is encouraging them to close the notorious Confucius institutes, which number around 30 in Britain. Hawkish MPs are trying to involve Taiwan in Mandarin-language teaching instead. This would parallel the efforts of the Overseas Community Affairs Council, which has been setting up Mandarin learning centers in U.S. cities, in tacit competition with Confucius institutes.

The area where Britain can perhaps be of most use right now is in supporting Lithuania’s stance on Taiwan.

The Baltic state, acting more out of principle than from any pragmatic considerations, invited Taiwan to open an office in the capital Vilnius. This mission, although not a full embassy, operates as the Taiwan Representative Office, rather than under the “Taipei” label used in every other European country except the Holy See, which still has diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Many China hawks in Britain and elsewhere hoped that Lithuania’s example would be followed across the region. Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Romania were all potentially interested in taking similar steps. All are dissatisfied with China's 17+1 framework for cooperation with eastern Europe. All are strongly Atlanticist and eager to help the United States in any way they can.

However Lithuania’s experience has been disappointing. Promises of trade and investment ties with Taiwan have not, so far, materialized. Lithuanian exports to China have been blocked. Worse, even European Union exports with Lithuanian components have encountered obstacles. German companies have told the Vilnius authorities the Taiwan policy is hurting the chances of future investments.

Lithuania is complaining via the World Trade Organization about its treatment by the Chinese authorities. Lithuanian officials are disappointed with the lack of support they have received from the European Union and from the United States. They are hoping that Britain, which in the post-Brexit era has developed its own substantial presence at the WTO, will be willing to help.

Another potential British role is in the Three Seas Initiative. This is a western-backed rival to the Beijing-run 17+1 (now 14+1 as several of the original members have pulled out). The TSI aims to improve connectivity in the countries between the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and the Adriatic. Founded more than a decade ago, it has struggled to attract heavyweight funding and diplomatic backing. But as a way of pushing back against Chinese influence in the region, it has potential. British officials would be pleased if Taiwan would also take part, building on successful Taiwanese involvement in the London-based European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Both Britain and Taiwan share interests: in supporting U.S. strategy, in pushing back against mainland Chinese influence, and in strengthening multilateral security structures. The potential for cooperation is there. The problem is that the British government is so beset with economic woes, political challenges and other distractions that it is hard to see scope for innovation and consistency in foreign policy.

(Edward Lucas is a Non-resident Senior Fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA).