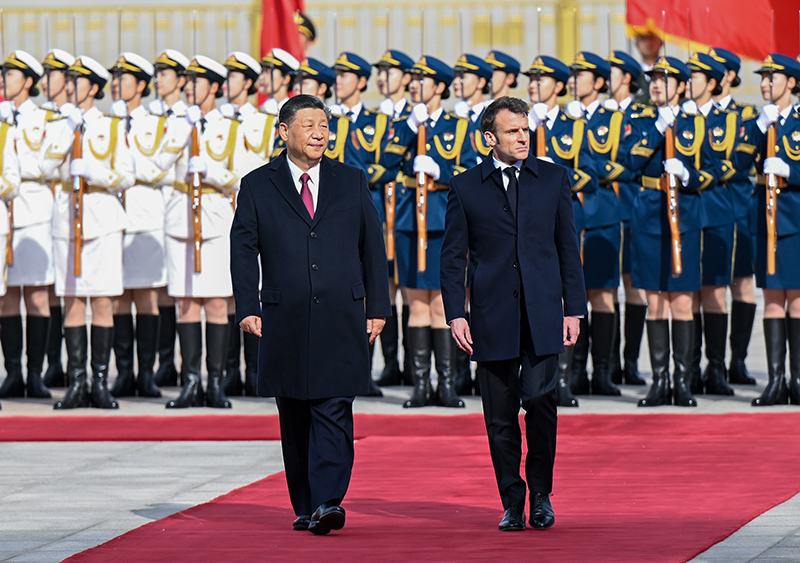

Chinese interest in Estonia, particularly towards its strategic infrastructure, predates the public security assessments of the intelligence services. China has been interested in developing ports and airports in the Nordic-Baltic region for decades. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Prospects & Perspectives 2022 No. 25

Estonia’s Evolving Threat Perception of China

By Frank Jüris

April 28, 2022

According to the Estonian Internal Security Service (KAPO), Chinese interest in Estonia increased after Estonia’s accession to NATO and the EU in 2004. Not until 2018, however, was China for the first time mentioned in both KAPO’s and Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service’s (EFIS) annual — and traditionally Russia-heavy — reports. Today, China deserves its own chapter in the EFIS report, and KAPO has caught two citizens cooperating with Chinese military intelligence, one of whom, marine scientist Tarmo Kõuts, had both a NATO and Estonia security clearance. Kõuts has been convicted, which established a precedent not only in Estonia but, to a certain extent, in Europe as well, where similar convictions are, in contrast with the U.S., rare and often not made public.

Chinese interest in Estonia, particularly towards its strategic infrastructure, predates the public security assessments of the intelligence services, but not the threat perception. China has been interested in developing ports and airports in the Nordic-Baltic region for decades — with limited success thus far, due to concerns also expressed by the Estonian government over the feasibility, impact on environment, and national security.

With China’s increasingly assertive foreign policy, discussions about China’s rise and the potential threats associated with it have moved from government corridors to the public space. For a long time, public discussions about China were dominated by talks about economic opportunities: namely access to the Chinese market and attracting Chinese investments, which was particularly important for Estonia after worsening relations with Russia in 2007 and the global economic crisis that followed in 2008.

Thus far, despite Estonia’s participation in the 16+1 grouping since its establishment in 2012, the opportunities have not yet materialized. For Estonia, China therefore remains an insignificant economic partner. Instead, Estonia has witnessed the rise of Chinese influence, as reported by the Estonian intelligence services. The narratives in China and Estonia have to a certain extent been harmonized, as a pre-condition for economic success is the avoidance of any criticism of China and what it regards as its “core interests.” When Estonia downgraded its participation at the 16+1 virtual forum to foreign minister level in 2021, the response in Estonian media was to ask how China would punish us. The memory of the Dalai Lama’s visit in 2011, and the denied access of Estonian dairy products to the Chinese market, still linger in the public discourse; in reality, however, both the sticks and carrots remain largely imaginary.

The long-lasting narrative supportive of Chinese interests in Estonia has been that in order to have success in China, it is necessary to establish personal relations at the central and local levels of government, in the private sector and academia over a long period of time. People targeted by China often lack the necessary language skills and understanding of the Chinese political system, and in general are unaccustomed to thinking in national security terms. All of this makes them vulnerable targets of Chinese influence, proponents of China’s interest and silencers of any criticism of China — often without them being conscious that this is what they are doing.

The issue of China’s growing influence came to the foreground when three former Estonian ministers launched lobbying efforts to assure Chinese company Huawei’s involvement in the construction of Estonia's 5G network, which culminated with one minister attending a close-door meeting in parliament in February 2020 dedicated to discussing the security risks associated with Huawei. Currently, the issue is off the table, thanks largely to an amendment to electronic communication law, whereby software and hardware used in 5G networks must be risk-free by 2024.

In retrospect, 2017 should already have been an eye-opening moment to tilt the discussion from economic opportunities to security threats, when China and Russia held a joint naval exercise in the Baltic Sea. Also the same year, CITIC Telecom, which belongs to the CITIC Group, acquired Dutch company Linxtelecom and with it the backbone of Estonian Internet infrastructure including the 470km-long fiber optic cable in the Baltic Sea and Tallinn Internet Exchange Point. In the latter discussions over Huawei’s involvement in the construction of the 5G network in Estonia, the argument of Huawei’s independence from the Chinese party-state was plausible for people unfamiliar with the Chinese political and economic systems and the 2017 intelligence law that requires legal and natural entities to cooperate with the Chinese intelligence services. The same argument could not have been upheld in the defense of the CITIC Group, which was described by Rand corporation already in 2006 as the front company of the PLA, if there was any media attention or public discussion of it at the time. To make things even worse, at the end of 2017, Estonia signed three Belt and Road Initiative-related MOUs, among them one pertaining to the Digital Silk Road.

The blame should not be entirely on Estonia, which according to the intelligence service’s annual reports is still ahead of the curve in addressing the China threat and is known for working on an investment-screening mechanism to protect its strategic infrastructure and technology sector. Even if the investment-screening mechanism was intact, how could it have stopped a Dutch company selling its assets to a PLA front company, which likely had a negative impact on the security of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn, which, among other allies, the Dutch government funds and staffs?

How can similar mistakes be avoided in future? For instance, Estonia hosts the only European rare earth processing plant Silmet. This plant is run by Canada-listed Neo Performance Materials. Hypothetically speaking, if China were to strengthen its monopoly on rare earths by acquiring Silmet from the Canadian company, how could Estonia, Europe and to a certain extent the U.S., whose all-supply chain resilience is at stake, stop it from taking place?

(Frank Jüris is Research Fellow of the Estonian Foreign Policy Institute at the ICDS)