The new Czech government still struggles with the lingering power of the president and special business interest. Picture source: Czech Republic, November 8, 2021, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:L%C3%ADdrov%C3%A9_s_koali%C4%8Dn%C3%AD_smlouvou_2021.jpg

Prospects & Perspectives 2022 No. 12

The New Czech Policy Towards China: A Discreet Overhaul

By Martin Hála

March 3, 2022

Last year’s elections rewrote the political landscape in the Czech Republic. After eight years in opposition, the mostly center-right, pro-Western parties swung back with a comfortable majority of 108 seats in the 200-member Parliament. This has opened the way for a long-awaited “review” of the Czech foreign policy orientation that had been sliding towards Beijing (and until recently, Moscow) under the influence of Czech President Miloš Zeman, elected in early 2013.

A special president and special interests

In the Czech Republic parliamentary system, the role of the president is meant to be largely symbolic. Foreign policy is within the government’s purview, with purely representative role for the head of state. The constitution is, however, rather vague and Zeman has proven eager to stretch it. He was able to get away with it because until the October elections, he had been facing a series of weak governments he could manipulate with relative ease. The first one, in 2013, he even created himself and kept it in office without the required parliamentary vote of confidence for almost a year. By stretching the limits of his constitutional powers against a series of feeble cabinets, he was able to effectively run the country’s China policy for eight long years.

Before becoming president in 2013, Zeman had had a history of pro-Kremlin contacts, but not Chinese. His turn towards Beijing shortly after assuming office was rather unexpected. A major factor seems to have been the efforts of the richest Czech financial conglomerate, the PPF, and its consumer loan subsidiary Home Credit (HC) to extend its commercial license for Tianjin to cover all of China. The chief lobbyist for the company duly became Zeman’s China adviser in 2013. In 2014, HC was indeed awarded the coveted nation-wide license in China — and a year later, Zeman publicly thanked Sun Chunlan, the Tianjin Party Secretary who meanwhile had moved to head the United Front Work Department, for facilitating the license.

Apart from Zeman, the turn towards Beijing had been supported by the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD), the major partner in the governing coalition in 2014-2017, and a minor one in 2017-2021. It was also assisted by the Czech Communists (KSČM) who had become a tacit partner in the post-2017 coalition. Both ČSSD and KSČM were voted out in the October 2021 elections. At the same time, Zeman’s health deteriorated rapidly in late 2021.

The pro-Beijing political forces have been much weakened as a result. However, the business interest behind them, namely PPF and HC, remains strong despite the tragic death of the company’s founder and majority owner, Petr Kellner, in a helicopter crash in March 2021. Since its emergence in the privatization process in the 1990s, the company has wielded political influence in the Czech Republic across the political spectrum. It continues to be felt even after last Fall’s political changes. Together with the fading but lingering power of the president, this has somewhat blunted the new government’s resolve to confront Beijing.

All toe the premier’s line

The opposition was able to prevail in October 2021 by uniting in two broad-based coalitions comprising five “democratic” (as opposed to “populist”) parties covering a broad-range political spectrum. Despite the professed unity of purpose, there are substantial differences among the parties, and sometimes within them, on specific issues, including on China.

The one party most critical of the previous pro-Beijing policy is the Pirates who got to field the foreign minister in the new government, Jan Lipavský, known for his uncompromising stance on China (as an MP in the previous parliament, he served as the Czech Republic’s co-chair of the Inter-parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC).

His nomination was naturally a red flag for the pro-Beijing Zeman, who vowed to block it. The Constitution gives him no such power, but he had succeeded in ousting candidates, and even sitting ministers, in previous governments. This time, the Prime Minister-elect, Petr Fiala, stood his ground, apparently threatening to take Zeman to the Constitutional Court. The President relented, but only after securing a pledge from Fiala that he would make sure Lipavský as the foreign minister “follows the government’s line” on foreign policy.

Prime Minister Fiala’s party, the ODS, has a long and convoluted history with influential members often taking contradictory positions, in particular on foreign policy. During one of its stints in opposition, its shadow foreign minister in 1998–2006 was Jan Zahradil, the one-time head of the now effectively defunct China Friendship Group in the European Parliament. His influence seems to have waned, but he is known to be close to some of Fiala’s foreign policy advisors, formal and informal.

Fiala’s advisers mostly hail from the ODS “college” called CEVRO, an institute sponsored by PPF, the company that had backed the Czech Republic’s turn towards China after Zeman assumed the presidency in 2013. Some of these advisers also have long-running personal links to PPF’s top lobbyists.

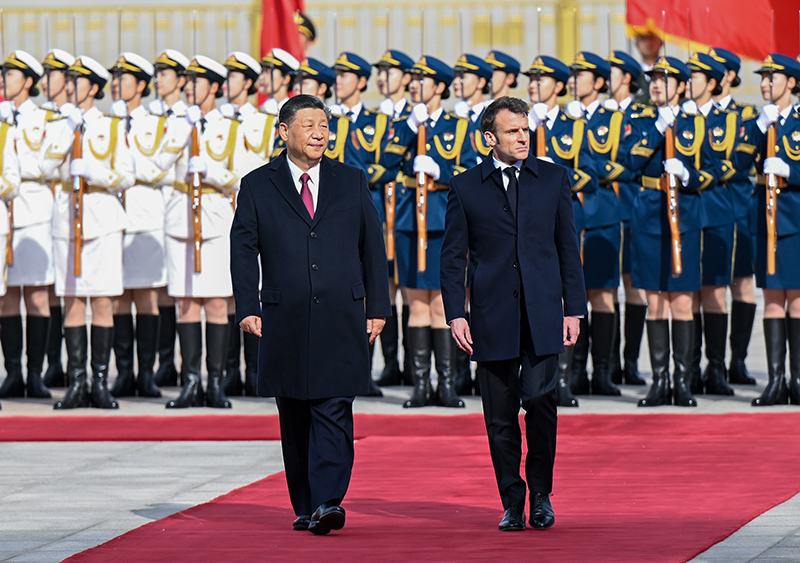

One country, two foreign policies

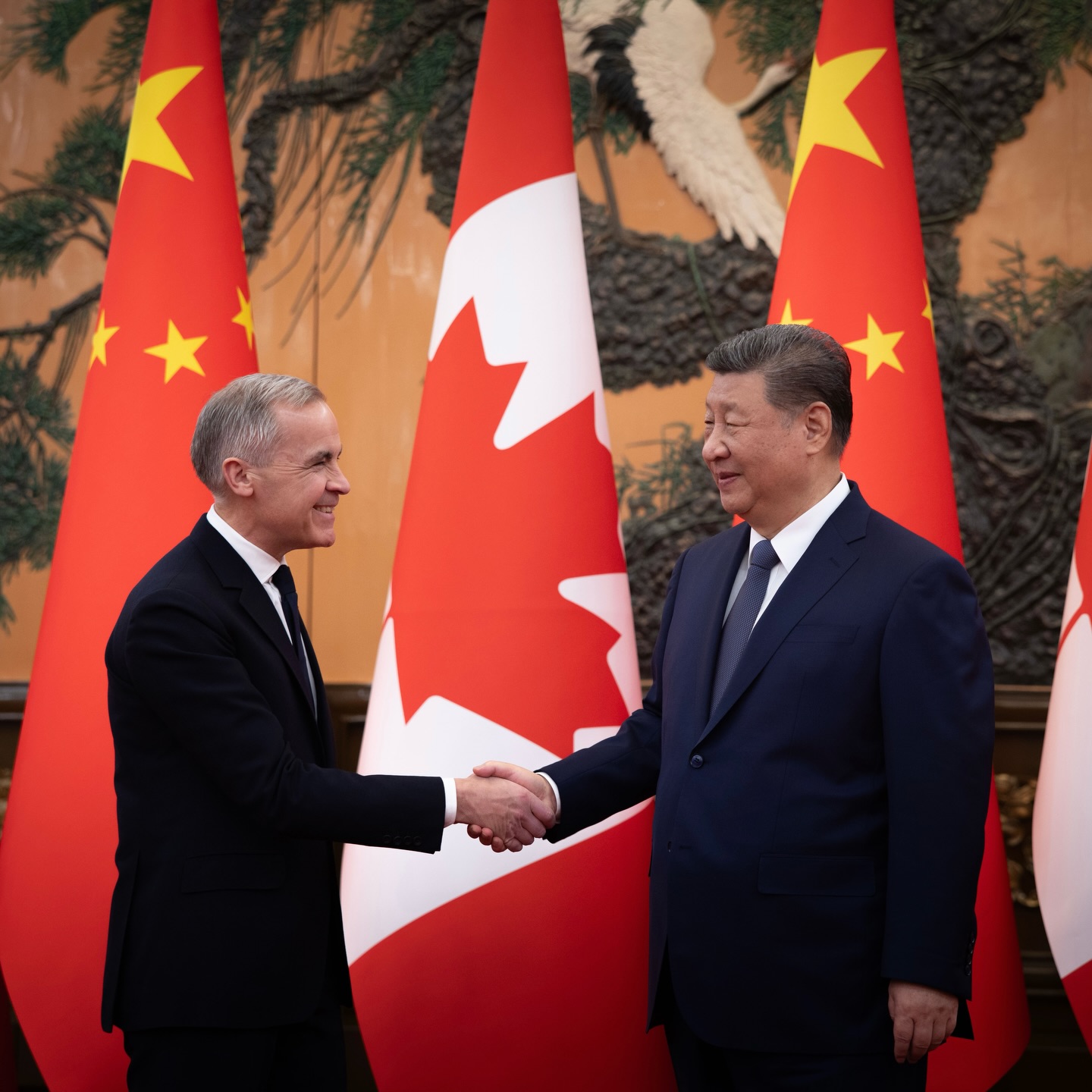

It is perhaps not surprising then that Prime Minister Fiala appears less eager to confront China and its local friends than his Foreign Minister Lipavský. The prime minister for the most part has taken control of foreign policy, with the foreign minister indeed toeing the government’s line as promised to Zeman. The resulting policy towards China, though certainly turned around from the excesses of the previous governments, is nevertheless not as pronounced as some might have expected. It will not follow the Lithuanian example — in fact, that example is viewed in much of the new government as a cautionary tale of going too fast too far.

A case in point is the new government’s approach to the diplomatic boycott of the Olympic Games in Beijing. Prime Minister Fiala has expressed “full understanding” of the boycott, but would not declare it officially. Instead, he simply did not send anybody to attend. In contrast with this discrete, understated position, the president has unabashedly expressed his full and vocal support for the games on several occasions.

Similarly, despite protestations to the contrary, Prime Minister Fiala seems to have made a deal with the president to honor the previous government’s last-minute nominations of ambassadors, however outrageous they may seem. Among the most controversial is the self-nomination of the short-lived last foreign minister in the previous government to become the Czech representative to the U.N. in New York. The new ambassador, Jakub Kulhánek, happens to be a former lobbyist for the China Energy Fund Committee (CEFC), the Chinese company convicted in 2018 before U.S. federal court of high-level political corruption at that very institution, the U.N.

In the tense coexistence between the new government and the old president, the Czech Republic seems to be running two parallel, and contradictory, foreign policies towards China. The president clearly holds the shorter end, and the government may simply consider him no longer relevant and just try to sit him out. He is in poor health, and his mandate ends in early 2023. Nevertheless, he is still able to wage symbolic acts of support for Beijing. Each of these is then immediately amplified by the Chinese Communist Party-controlled media in China.

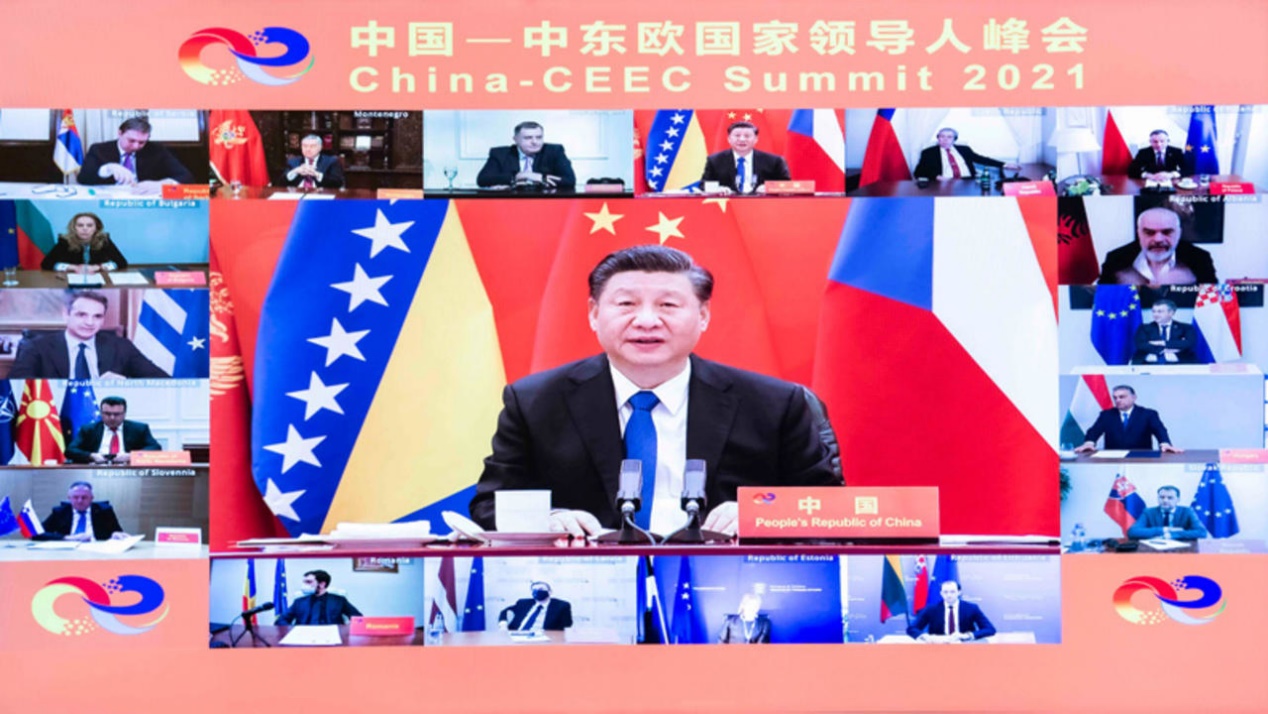

Meanwhile, the new government will gradually revoke, without fanfare, most of the pro-Beijing policies introduced after 2013. It will also pursue closer cooperation with Taiwan — quietly. But it will not, in the near future, stick its neck out by highly visible acts such as unilaterally withdrawing from the 16+1 grouping (though it may do so in coordination with other members).

The wild card, of course, is the current crisis in the Ukraine. Will it convince the government that Russia is the bigger threat to prioritize, or rather that China is the Russian aggression’s enabler? That debate is yet to unfold.

(Dr. Hála is Sinologist with Charles University in Prague, Founder & Director of project Sinopsis.cz.)