Unless the U.S. or the EU find new ways to make Hungary fall in line, there is a fair chance that Mr. Orbán will continue his balancing game between the West and the East. If so, the importance of Hungary may increase further in the eyes of Putin and Xi, as Budapest could be the last EU member ready to offer them political support. Picture source: Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, April 3, 2022, Radio Free Europe,

Prospects & Perspectives 2022 No. 19

The Hungarian Elections and Their Implications for Taiwan and China

By Tamas Matura

April 11, 2022

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his right-wing party Fidesz won a fourth consecutive term with a parliamentary supermajority on April 3. Despite previous expectations, the united coalition of opposition parties could not increase the number of their supporters. Meanwhile, Mr. Orbán strengthened his position in the national assembly: with 53% of the votes, he is expected to control 135 of the 199 seats in the Hungarian Parliament.

In his triumphant speech, the prime minister said: “We have such a victory it can be seen from the moon, but it’s sure that it can be seen from Brussels.” Orbán was alluding to his long-running “fight” against EU institutions and other alleged opponents such as bureaucrats, international media, Ukrainian President Zelensky, and U.S. billionaire George Soros. Based on the tone of his speech a new, conciliatory approach toward Western allies and the EU seems highly unlikely, even though Orbán has managed to further isolate himself internationally, as his response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has outraged whatever friends he still has. Poland, which used to be the other rebel in the EU and a major supporter of Mr. Orbán, has turned its back on Budapest, and the whole future of the so called Visegrad Four cooperation of Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia and Poland is now imperiled.

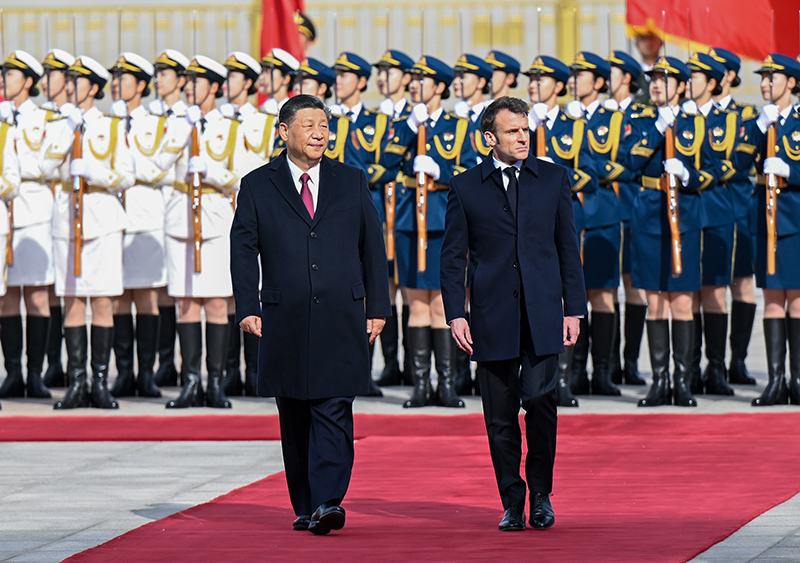

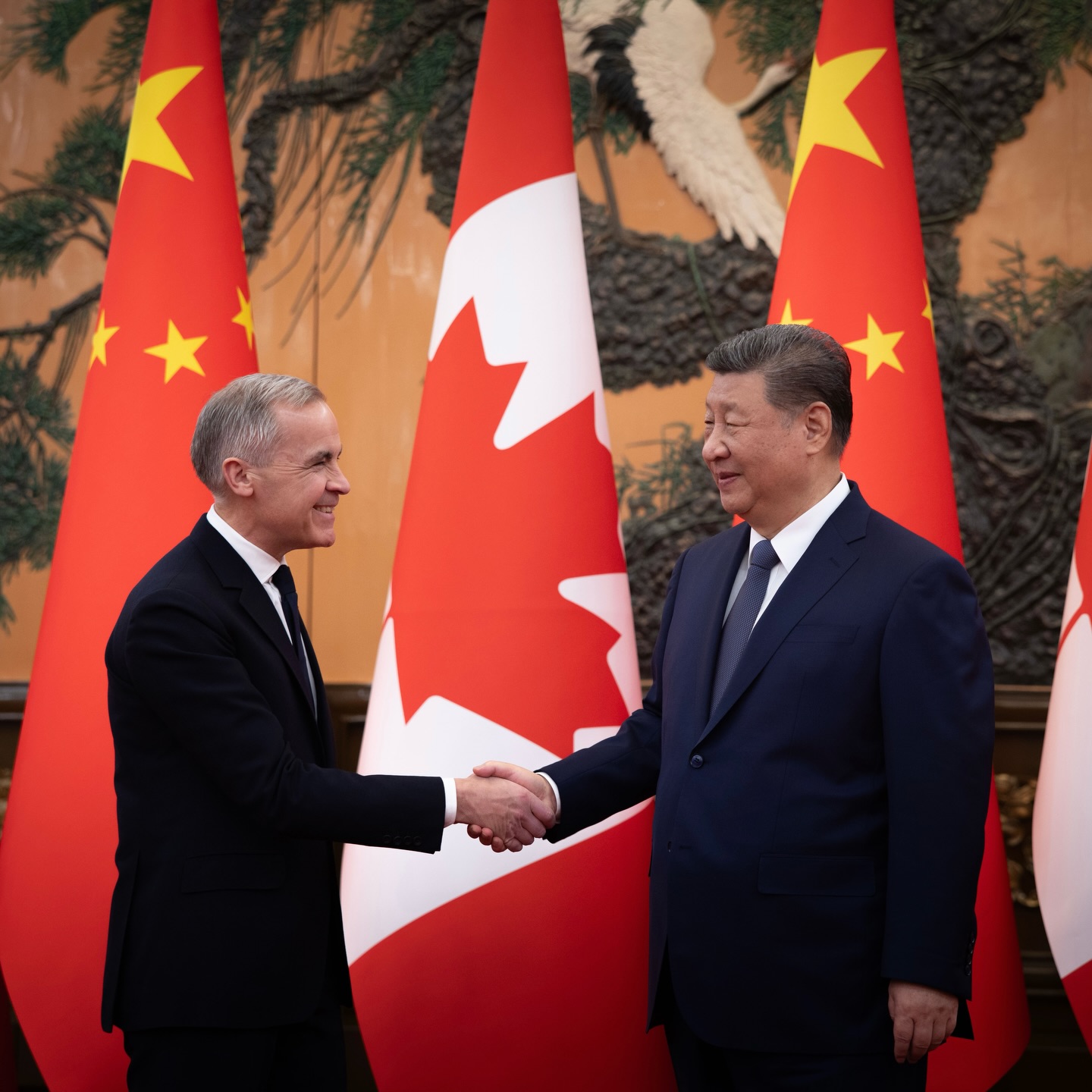

Due to the democratic backsliding of the country and to the strong political connections between Budapest, Moscow and Beijing, the United States has been looking at Hungary with increasing levels of suspicion since the Obama administration. While most observers agree that Mr. Orbán secured the silent support of the German government in the past decade, with the departure of Chancellor Merkel the new government in Berlin may turn more critical toward the domestic and international politics of the Hungarian prime minister. Though Orbán has tried to build a global cooperation of illiberal leaders like presidents Bolsonaro, Erdogan, Xi and Putin, and supported similar movements in the EU such as Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France and Matteo Salvini’s Northern League in Italy, among others, none of these coalitions has borne fruit. Moreover, following Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, being a friend of Mr. Putin has become a stigma around Europe that weakens the international positions of Mr. Orbán and his European comrades.

Orbán’s China Policy

Mr. Orbán was once well known for his fierce anti-communist attitude; during his first term (1998–2002), he had an official meeting with the Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama in his office. However, a decade later, in late 2009 and just a few months before his landslide election victory, he became surprisingly pragmatic and established official party-to-party relations with the Chinese Communist Party in his role as leader of the Fidesz Party. Following his return to power in 2010, Orbán initiated the so-called Eastern Opening Policy in reaction to the economic crisis and to forge better economic relations with China. He visited China numerous times, and elevated bilateral relations to the level of a comprehensive strategic partnership. China became a potential political partner during Orbán’s second term (2010–14), when clashes with the EU and frozen relations with the Obama administration led to the emergence of a political element to China-Hungary relations. Mr. Orbán has mentioned China several times as an alternative to the Western economic system. Just like Beijing, Mr. Orbán rejects the universal validity of political and economic principles and advocates the principle of sovereign non-interference.

Besides political and illiberal ideological considerations, private business interests may also play a decisive role in the pro-China policies of the Hungarian government. Based on media reports, interest groups close to the prime minister have enjoyed the financial benefits of the close relationship between China and Hungary. Hungarian investigative journalists have discovered several links between the main beneficiaries of China-related projects and Hungary’s political elite in the case of a golden visa program, or the reconstruction of the railway line between Budapest and Serbia’s capital, Belgrade, financed, at 85% of the total cost, by a Chinese bank, with actual construction to be handled by the CRE Consortium and companies close to the Hungarian government.

Meanwhile, Budapest has had a two-faced policy vis-à-vis Taiwan. Financial investments from Taiwan is always warmly welcomed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; within the EU, Hungary is only second to the Netherlands in terms of Taiwanese FDI. Foxconn, Giant and the Yageo Holding are among the biggest Taiwanese investors in the country. Meanwhile, when it comes to political cooperation, Budapest always sticks to Beijing’s expectations and keeps relations with Taipei at a very low level. In 2020, Hungary was one of the countries that did not support Taiwan’s accession to the WHO, following a call between the Hungarian and Chinese ministries of foreign affairs.

Mr. Orbán nevertheless decided to tone down his pro-China policies last summer, when his plans to spend 1.3 billion euros in taxpayer’s money on building a huge and brand-new Fudan University campus in Budapest escalated into public protests less than a year before the general elections. Since subsequent issues have diverted public interest, the government’s China policy did not become a major topic in the recent campaign.

What’s Next?

Despite the relatively small size of the country, as an EU and NATO member Hungary has outsized influence in the consensus-based decision-making system of both major institutions. Mr. Orbán has never shied away from using his veto power, and with his renewed supermajority he can easily claim that he has the political legitimacy to do so. Meanwhile, China has been losing clout in the EU, and even more so in the Central and Eastern European member states since many CEE countries now regard the so-called “16+1” cooperation with China as a failure that never delivered on its promises. Lithuania, Czechia, Romania, Poland and others all showed signs of a major foreign policy shift last year, a development that was exacerbated by the Russian aggression against Ukraine. As NATO, the EU and the U.S. all toughen their approach toward Moscow and Beijing, Mr. Orbán’s landslide victory is good news for both autocracies. Unless the U.S. or the EU find new ways to make Hungary fall in line, there is a fair chance that Mr. Orbán will continue his balancing game between the West and the East. If so, the importance of Hungary may increase further in the eyes of Putin and Xi, as Budapest could be the last EU member ready to offer them political support.

(Tamas Matura is an Assistant Professor of Corvinus University of Budapest and non-resident senior fellow of the Center for European Policy Analysis)