U.S. President Joe Biden’s move to recall American troops in Afghanistan, has proved to be a game-changing event for the already delicate regional security environment. Under such circumstances, what are India’s strategic interests and choices in Afghanistan? Does New Delhi’s position complement or contradict that of the Quad nations?

Picture source: Afghan Ministry of Defense Press Office, July 20, 2021, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/why-the-us-wont-be-able-to-shirk-moral-responsibility-in-leaving-afghanistan-164474

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 43

The Quad and India’s Strategic Choices in Afghanistan

August 2021

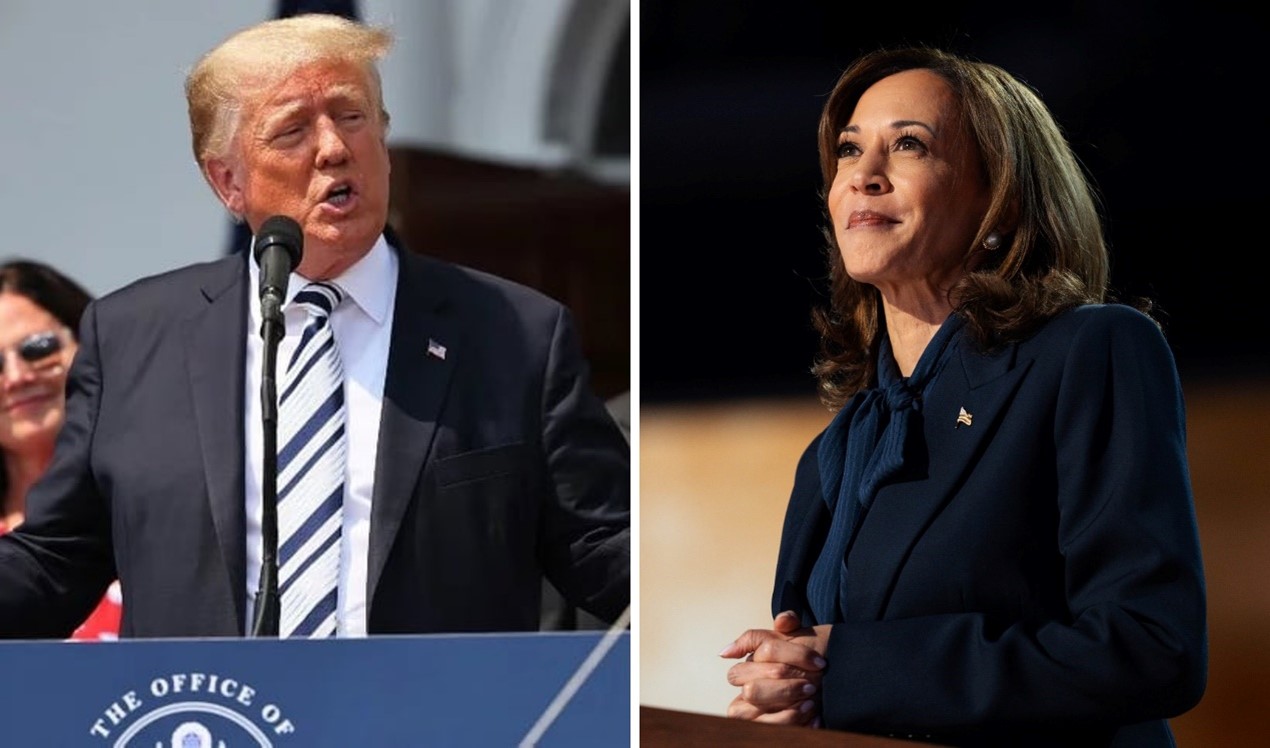

U.S. President Joe Biden’s move to withdraw American troops in Afghanistan, thereby ending the U.S.’ longest war, has proved to be a game-changing event for the already delicate regional security environment. As American forces withdrew from the country, the Taliban took control of Kabul once again after being driven out by the U.S.-NATO alliance two decades ago with a speed that surprised the West — and Taliban themselves. While the move comes as a refocusing of Washington’s priorities from the Middle East to the Indo-Pacific, it also leaves the future of Afghanistan in uncertainty, even as major regional actors like India, China and Pakistan seek to fill the vacuum left by Washington to stabilize the situation. Under such circumstances, what are India’s strategic interests and choices in Afghanistan? Does New Delhi’s position complement or contradict that of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) nations?

India’s Interest in a Stable Afghanistan

New Delhi has been consistent in its official stand supporting an “Afghan-led, Afghan-owned and Afghan-controlled process for enduring peace and reconciliation” in the country. In this context, India welcomed the formation in April 2020 of a team for intra-Afghan negotiations to encourage all political factions to work together for a prosperous and safe future. Simultaneously, India has also been a major contributor of development assistance to Afghanistan, especially in infrastructure, education, humanitarian assistance and capacity building, in accordance with the country’s National Development Strategy. Not only was Kabul one of the first states to receive COVID-19 vaccines from India, but both states also recently signed a MOU to construct the Shahtoot Dam in Afghanistan. This development partnership is supported by high-level political engagements indicating India’s economic and security interests in a robust Afghan state.

India’s investments in Afghanistan have largely been made possible due to the relative stability brought to the country via the presence of American troops. This stability is now at risk as the Taliban reclaim political control and governance dominance over Afghanistan. Taliban’s rapid gains were emboldened by the U.S.-led troop withdrawal and a deadlock in peace talks at Doha. Taliban’s complete military victory in Kabul will prove detrimental for India: Indian assets in Afghanistan have long been targeted by Taliban factions such as the Haqqani group. The U.S. military presence kept in check the radical extremist powers in the country and created the chance of a favorable climate for India to work with Afghanistan.

Now, with the U.S. withdrawal, protecting Indian interests is necessarily dependent upon how well the Afghan government manages and limits the Taliban’s activities. The evacuation of Indian embassy staff and of the ambassador was termed a “difficult and complicated exercise,” even though it is anticipated, and has been discussed widely, that Delhi would like to establish its engagement and dialogue with the Taliban. In other words, the U.S. withdrawal is set to prompt regional terrorism, aided by the reappearance of the Taliban’s effect on Pakistan and the political instability it will create in the area. In this regard, India’s bigger concerns are about the resurgence of the radical factions in Taliban, which could incite extremist actors in Kashmir through India-centered militant groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed; these groups are also believed to have migrated to Afghanistan in huge numbers even as the Taliban has denied ties with both.

Beyond terrorism, India’s strategic concerns in Afghanistan also have to do with the growing influence of China and Pakistan’s intelligence services, especially as both share strong ties with the Taliban. Importantly, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi recently hosted a nine-member Taliban delegation in Tianjin on July 28, 2021, where he highlighted that China expects the insurgent group to play an “important” role in the region. Furthermore, Kabul is reportedly already interacting with China with talks of extending the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) into Afghanistan. CPEC is the flagship economic corridor of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which has cemented the China-Pakistan “iron brotherhood” while threatening Indian sovereignty by passing via Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). Afghanistan’s involvement with the CPEC would decidedly shape China’s entry into Kabul’s political and economic landscape, allowing it to especially seek to fill the power vacuum generated by the absence of U.S. troops. Talks about a China-backed road link between Afghanistan and Peshawar in Pakistan — already linked with CPEC — have also been reported.

Ultimately, China could even achieve greater success than the U.S. in Afghanistan on the grounds of its extensive leverage over Pakistan (Beijing and Islamabad have recently outlined a “joint action” plan to align their strategic postures vis-à-vis Afghanistan) and close ties with the Taliban. Therefore, India’s Afghan policy must anticipate and react diligently to China’s outreach to the region to ensure stability and protect Indian interests. With the Quad states similarly interested in balancing — if not limiting China’s rapidly expanding economic and political footprint in the Indo-Pacific — New Delhi may find opportunities for cooperation with these states.

The Quad’s stake in Kabul’s Future

Over the past year, Beijing has demonstrated itself as a belligerent power interested in securing its great power status rather than upholding a rules-based order to maintain peace and security. For China, Afghanistan is a geopolitically vital state that can offer its military access to the Arabian sea via Pakistan — or even Iran. It can be a link to the Middle East and the Indian Ocean moving on to Africa, possibly marking a threat for the envisioned or future India-Japan collaboration in the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific (part of earlier plans for an Asia-Africa Growth Corridor, now remodeled as the Platform for Japan-India Business Cooperation in the Asia-Africa Region) that is focused on third-country cooperation to form continental connectivity.

Furthermore, tapping into the country’s natural resources has also long figured in China’s mind. The Taliban has already stated that it would support development projects by China in the country, which gives Afghanistan the potential to be a major ground for Chinese strategic overtures in the region. For Beijing, bringing the Taliban on board with BRI is therefore unlikely to be a very difficult endeavor. Strategic assets in Taxkorgan, Wakhan and Gwadar will highly aid China’s economic and political global outreach. Such a Taliban-led and China- and Pakistan-backed Afghan state would leave little room for New Delhi to engage and invest in the country.

Beijing’s role in Afghanistan, backed by Pakistan and the Taliban, is therefore a matter of grave security concern for New Delhi and its strategic partner states like the U.S., Japan and Australia. The Quad must thus emerge as an important stabilizer of the region’s security by coordinating mitigation strategies in areas of convergence. New Delhi must, for instance, aim to build and stay engaged through strong diplomatic and political channels with Kabul that allows for negotiations and advocacy of Indian interests in promoting reconciliation efforts. Besides, India, along with the Quad countries, could aim to establish more training and capacity-building programs that could enhance political confidence in Afghanistan’s reconstruction process.

Although Washington’s withdrawal plans are well underway, the U.S. is not likely to completely disengage post-withdrawal. In his recent visit to India, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken stated that a Kabul under Taliban control would make the country a pariah state, highlighting the strategic commonality and complementarity between New Delhi and Washington vis-à-vis Afghanistan’s future. Similarly, Afghanistan is a concern for both Japan and Australia. This is not limited to the purview of their security alliance with the U.S. As a major contributor to Afghanistan’s development in its own right, Tokyo has a vested interest in peace in the country (with an eye on China) and is set to continue supporting the peace process. Australia too has provided Afghanistan with over $1.5 billion in assistance since 2001 (with more recent figures for 2021-22 stating budget estimates of total Australian ODA to Afghanistan of $51 million) with health security, stability and economic recovery being key areas for assistance in the post-COVID-19 era. Much of this assistance has been in furtherance of human rights (women rights in particular) — values which stand in stark contrast to the Taliban’s and will likely see little attention amid China’s dominant presence in the country. Notably, less than a month after Australian diplomats, military and intelligence personnel left Kabul, Canberra is reportedly considering returning amid “serious doubts about the strategic wisdom of the retreat.” Although there are no formal plans at this point, the Taliban’s resurgence could prompt Australia to re-station intelligence officers to support the Afghan government and perhaps even establish lines of communication with the Taliban, should it become necessary.

Therefore, all Quad states share a key interest in maintaining stability in the region and reaching a peaceful solution among all factions. While their policies on engaging the Taliban may differ slightly, they are nonetheless united in their broader outlooks of securing Afghanistan’s future. In this context, coordinating intelligence exercises and their support to the Afghan government could be a critical initiative under the Quad. Importantly, such an outreach would not be under the U.S. alone, but as part of a joint Quad effort to uphold security of the Indo-Pacific. For India, a coordinated response with Quad actors can further support its effort to solidify its role as a security actor in the region. Even for China, the Taliban’s return was not an entirely desired scenario, given concerns of exacerbated terrorism, an increased ISIS presence and Uyghur extremism creating instability in the Xinjiang autonomous region — as indicated by Foreign Minister Wang’s hope that the Taliban will “denounce” terrorism and focus on administrative politics. Here, the Quad could perhaps even find common ground with Beijing (and Russia) to present a well-coordinated response to a (radical?) Taliban with the aim of facilitating an Afghan-led, and Afghan-owned, peace process.

(Dr. Jagannath Panda is a Research Fellow and Centre Coordinator for East Asia at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. Dr. Panda is the Series Editor for “Routledge Studies on Think Asia”.)