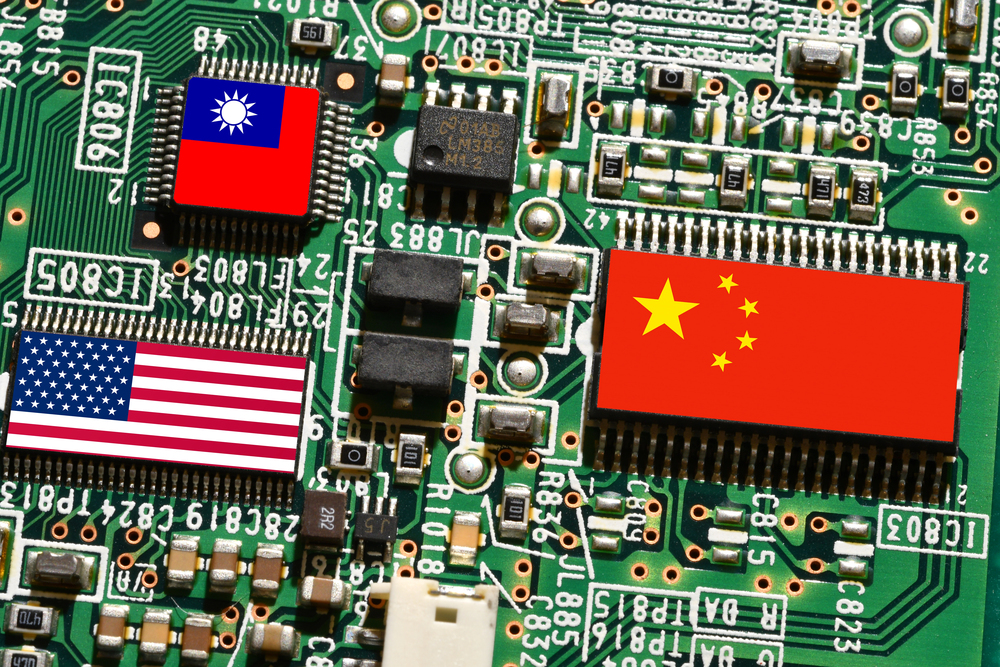

These are tough times for the U.S.-India strategic partnership. Over the last few months, President Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi have sparred over various issues, including U.S. reciprocal tariffs (currently at 25%), U.S. sanctions for India’s continued import of discounted Russian oil (another 25%), and an apparent reset in U.S.-Pakistan ties. Recent disagreements have sunk Washington and New Delhi’s relations to the lowest point since 1998. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 52

The U.S.-India Partnership Will Survive, Maybe Even Thrive

By Derek Grossman

These are tough times for the U.S.-India strategic partnership. Over the last few months, President Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi have sparred over various issues, including U.S. reciprocal tariffs (currently at 25%), U.S. sanctions for India’s continued import of discounted Russian oil (another 25%), Trump’s claim that he personally brokered a ceasefire to end the India-Pakistan conflict in May, and an apparent reset in U.S.-Pakistan ties. Recent disagreements have sunk Washington and New Delhi’s relations to the lowest point since 1998, when India tested nuclear weapons and the U.S. responded with sanctions.

But all certainly isn’t lost. In a breakthrough of sorts, Trump and Modi in early September exchanged pleasantries over social media and noted that they planned to discuss resolving trade barriers. Doing so could also pave the way for Trump to reverse his reported decision not to attend the Quad summit, to be hosted by India later this year, which could significantly put U.S.-India relations back on track.

No fundamental changes

The reality is that the last few months have merely been an aberration. Indeed, over the last 25 years, and especially in the last five to 10 years, the U.S.-India strategic partnership has flourished due to many common interests and concerns, not the least of which is to counter China throughout the Indo-Pacific. In 2017, for example, India rejoined the Quad (along with Australia, Japan, and the U.S.) in large part to coordinate activities against China. Beijing then did itself no favors in the spring of 2020 when it launched a limited military invasion of Indian-held land along their disputed border in the Galwan Valley of the Ladakh region, resulting in the first lethal clashes in decades. Seemingly overnight, Indian sentiment pivoted from being suspicious of and distant from China to staunchly and openly against it. This has promoted closer U.S.-India strategic relations — and nothing has fundamentally changed since then.

And yet, a quick scan of the headlines over the last few weeks might make it feel like something has. From August 31 to September 1, Modi visited Tianjin — his first trip to China in seven years — to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit. From one perspective, this was a multilateral security and economic forum that India has been a part of now for many years, and so Modi’s attendance in and of itself was not a particularly big deal. However, given the currently abysmal state of U.S.-India relations, Modi’s visit had added symbolic meaning. By meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin, Modi was signaling New Delhi’s deep displeasure with Trump and a willingness to engage in new world order without the United States. Indeed, even Trump lamented that the U.S. had “lost” India to “deepest, darkest” China.

Context matters

All of these developments must be placed within their proper context. On China, there has been a clear rapprochement, especially since Beijing and New Delhi reached an agreement in October for the complete withdrawal of Chinese military personnel from their newly-established outposts in Indian-held territory. However, deep distrust and anger toward Beijing persists, as shown by a recent Pew Research poll, which found that 54% of Indian respondents hold an “unfavorable” view of China versus just 21% who hold a “favorable” one.

While India’s strategic partnership with Russia is deep and longstanding, it has also become apparent that New Delhi has less and less in common with the Kremlin. Even if only in a subtle way, Modi has come out against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, telling Putin in 2022 that “today’s era is not of war and I have spoken to you about it on the call.” Moreover, if their oil trade is put to the side, India-Russia trade has actually been declining over time, falling just 33.5% from June 2024 to June 2025. Indian imports of Russian military equipment — historically, the most reliable source of their cooperation — is also on the decline, from 72 percent of New Delhi’s total arms imports from 2010 to 2014 to 36 percent from 2019 to 2023. India is replacing Russian systems with American and other systems for a range of reasons, to include ensuring future interoperability and decreased dependence on Moscow, while Russia pays less attention to arms sales abroad because of its war in Ukraine.

At the end of the day, India remains staunchly non-aligned, or, from another perspective, multi-aligned, to protect and promote its national interests. In practice, this means continuing to maintain a close working strategic partnership with not only the United States, but Russia and China as well. That said, New Delhi in recent years has shown its hand, and it leans heavily toward the U.S. to avoid becoming entrapped in a new world order, led by Moscow and Beijing, that would provide fewer benefits and security assurances. Because there are so many more upsides to dealing with the U.S., whether on defense, technology, global health, energy, and so on, New Delhi is very likely to still prioritize engagements with Washington over all others.

Points of contention

Of course, the sticky question of how to handle India’s continued import of heavily discounted barrels of Russian oil persists. The Trump administration may consider this as part of a new trade deal, or, like the Joe Biden administration did, simply agree to disagree on the issue and pursue other means of choking off the Kremlin’s war machine. Indeed, Trump has already signaled this might be a possibility by floating the idea that the EU should put heavier sanctions on China and India for importing Russian oil, possibly giving Washington some breathing room on the issue. All of this remains to be seen, however. Another challenge is the Trump administration’s ongoing reset with Pakistan, though this is probably more manageable so long as Islamabad’s influence in the White House doesn’t surpass that of New Delhi — and for now, India remains dominant.

For Taiwan, these complex geopolitical dynamics could create a less comfortable international environment. Great power competition between the U.S. and China is already quite intense, and new struggles to win hearts and minds in New Delhi only add to the frictions. Additionally, the U.S. has tried to complicate Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has Chinese support, by punishing India, and this approach has failed thus far. The good news is that because U.S.-India relations are likely to survive, and even thrive after the current storm passes, closer unofficial ties with both Washington and New Delhi would not exacerbate differences between them, and probably would further strengthen the network of fellow democracies working toward the common goal of taming China’s worst ambitions.

(Derek Grossman is a Professor of political science and international relations at the University of Southern California. He formerly served as a senior defense analyst at RAND and the daily intelligence briefer to the assistant secretary of defense for Asian and Pacific security affairs at the Department of Defense.)