Past Performance to Guarantee Future Return? Navigating Singapore’s External Relations at Time of Transition

Singapore and Singaporeans have bet on what they know best, but like all bets there is a chance of things going awry. How Singapore seeks to update its range of external policies for a more contested, protectionist, and less restrained world in practical terms is uncertain even as economic negotiations with the Trump administration have yet to produce visible results. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 36

Past Performance to Guarantee Future Return? Navigating Singapore’s External Relations at Time of Transition

By Ja Ian Chong

Singapore’s fifteenth general elections took place on May 3, 2025, under the shadow of unease cast by the Trump administration’s global tariffs and the ongoing trade war between the United States and People’s Republic of China (PRC). For many observers, the long dominant People’s Action Party (PAP) performed better than expected under new Secretary-General and Prime Minister, Lawrence Wong, securing about 65 percent of the popular vote and 87 out of 97 contested seats. The Workers’ Party consolidated its position as Singapore’s leading opposition party by winning 10 seats and securing an additional two Non-Constituency Member of Parliament seats by coming just short of victory in two additional constituencies. The Workers’ Party averaged 50.04 percent of votes in the wards they contested. These results reflected a vote for familiarity in the face of uncertainty.

The question facing Singapore, however, is whether same old is still good enough. This issue is especially salient given ongoing global changes. Given its size and need for connectivity, Singapore is especially sensitive to shifts in its outside environment world. As a smaller state its success over the past decades rested on the relatively stable and predictable international environment of the post-World War II and post-Cold War periods, coupled with the trend of rising economic liberalization. Such conditions enabled a worldwide flow of capital, services, and merchandise from which Singapore was able to find and seize opportunities for growth—albeit with a degree of inequality. The recent turn away from globalization and toward industrial policy along with decreasing interest in international institutions among the world’s largest and most developed economies puts pressure on Singapore’s model for prosperity.

Changing Circumstances

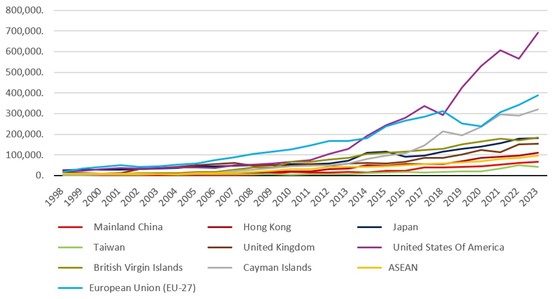

A common perception is that Singapore is economically dependent on the PRC. This is inaccurate. The United States is persistently Singapore’s largest source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) by far alongside Japan, the European Union (EU), and various tax havens, just as these economies are among Singapore’s largest trading partners in services. Singapore re-exports some of this capital and services to the rest of Southeast Asia and the PRC, while applying the rest to importing and exporting merchandise for domestic consumption, production, and re-export. The services sector is particularly crucial as it accounts for roughly three quarters of employment in Singapore. The PRC is Singapore’s largest trading partner in merchandise, above Malaysia, the United States, and other parts of Southeast Asia. Singapore has a trade deficit with the PRC, but this is sustainable so long as it can re-export or export finished merchandise using PRC parts to third markets. Disruptions to key elements of this model for economic circulation are likely to present challenges to Singapore.

Figure 1. Top Sources of Inbound FDI to Singapore (S$ millions)

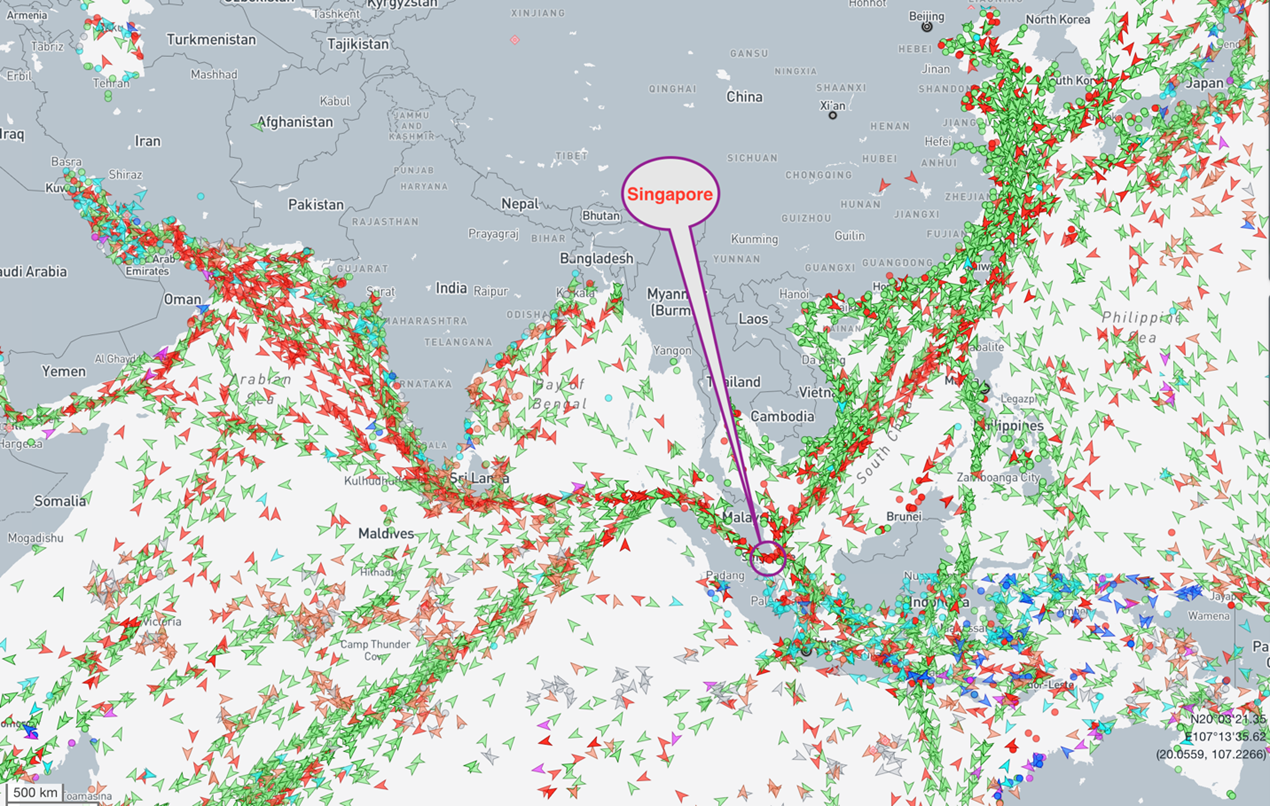

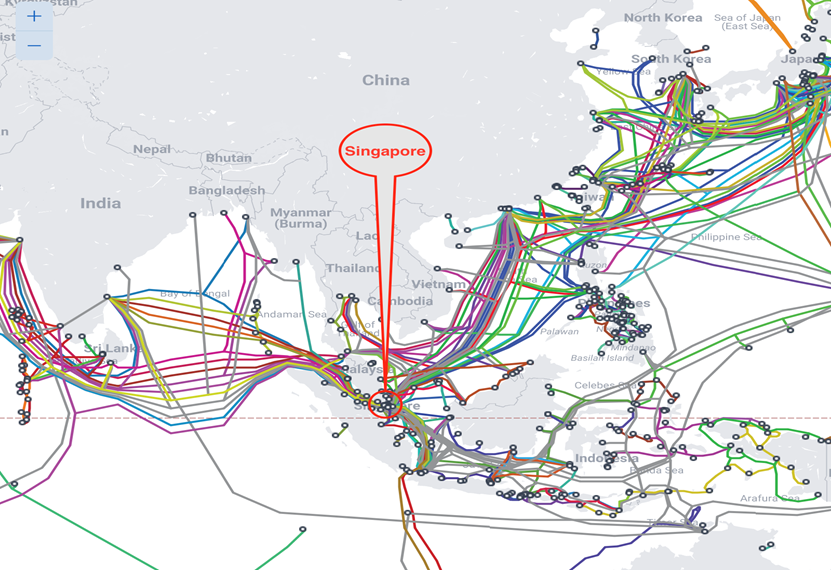

Even though Singapore has long invested heavily in defense and is more than able to protect itself against most direct, immediate threats, its prosperity and security also depends on a stable and predictable environment with minimal use of force and coercion. Highly extended lines of communication are critical for Singapore. Shipping lanes bring merchandise, including fossil fuels and food, between Singapore and everywhere from East Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Air routes traversing the world supplement these links by bringing people and high value merchandise in and out of Singapore. Financial and commercial activity relies on the web of undersea cables running around the world. Singapore is unable to prevent or restore disruptions and blockages to these critical lines of communication on its own.

Figure 2. Singapore Maritime Traffic

Figure 3. Singapore Submarine Cables

Strategic Advantages

Over the past decades, Singapore saw advantage in the relative stability and access afforded by global American power and commercial interests. Successive Singapore administrations were, therefore, willing to work closely with Washington to safeguard its own strategic and economic concerns. Singapore provided U.S. forces access to its military facilities in 1990, renewing the arrangement in 2019, concluded a strategic framework with Washington in 2005, and added multiple enhancements subsequently. These agreements allowed the United States military use Singapore’s naval bases and airports as a transit point and logistic hub while Singapore increased its acquisition of U.S. military equipment and enhanced bilateral security cooperation. Singapore does not have a formal alliance relationship with the United States. Nonetheless, as U.S. focus on its global role fluctuates and becomes less clear, Singapore may question the reliability of an important pillar undergirding its security.

Another key component of Singapore’s security and prosperity lies in the relative efficacy of international institutions and law, however imperfect and flawed. Respect for sovereignty after World War II along with permissive neighbors enabled smaller countries like Singapore to eke out diplomatic and political space for survival and international standing. The United Nations system as well as legal channels like the International Court of Justice and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provided Singapore with voice opportunities, recourse, and means to handle differences without force. General compliance with mechanisms like General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade subsequently the World Trade Organization (WTO) as well as various agreements helped smooth economic ties, even providing some ability to handle disputes. These institutions and regimes now face pressure from major powers less accepting of the restraints they impose and seek instead to either ignore or bend arrangements to their will.

Betting on the Familiar

If notoriously risk-averse and skittish Singaporean voters chose familiarity last May, it remains less clear how Singapore’s tried and tested formula for managing its external environment will fare going forward. Basic conditions that underpinned Singapore’s many accomplishments since independence in 1965 and following the end of the Cold War are now in flux. Where these changes will lead remains unknowable at this point. Whether and if the approaches to managing outward ties Singapore have known since independence can still deliver in the same ways or if Singaporeans and their partners need to recalibrate expectations are unclear. Singapore and Singaporeans have bet on what they know best, but like all bets there is a chance of things going awry. At the time of writing, how Singapore seeks to update its range of external policies for a more contested, protectionist, and less restrained world in practical terms is uncertain even as economic negotiations with the Trump administration have yet to produce visible results.

(Dr. Chong is Associate Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore.)