World leaders who attended the G7 Summit expressed serious concerns about the threats to the international order by authoritarian states such as Russia and China. They view the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine as a conflict that poses a fundamental threat to international security and principles such as human rights, territorial integrity, and democracy.

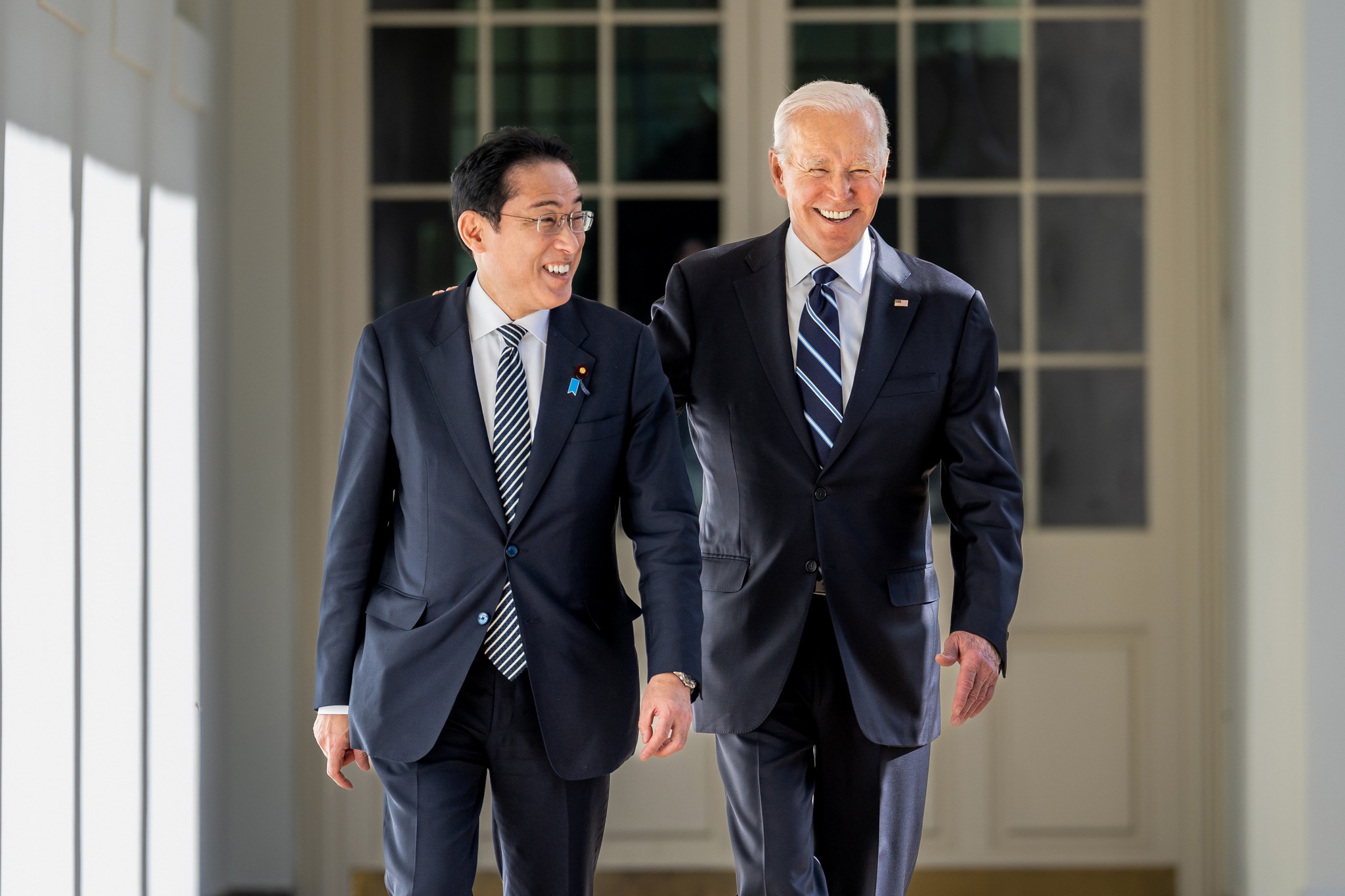

Picture source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, May 19, 2023, G7 HIROSHIMA 2023, https://www.g7hiroshima.go.jp/assets/bg_mv_05.052f242e_m0t2u.jpg.

International Security after the 2023 G7 Summit

Prospects & Perspectives No. 31

By Hung-jen Wang

World leaders who attended the G7 Summit in Hiroshima, Japan, on May 19-21 expressed serious concerns about the threats to the international order by authoritarian states such as Russia and China. They view the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine as a conflict that poses a fundamental threat to international security and principles such as human rights, territorial integrity, and democracy.

The Ukraine war has increased awareness among G7 leaders that any location in any region has the potential to become a battlefield — the spillover effect from the war has increased awareness of the tentative balance in the Indo-Pacific that affects the mindsets of political leaders. We are only beginning to understand how the Ukraine war is affecting established power relations among Russia, the EU, China, and the U.S., and how regional leaders are being forced to recalculate their efforts to promote or protect their interests. This restructuring process is in turn strengthening security relations between Europe and Indo-Pacific countries, which explains why G7 leaders and other invited heads of state, including several from the global south, expressed concerns about developments in Ukraine, and how these might increase the potential for confrontations in Asia.

There is evidence that G7 leaders now perceive China as threatening international society in ways that must be dealt with soon — note British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s statement to reporters at the G7 meeting that “China poses the biggest challenge of our age to global security and prosperity.” This is a significant change from prior G7 comments in support of an ambiguous policy toward China. The shift to adopting a consistent collective policy is exemplified by a statement approved by G7 leaders to maintain stability in both the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan has publicly stated that U.S. President Joseph Biden has not changed American policy regarding China-Taiwan relations — despite the fact that on at least four occasions, Biden has told reporters that the U.S. will defend Taiwan from a Chinese invasion.

With the G7 Summit now concluded, observers are speculating on how the foregoing concerns will impact established international security policies and practices. Any impact will likely reflect concerns in five areas:

1. There are many questions regarding how the international community (especially Western countries) might re-consider economic relations with China. Summit attendees expressed concerns not only about China’s military power, but also about what they perceive as acts of economic coercion toward the its trading partners. Addressing the a U.S. House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee, Victor Chia, Senior Adviser and Korea Chair with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, described China’s coercive economic tactics and how the Chinese government punishes countries and companies that are economically dependent on the Chinese market for perceived violations of “one China,” or who criticize China’s human rights environment.

While the G7 leaders fully understand the impossibility of a full decoupling from the Chinese market, they appear to be considering the costs of pursing a de-risking or diversification policy. The obvious question is whether such policies can be executed collectively, since any individual attempts are certain to attract retaliation from the economically dominant China. There is some speculation of creating an “economic NATO” for purposes of collectively resisting unreasonable sanctions enacted by Beijing.

2. Developments in Sino-U.S. relations will continue to significantly affect international security, especially in the Indo-Pacific region. It is likely that we will continue to witness ongoing fluctuations in this relationship, but there is reason to believe that the potential for a “worst case” scenario is low. During the Summit, President Biden predicted a thaw in the relationship, but it is still possible that we will see both new opportunities and new tensions. On June 5, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that Daniel Kritenbrink, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, and Sarah Beran, senior White House National Security Council director for China and Taiwan affairs, visited Beijing. The purpose of the meeting was to “frankly exchange” ideas regarding core Chinese principles such as Taiwan “reunification.” However, between the G7 Summit and this early June meeting, a Chinese J-16 fighter jet aggressively intercepted a U.S. Air Force reconnaissance aircraft over the South China Sea, and a Chinese warship crossed the path of an American destroyer and Canadian frigate in the Taiwan Strait, an act designed to prevent the U.S. from legitimizing its freedom of navigation claim in the Strait, which Beijing now describes as internal Chinese territory.

These examples of diplomatic meetings and expressions of military power are likely to continue, with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken planning to visit China in late June or early July, and with some speculation about another official meeting between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and President Biden. It is difficult to believe, however, that the two governments are actually on a path to establishing a true friendship, or for Xi to ever succeed in his desire for “a new type of major [great] power relationship” (“xinxing daguo guanxi”). Divisions will continue to drive competition between the two countries, with neither side accepting the other’s ideology.

3. China and the U.S. are competing for support from “like-minded countries” to build leverage in international organizations and to defer criticism. For example, we are witnessing the division of countries into pro-Ukrainian/U.S. and pro-Russian/Chinese camps. It is reasonable to argue that China is more eager than the U.S. to attract other countries to its side, based on Beijing’s acknowledgment that one day it might have to deal with isolation from a U.S.-led international coalition. Although China has always claimed that its foreign policy principles are based on a non-alignment policy, Xi has influenced the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and government to actively pursue various types of partnerships with other countries. For example, on May 18 and 19, just before the G7 Summit, the leaders of China and Central Asian countries held their first in-person meeting in Xi’an, the historical terminus of the ancient Silk Road. The timing with the beginning of the Summit was not coincidental.

The Xi’an meeting also marks the success of long-term efforts by Beijing to solidify relations with Central Asian states. In September 2022, Xi had made his first foreign trip to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan since the beginning of the Covid pandemic, just before his expected reappointment as CCP leader at the 20th Party Congress. It is unusual for Chinese leaders to make official visits when preparations are being made for important domestic political events, but there was special motivation for Xi’s trip to Uzbekistan for the annual meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization: a sideline consultation with Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Xi’s trip and meeting with Putin occurred during a tense period in U.S.-China relations, one month after a visit to Taiwan by then-U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

4. Presidential elections in both Taiwan and the United States are scheduled for 2024, and China will likely try to influence their results. During previous Taiwanese elections, China used agents to express its positions in local media, including misinformation meant to confuse the voting public on “facts” regarding China. There is also evidence of Beijing using cyber espionage to manipulate the information environment within Taiwan. According to a recent report issued by the Five Eyes alliance — the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the U.S.—the Chinese government is training a “Volt Typhoon” hacker group in the use of stealth techniques to manipulate security concerns in various international regions. The group is believed to be bypassing internet safeguards to launch persistent long-term attacks on local political leaders and authorities.

Following the 20th CCP Congress, Xi appointed Song Tao, formerly in charge of the Party’s outreach with other political parties around the world, as director of the Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO). One of his primary political tasks is to persuade Taiwanese elites and leaders that China is open to considering different opinions from Taiwan, but only if Taipei accepts the so-called “92 consensus.” China describes this idea as confirming Taiwan’s support for the “one China” principle, while Taiwan describes it as a minor concept with no diplomatic weight. Despite Song’s claim of sincerity in hearing alternative views from Taiwan, China has no plans to give Taiwan any freedom in considering alternatives to its demands.

5. Post-G7 Summit, international security issues will also continue to be influenced by the Ukraine War. Stability in three Asian flashpoints — the Korean Peninsula, the Taiwan Strait, and the South China Sea — is highly dependent on developments in the Ukraine war. Whether Putin retains or loses power will likely affect how leaders in China, North Korea and the United States manage their political strategies in Asia. It should be noted that NATO, which is at the center of the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, is planning to open a liaison office in Tokyo (a move that is opposed by the French government). The office is expected to facilitate periodic consultations between NATO, Japan, and South Korea regarding the expanding military challenges posed by China and North Korea. This action might be viewed as acknowledgment of a possible Asian spillover effect resulting from the Ukraine War.

In conclusion, it is unlikely that a Ukraine-Russia peace agreement will occur anytime soon, and evidence from the latest G7 Summit shows that its members are preparing for the potential effects of a long-term armed conflict in that region on relations among China, North Korea, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and the United States, as well as associated strategic activities across Asia. Fluctuation will continue to be the primary characteristic of relations between the two most important members of that group — China and the U.S. — with both countries motivated by their respective insecurities, and with diplomatic moves reminiscent of Cold War divisions.

(Dr. Wang is Professor, Department of Political Science, National Cheng-Kung University.)