In Response to Asymmetry: The Philippines’ Approaches to the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea

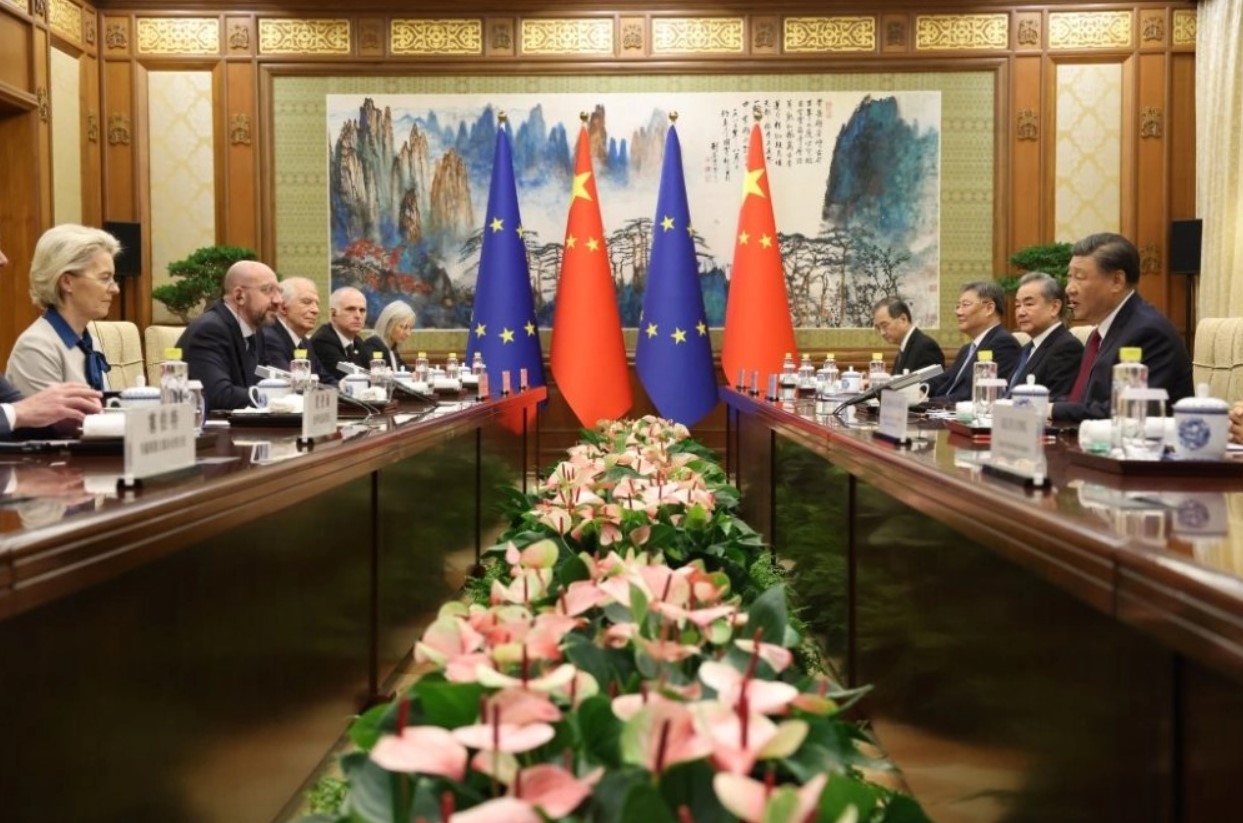

The Marcos administration seems to have decided to mobilize international and domestic public opinion to push the PRC to exercise more restraint. Behind this approach was probably a recognition that attention from Washington could prompt greater care by the PRC, as well as realization that the Philippines was unlikely to escape any confrontation between U.S. and PRC interests unscathed. Picture source: The White House, May 1, 2023, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/whitehouse/52940482116/in/album-72177720307683824/.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 22

In Response to Asymmetry:

The Philippines’ Approaches to the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea

By Chong Ja Ian

Despite popular interpretations of these events as an escalation in tensions, the Philippines’ actions have, for now, led to some PRC restraint.

‘Relatively moderate’

Compared with developments between 2012 and 2017, there appears to be a limit to the intensity of actions in the South China Sea. That period witnessed the sinking of vessels from ramming as well as the detention of ships and crew. Dramatic as behavior in disputed waters between the Philippines and PRC may be, similar events have not occurred despite PRC numerical superiority and the much larger displacement of deployed PRC vessels. The Philippines has also been able to minimally resupply their Marines deployed on the BRP Sierra Madre, a World War II-era landing ship deliberately beached on Second Thomas Shoal to maintain a presence. Second Thomas Shoal is about 100 nautical miles off the Palawan coast, within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), but within the under-defined nine- (and sometimes 10–) dashed lines that the PRC demarcated as their waters.

A reasonable reading of Beijing’s behavior is that it is wary of appearing excessively aggressive when Manila is actively broadcasting what is happening at sea to the world. Beijing rejects the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling and refused to actively participate in proceedings, making only public statements while accusing the Tribunal of having no jurisdiction and arguing that the process is fundamentally flawed. Such strong claims notwithstanding, PRC leaders apparently prefer that the world see them as relatively moderate and careful even when advancing their claims. They would rather continue the harassment of Philippines vessels in the expectation that the world would lose interest and Manila would be unable to sustain its presence on Second Thomas Shoal. Even if far from the ideal of using purely diplomatic and legal means to handle the dispute while refraining from action that could alter conditions on the ground, Manila’s publicity and transparency campaign seems to have encouraged more PRC moderation.

Managing Beijing

Manila’s actions represent a change in its approach to managing the South China Sea dispute with Beijing. Cognizant of capacity limitations and serious capability asymmetries relative to the PRC, the Philippines experimented with different ways of addressing its differences with the PRC over several presidential administrations. The Macapagal-Arroyo administration adopted a more conciliatory position, seeking cooperation with Beijing, while the Aquino administration adjusted to using legal means through the UNCLOS arbitral tribunal process to clarify the basis of claims. The Duterte administration sought to actively court Beijing economically and politically with a view that cooperation on other fronts could facilitate compromise and even concessions. None have effectively resulted in PRC moderation or even substantive, visible progress on a South China Sea Code of Conduct (COC) under the auspices of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to govern behavior and prompt de-escalation.

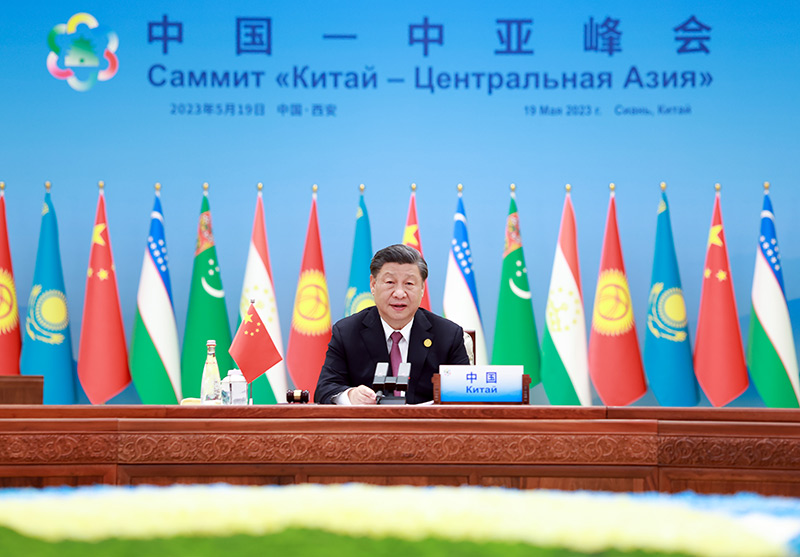

The Marcos administration seems to have decided to mobilize international and domestic public opinion to push the PRC to exercise more restraint. Behind this approach was probably a recognition that attention from Washington could prompt greater care by the PRC, as well as realization that the Philippines was unlikely to escape any confrontation between U.S. and PRC interests unscathed. The latter point was made emphatically by Beijing’s demarcation of an area just off the Philippines’ northern territorial waters as a missile test zone as a response to U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in 2022. Experience surrounding the Arbitral Tribunal process and COC negotiations probably helped further convince the Philippines’ leaders that ASEAN and other member states were unlikely to risk friction with Beijing. This despite the fact stabilizing disputes is in the collective regional interest.

Internationalizing the issue

The Philippines consequently sought to both highlight PRC behavior at sea, revitalize the Philippines-United States alliance, and develop capabilities with the assistance of the United States and its regional allies. Closer defense and security cooperation with Washington meant that U.S. assets monitor maritime encounters in the South China Sea between the Philippines and PRC from nearby. Washington also issues reminders that attacks on Philippine military vessels and sovereignty could invoke the U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty. Cooperation with the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Australia have significantly enhanced the Philippines’ military and coast guard capacities. All these states have interests in the unfettered access to and safety of sea lanes, air routes, and submarine cables traversing the South China Sea, given the needs of trade, fossil fuel imports, communications, and treaty commitments. In return, Manila provides the United States with greater base access and provisions to pre-position equipment to be used in a contingency on Philippines territory.

Manila’s approach to the South China Sea is instructive for actors looking to manage differences with an assertive, more powerful rival despite clear asymmetries in capability. The approach depends on the more powerful actor having some sensitivity toward international public opinion, the availability of other, more capable supporters, and acceptance that greater escalation may result without decisive action. Beijing is, after all, keen to maintain an image that it is restrained and moderate despite wanting to also show that it is resolved and robust in protecting what it sees as its interests. Nonetheless, danger that risky behavior at sea can result in some accident that results in unintended and uncontrolled escalation, especially if there is the inflaming of public opinion that limits possibilities for compromise. For the moment, Manila appears to have discovered a means to defend its position despite a much weaker hand.

(Chong Ja Ian is Associate Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore and a non-resident scholar at Carnegie China.)