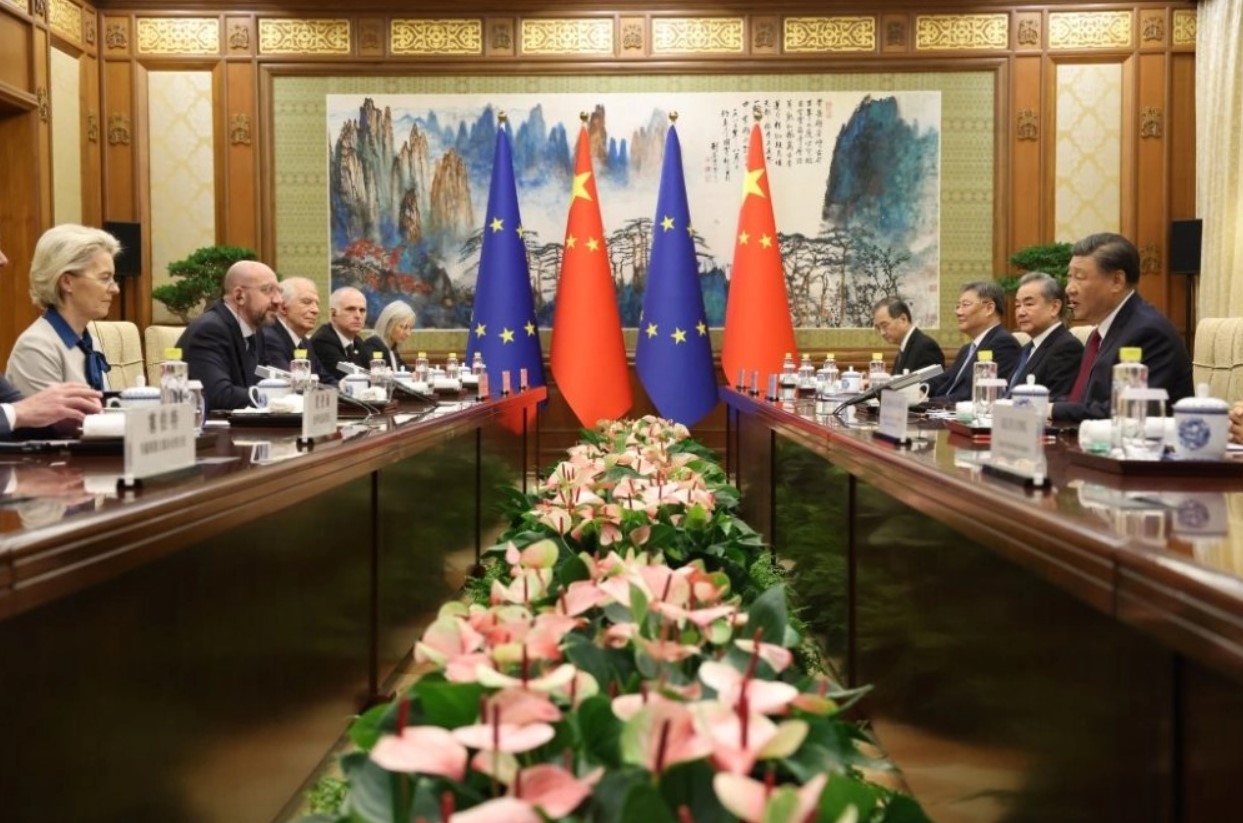

On December 7, 2023, the EU and China held a summit in Beijing. Brussels is increasingly concerned about China’s role in Russia’s evasion of EU sanctions, restricted market access for European companies in China, its ballooning trade deficit with China, and Beijing’s growing belligerence in the Indo-Pacific region, including in the Taiwan Strait. Picture source: Josep Borrell Fontelles, December 7, 2023, X, https://twitter.com/JosepBorrellF/status/1732777046294573237/photo/1.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 7

Another ‘Dialogue of the Deaf’? Evaluating the 24th EU-China Summit

By Marcin Jerzewski

On December 7, 2023, the EU and China held a summit in Beijing, marking the first in-person EU-China summit since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, and European Council President Charles Michel, accompanied by High Representative Josep Borrell, represented the EU. They met Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang at two separate sessions.

On the one hand, the in-person meeting among the highest-level representatives of both entities signals that Beijing and Brussels remain committed to keeping the channels of communication open. On the other hand, the space for their cooperation has been shrinking. Brussels is increasingly concerned about China’s role in Russia’s evasion of EU sanctions, restricted market access for European companies in China, its ballooning trade deficit with China, and Beijing’s growing belligerence in the Indo-Pacific region, including in the Taiwan Strait.

These concerns are not novel. In 2022, Borrell ventured to describe the online EU-China Summit as “the dialogue of the deaf” in light of China’s lenient position on the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. This year, not much progress was achieved either. Not only did Beijing fail to commit to withholding its tacit support for Putin’s regime, but also neither side identified mutually agreeable solutions for addressing the unbalanced trade relations between the EU and China. These intractable tensions effectively turned the most recent EU-China Summit into another “Dialogue of the Deaf.”

‘We Like Competition, But It Needs to Be Fair’: Addressing Trade Imbalance

The EU and China are close economic partners, with the EU exporting goods worth approximately 230 billion euros (US$249.3 billion) to China in 2022. However, that same year, the EU’s trade deficit rose to a whopping 400 billion euros. Brussels attributes this pronounced unevenness to Beijing’s unfair trade practices. The issues range from restricted market entry for European companies in China, preferential treatment of Chinese firms, including generous subsidies and price distortions, and China’s production overcapacity in sectors such as steel and electric vehicles which then inundate the European market.

In her statement following the Summit, the European Commission’s von der Leyen commented, “European leaders will not be able to tolerate that our industrial base is undermined by unfair competition; [...] we insist on fair competition from companies that come to our Single Market.” This was not an isolated statement, and the recent efforts of the European Commission to narrow the gap in trade between the EU and China are not limited to mere rhetorics. In October, the Commission launched an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric vehicles, which sparked backlash in China, where the probe is viewed as “politically inclined.” While the probe into EVs has the highest profile, Chinese titanium, plastic components and phosphate chemicals are likely to become subject to tariffs on the Single Market as a result of five new inquiries aimed at addressing the Chinese distortions the Commission launched since June 2023.

Additionally, the EU has undertaken concrete efforts to bolster its economic security and “de-risk,” rather than “decouple,” its economic relations with China. These efforts go beyond a simple search for a trade rebalance. For example, in October 2023, the Commission called for a risk assessment of critical technologies for the EU’s economic security, namely advanced semiconductors, artificial intelligence, quantum, and biotechnologies. This was an important deliverable of the joint communication of the Commission and the European External Action Service regarding the European Economic Security Strategy, which called for closer scrutiny over technologies that carry a “risk of civil-military fusion.” While China is not explicitly mentioned in the document, it is clear that this measure would effectively slow down the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry (MFA) statement issued after the Summit asserts that, “China opposes the violation of the basic norms of the market economy and opposes politicizing economic and trade issues or over-stretching the concept of security.” For Beijing, the EU’s risk reduction measures share similarities with an even more assertive approach to economic security adopted by Washington. Additionally, the actions taken by the EU create numerous points of friction in the relationship with China and pose obstacles to the country’s economic stability, especially in the context of its economic downturn. Beijing’s defensive attitude towards the EU’s economic security policy further constricted the space for resolving the economic tensions during the Summit.

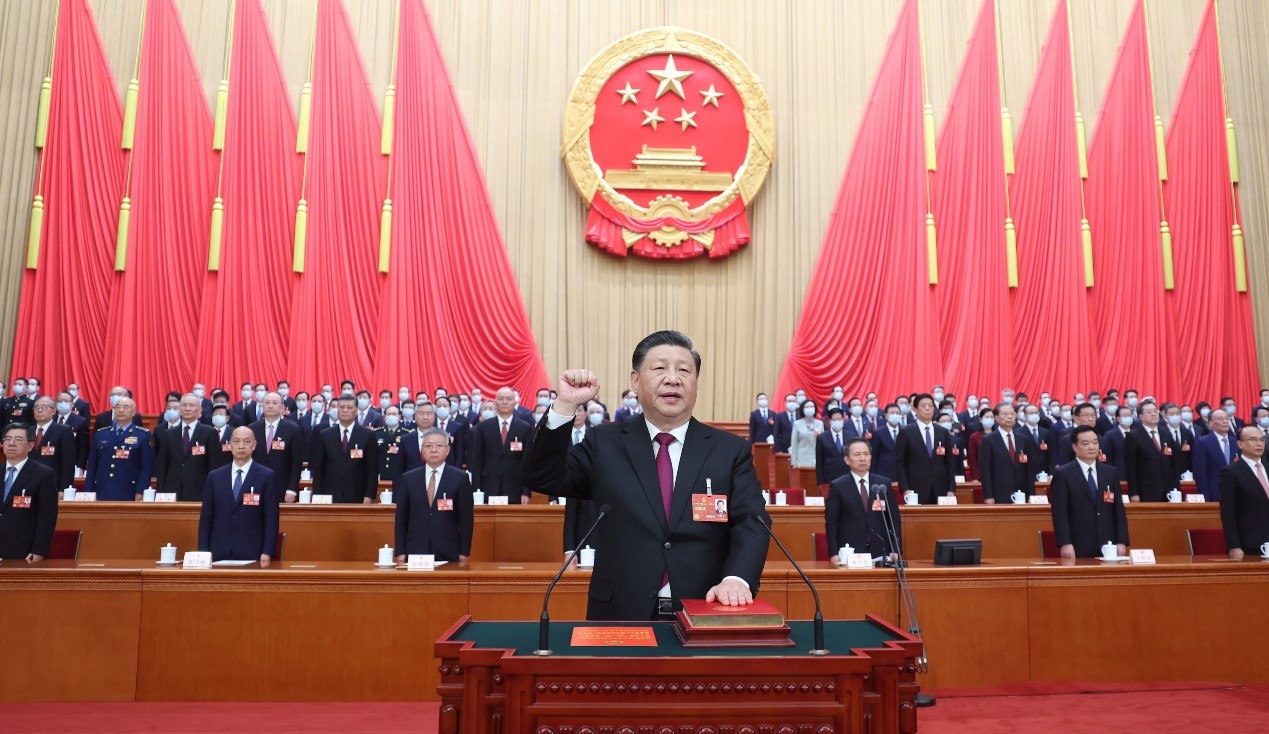

‘China Has a Special Responsibility’: Beijing-Moscow Axis and the War in Ukraine

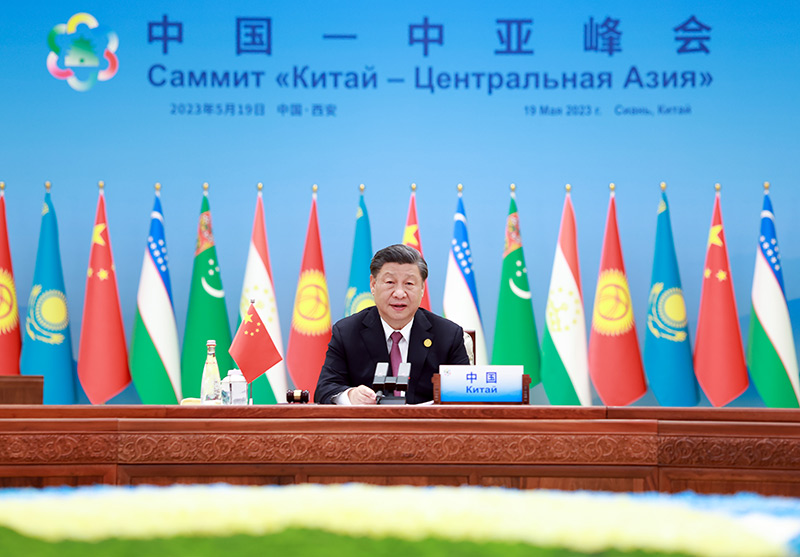

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it initiated the largest war in Europe since World War II. Unsurprisingly, the EU recognized the war on Ukraine as “the most serious security crisis in Europe in decades,” leading to “the EU’s geopolitical awakening.” While China has sought to position itself as a neutral broker in the war, the growing confluence of strategic interests between Beijing and Moscow is increasingly conspicuous. The “no limits partnership” announced by Xi and Putin effectively has enabled the Kremlin to continue its aggression against Ukraine, complicating the efforts of democratic states to isolate Russia and exclude it from the global economy.

China has been instrumental in helping Russia evade international sanctions. Beijing has been able to buy Russian oil (Russian exports of liquefied petroleum gas to China doubled between 2021 and 2022), and Chinese companies have provided the Kremlin’s military with dual-use equipment such as drones and microchips. While China has not officially transferred lethal aid to Russia, leaked Pentagon documents revealed in April 2023 that China’s Central Military Commission had “approved the incremental provision” of weapons and wanted to disguise them as civilian items. Beijing has also been a crucial source of high-tech components with military applications, including avionics and fighter-jet engine parts.

A serious concern for the EU (and its member states in Central and Eastern Europe in particular), China’s tacit support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a major item on the summit’s agenda. Recognizing China’s “special responsibility” as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, Council President Michel called on Beijing to “not supply military tools to Russia” and reiterated the importance of “China’s help to prevent Russia from circumventing sanctions.” Yet, Beijing remained taciturn. The Chinese MFA statement fully omitted the discussion of the Russian war. Therefore, there is no sign that Brussels successfully convinced Beijing to reduce its backing of Moscow.

The Path Forward

The Summit yielded limited outcomes as both parties failed to generate practical ideas for bridging the gap between their positions on critical bilateral and international issues. No joint statement was issued, which aligns with the pre-event announcements. This further demonstrates that Beijing and Brussels did not manage to reach a consensus on effectively addressing issues related to European companies’ access to the Chinese market or Beijing’s tacit support of Putin’s regime during the war in Ukraine. The EU showed its readiness to engage with China on less sensitive topics, such as civil society and cultural cooperation, which is evident in the relaunch of the High-Level People-to-People Dialogue (HPPD). Simultaneously, the EU’s concerns about Beijing’s unfair trade practices and increasing assertiveness in the region, coupled with China’s perception of the EU as increasingly protectionist, pose persistent challenges without a clear pathway toward resolution.

The intra-union complexities further complicate the relationship between Beijing and the EU. The bloc faces ongoing challenges in establishing a cohesive approach toward China. While von der Leyen is resolute in diminishing the EU’s reliance on China through various risk-reducing policies, these endeavors risk encountering obstacles from member states concerned about potential economic repercussions from China’s reaction (e.g., Germany, Spain) or those closely aligned with Beijing’s authorities (Hungary). This dynamic restricts the scope for constructive interaction between the EU and China. Following the 2024 European Parliament elections, the new Commission must address these critical issues promptly and comprehensively.

(Marcin Jerzewski is Head of Taiwan Office, European Values Center for Security Policy.)