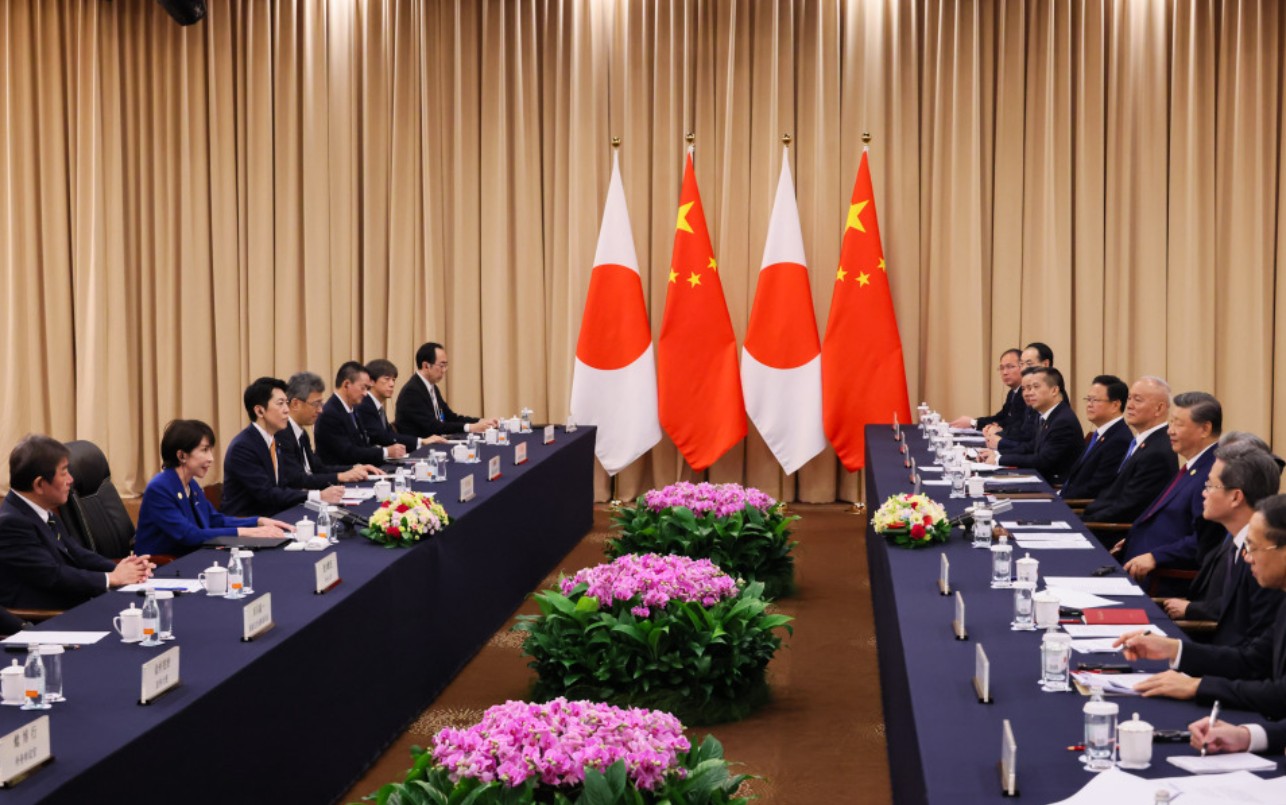

One month after Shangri-La Dialogue, we witness a deterioration of the South China Sea row between China and the Philippines. On June 17, what is arguably the most serious fracas took place between the two rivals around the Second Thomas Shoal. Picture source: The International Institute for Strategic Studies, June 1, 2024, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/iiss_org/53760654311/in/album-72177720317474482/.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 36

The 2024 Shangri-La Dialogue and its Aftermath

By Collin Koh

It is a month since Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD) concluded. A premier Asian security summit, SLD is famous for the diverse set of topics about regional security that forms the annual agenda since its inception in 2002, and of course, high-level representation by the participating countries’ top defense policy elites. The public plenaries grabbed the headlines since they are public — the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS) assiduously makes it a point to even livestream the main plenaries online, and made the transcripts for all these proceedings available, an especially useful service for those who could not attend the Dialogue.

Yet one may get easily carried away by the public speeches made by the various luminaries. This year, besides the usual attention spotlighted on the American and Chinese defense chiefs, eyes were mainly on the keynote address by Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos Jr. Interest in the Philippines at SLD goes back to at least 2016, slightly over a month ahead of the monumental release of the arbitral award on the South China Sea. The anticipation of the conclusion of Manila’s three year-long legal odyssey against Beijing had seized the agenda during that iteration of the SLD. Likewise, given this nostalgia seemed to have been felt this time with Marcos Jr.’s speech – and understandably so again, the spate of South China Sea tensions between China and the Philippines raised the spectre of potential conflict.

SLD as a key platform

The public rhetoric that stemmed out of those speeches and the ensuring question and answer sessions constitutes more than just theatrical symbolism. In a way, the various luminaries made full use of SLD to posit themselves and their national agendas, and directly or indirectly discredit their rivals. Why not? SLD remains a premier regional security summit that is well-attended by key policy elites, and there has always been extensive international media coverage. Even Beijing found that out somewhat in the recent years; the experimentation of its answer to SLD, the Xiangshan Forum (now called Beijing Xiangshan Forum) has so far never been able to match in terms of scale, discussion scope and international prestige. This was one of the key reasons why, after a long hiatus, Beijing decided to reinstate the attendance of the Chinese defense minister.

How poignant that then minister Wei Fenghe, who created a deep impression with his hard-hitting speech and candid demeanor during the Q&A session in 2022, is lately embroiled in a corruption probe alongside his successor Li Shangfu. Incumbent minister Dong Jun did not create any more extraordinary impression compared to Wei, though his speech was laced with more fiery rhetoric especially directed towards Taiwan. The international media seized on the rhetoric, with some commentaries even going as far as arguing that war over the Taiwan Strait is in the offing. Though, one really needs to distinguish between public rhetoric and the realities of policy actions.

What was not as well reported of course, even though it did seize media headlines until Dong’s speech, had been the sideline meetings between the Chinese and American defense chiefs before the SLD main plenaries. Sideline meetings of SLD, one may argue, might have been even more valuable than the public sessions. This meeting appeared to have built on the original consensus reached between U.S. President Joseph Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping over the course of their virtual and in-person summits, especially following the February 2022 spy balloon incident. And not long before SLD, the Chinese and U.S. militaries held their first Military Maritime Consultative Agreement talks in Hawaii since December 2021, following Beijing’s suspension of military-to-military exchanges after then House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022. And not to mention the slew of high-level exchanges between China and the U.S., especially over climate, trade and fentanyl issues.

One month after SLD

So, what happened since? In a span of a month, we witness a deterioration of the South China Sea row between China and the Philippines. On June 17, what is arguably the most serious fracas took place between the two rivals around the Second Thomas Shoal which saw Chinese coastguards resorting to violent means to interdict the Filipino resupply mission – using bladed weapons, engaging in deliberating ramming of vessels, boarding and inspecting the Philippine naval dinghies, seizing Filipino firearms and damaging the boats, as well as hindering the evacuation of a severe Filipino casualty (the loss of a thumb was the worst such injury compared to the casualties sustained during Chinese water cannon attacks on earlier resupply runs). Manila released chilling video footages which showed Chinese coastguards right alongside the Philippine outpost Sierra Madre on the shoal itself, an unprecedented development.

Philippine restraint could be credited for preventing the escalation of this incident. Manila was not keen to blow up the matter, even though notably there was a initial silence in the immediate aftermath and it was the Chinese who first publicized the fracas. Internal confusion and shock over what is deemed a rather unprecedented clash might have caused this delay. But most notably has been the dissonance between Philippine officials in describing the incident – from first calling Chinese actions as “probably an accident or misunderstanding” to later backtracking from this statement altogether. Even though the Marcos Jr. administration continued to indicate no backing down on the Philippine stance, the “primacy” of diplomacy in tamping down feverish-high tensions with Beijing has also been emphasized.

To be sure, it is plausible that none of the parties, China included, wished for a premeditated armed conflict in the South China Sea. But in this case, the American calculus might have loomed large in the background. True to its usual form, there was no lack of public statements streaming out of Washington declaring its ironclad alliance commitment to Manila. And we might expect more joint military exercises in the offing – as a show of force and resolve to Beijing. Yet, there is no further indication of a more robust response in support of the Philippines. Manila even clarified that at this point, there would be neither a need to invoke the Mutual Defense Treaty, nor require foreign assistance for the resupply missions to Second Thomas Shoal.

The somewhat muted response from Manila, which is understandable, could not solely be attributed to Philippine interest. In a huge way, the Philippine calculus on Second Thomas Shoal is also very much dependent on the Americans, given the yawning power asymmetry with China. If Washington could not offer any more robust, tangible support beyond just verbal statements expressing solidarity and perhaps muscle-flexing military exercises, there is no reason to expect Manila to undertake bolder steps that would allow it to more effectively counter Beijing’s actions that undermine its legitimate sovereign rights in the country’s exclusive economic zone. To invoke the MDT or otherwise, both Manila and Washington have to attain consensus. With its hands full dealing with the crisis in Gaza, and protracted war in Ukraine, Washington does not appear to have the stomach for a third front.

Red lines and guardrails

All in all, clearly, as a complex game of mostly competition laced with some tangible forms of cooperation continues to characterize the fractious Sino-U.S. relationship, one expects the rivalry to manifest in such flashpoints as the South China Sea — in this case, the Second Thomas Shoal row between China and the Philippines. The SLD public rhetoric notwithstanding, it appears that at least the current détente between China and the U.S. still held, even if precariously due to the prevalence of many outstanding, unresolved issues. The Biden-Xi consensus remains valid, even if both Great Powers continue to seek ways to out-maneuver against each other and jockey for more advantageous positions. The June 17 incident, barely a fortnight after SLD concluded, is as much a crisis as an opportunity for Beijing to test Washington’s “red-line,” even if the so-called “commonsense guardrails,” first coined by Biden during his meeting with Xi in late 2022, held up.

So, while the world may heave a sigh of relief that things did not further worsen significantly between China and the U.S. over the recent months, there is still reason to worry. There is no reason to believe China wants a full-scale conflict with the Philippines that would risk dragging in the Americans. But Washington’s reticence about being embroiled in a new Indo-Pacific conflict, especially given presidential election is less than six months away, practically endows a wide room of flexibility for Beijing to pursue non-war options in pursuit of its claims in the South China Sea. So it is worrisome for regional peace and stability, if China overplays this berth of flexibility, one might expect an inadvertent conflict to erupt.

Therefore, Washington needs to make clear to Beijing that seeking détente should not be solely for the sake of it; “guardrails” also include China exercising sound judgement and calculations on the complex, evolving situation in the regional flashpoints, not least in the South China Sea. Otherwise, the U.S. risks losing its credibility as a security partner or ally of choice for countries in the region, especially the Philippines.

(Collin Koh is senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, based in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.)