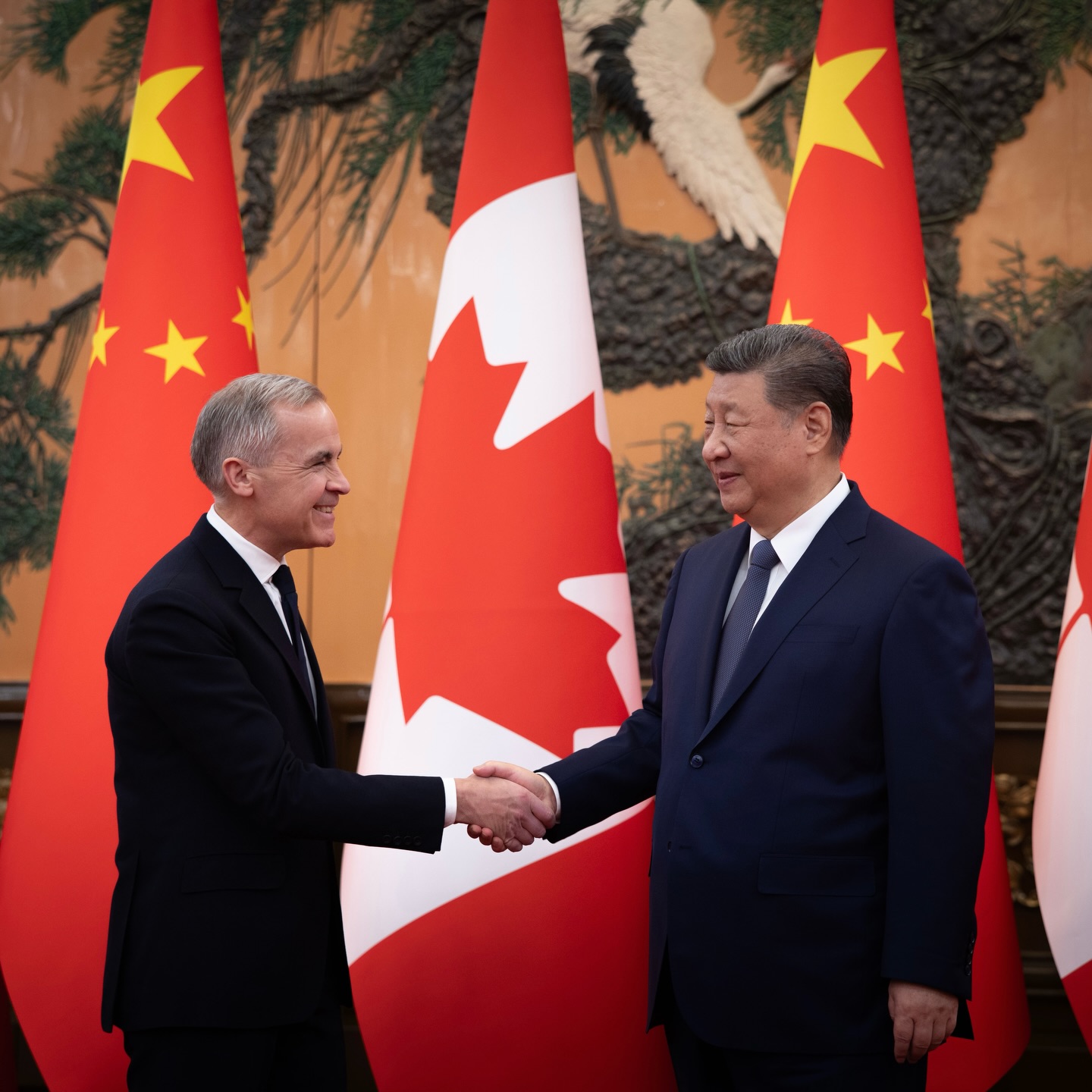

This translates into a nuanced situation for PRC. Subi Reef’s relative distance to Thitu Island means an extra outpost on Sandy Cay becomes a superfluous luxury that needs to be paid with no small amount of political premium for little strategic utility. Picture source: CCTV.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 31

Narrative-Building Trumps Island-Building for Beijing in Sandy Cay

By Collin Koh

Since the last major altercation at Sabina Shoal in August 2024, the South China Sea flashpoint between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Philippines has since shifted to a persistent PRC maritime presence off the Philippine coast, especially Zambales where China Coast Guard vessels in particular have been challenged by their Filipino counterparts. Overall, the situation, while tenuous, has yet to become incendiary.

One could argue that since the June 17, 2024, clash at Second Thomas Shoal, the situation has stabilized somewhat. The July 2024 “provisional arrangement” held on, with the Philippines conducting successful rotation and resupply missions to the BRP Sierra Madre without incident since. There were some flareups over Scarborough Shoal, where Filipino fishers escorted by the country’s maritime patrols were regularly challenged by PRC forces. Otherwise, there had been no major incidents.

Until an uninhabited sandbar in the Spratly Islands, known as Sandy Cay, became a new point of contention.

The Sandy Cay Gambit

Claimed by the Philippines, Vietnam, the PRC and Taiwan, Sandy Cay is located close to Thitu Island (known as Zhongye Dao in China and Pagasa in the Philippines) which measures approximately 0.41 square kilometers, located 227.4 nautical miles (nm) from Palawan and 502.1 nm from Hainan. As its largest claimed terrestrial feature in the Spratlys, where it also hosts a military outpost and a small resident population, Thitu Island amounts to a major strategic interest to Manila.

The occupation of Sandy Cay, therefore, could pose a serious direct threat to the Philippine outpost on Thitu Island. Following a spate of tensions at the feature, including PRC harassment of Filipino forces in January, in April China Coast Guard (CCG) personnel landed on the feature and displayed the PRC flag in a demonstration of sovereignty before they withdrew. This was erroneously reported in the media as Beijing’s “seizure” of Sandy Cay. Seizure would have to mean either Beijing physically occupies the feature, or exercises de facto control to prevent Filipino access.

Neither scenario happened, for not long after PRC personnel landed ashore, their Filipino counterparts landed on Sandy Cay and displayed the Philippine flag in a mark of Manila’s sovereignty over the feature before they also withdrew. Though PRC forces were stationed close to the sandbar, there were no observed attempts to obstruct the Filipinos from this act. Barely a month later, Beijing seemed keen to demonstrate control over Sandy Cay by harassing Philippine government vessels conducting marine scientific research in the area.

Questionable Strategic Utility

Despite the repeated harassments of Filipino forces at Sandy Cay, there are probably no compelling reasons for Beijing to occupy the feature. So far, the artificial island built on Subi Reef, where PRC maintains a major military outpost, could also have facilitated a forceful Chinese takeover. But the strategic utility of so doing is questionable. If the objective is to directly threaten the Filipino outpost on Thitu Island, Sandy Cay in its current physical form does not suffice. Despite being a high-tide feature, PRC would need to build an artificial island capable of sustaining a long-term outpost. But there is already a major outpost in Subi Reef just close by within comfortable striking range. making an extra outpost redundant beyond just serving as a strategic nuisance simply to irritate Manila.

Politically, seizing Sandy Cay could inflict more cost on Beijing. The first is that given Hanoi also claims the feature, PRC authorities plausibly desire not to complicate the situation by seizing it. More generally, Beijing could risk blowing its own narrative about being a constructive and peaceful player in the South China Sea and thereby potentially alienating allies within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), some of whom are also claimant states in the Spratlys. By not seizing Sandy Cay, PRC could keep ASEAN allies and Vietnam on its side and continue to isolate the Philippines from the pack — like what it has been doing since flareups over Second Thomas Shoal in particular erupted from February 2023.

There is also a legal dimension to this problem. The seizure of Sandy Cay could prove to be a last straw for Manila, which has so far not followed through its threat of a new legal suit against Beijing. If PRC forces seize and permanently occupy Sandy Cay, it could galvanize the Philippines to initiative new international arbitral proceedings, one that could potentially be joined by Vietnam as well.

Superfluous Luxury

All in all, this translates into a nuanced situation for PRC. On the one hand, Subi Reef’s relative distance to Thitu Island means an extra outpost on Sandy Cay becomes a superfluous luxury that needs to be paid with no small amount of political premium for little strategic utility. On the other hand, there is no reason for Zhongnanhai to give the impression that it has relinquished its claim to Sandy Cay and risk domestic political blowback by rolling back on coercive acts against the Filipinos at the feature.

From a geographical and operational perspective, the PRC artificial island on Subi Reef alone, given its overpowering size relative to Thitu Island, suffices to directly pose a physical threat to the Filipino outpost, be it through missile/drone or air strikes. Yet given the distance, at slightly more than 20 kilometers, Subi Reef is farther away from Sandy Cay than Thitu Island is, thus conferring the Filipinos a little geographical advantage in backstopping its physical assertion moves on the feature. Further incendiary PRC moves, such as physical occupation of Sandy Cay, could become grounds for justification by Manila to further beef up its presence on Thitu Island.

To complicate matters, should Manila involve Washington, Filipino (and potentially American) forces could monitor the newfound PRC occupation of Sandy Cay from the Thitu Island vantage point, and potentially disrupt island construction and militarization activities on the sandbar given the close proximity.

Therefore, fears of Beijing creating a new status quo in the Spratlys by “seizing” Sandy Cay could have been overexaggerated. At present, ASEAN has largely been either ambivalent or disapproving towards Manila’s more assertive pushback against the PRC in the South China Sea, with some of the Southeast Asian policy elites criticizing the Filipinos for unnecessarily provoking Beijing and worsening tensions in the area. It is likely that the PRC will seek to maintain this situation of making the Philippines an outlier of ASEAN. Seizing Sandy Cay could reverse these important strategic gains which amount to continued division within ASEAN, effectively paralyzing the bloc from achieving any united position on the South China Sea disputes.

In the long term, maintaining a viable strategic narrative, not a new outpost on a feature of limited strategic utility, would serve Beijing’s interests in the South China Sea. It would continue to harass Philippine forces at Sandy Cay at a time and context of its own choosing as and when politically expedient to do so, but not more than that.

(Collin Koh is senior fellow at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.)