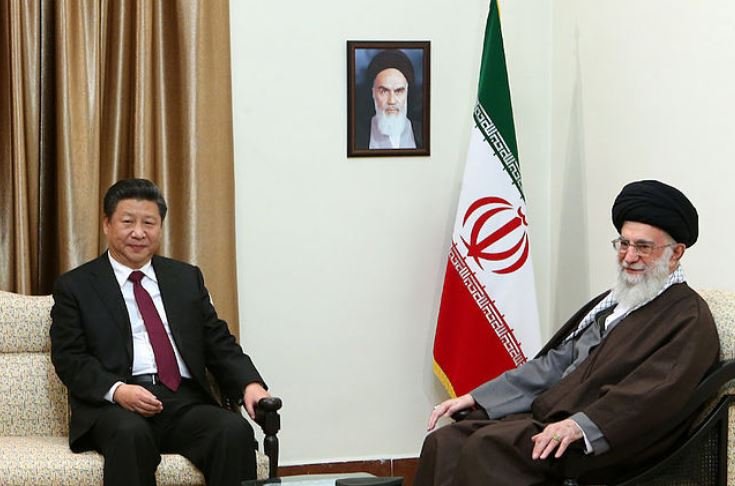

China has numerous economic and political connections to Iran and is a major purchaser of Iranian oil despite U.S sanctions. Iran is a key partner for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It recently joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the two countries have concluded a 25-Year Strategic Cooperation Agreement.

Picture source: AIC, March 2, 2022, AIC, <http://www.us-iran.org/resources/2022/3/1/media-guide-the-iran-china-strategic-partnership>.

Unrest in Iran and the Future of Iran-China Relations

Prospects & Perspectives No. 63 November 2, 2022

By William Figueroa

Iran is currently being rocked by a series of popular protests sparked by the death of 22-year old Mahsa Amini last month, who was in the custody of Iran’s “morality police” for wearing an “improper” hijab. Reports of her brutal treatment led to an outcry against Iran’s repressive social policies aimed at women, and have led to riots and calls in some cities to overthrow the government and replace it with a secular Republic of Iran.

Chanting “women, life, freedom” as they clash night after night with security forces, thousands of Iranian women are casting off their rusari (headscarves) and, together with an equally large contingent of Iranian men, are confronting the state head on. Fueled by widespread economic instability, it is the largest popular challenge to Iran’s theocratic regime since its inception in 1979, with demonstrations held in at least 125 cities. Security forces have been swift and brutal in cracking down on dissent; at the time of writing, organizations like Human Rights Activists in Iran claim at least 270 people have been killed and at least 14,000 detained. The future of the protests is unknown; it does seem like a barrier of fear has been broken, but have not become the kind of truly mass protests that overthrew the Shah in 1979, and the government has so far seemed to be able to weather the storm.

China’s reaction to the situation has been predictably muted. Reports of the unrest are almost entirely absent from Chinese state-controlled media. Some incidents likely related to the unrest, like an attack on a police station in Zahedan on October 30 by unnamed armed separatists, have been reported, but only including the government’s perspective and without reference to the ongoing unrest. Given Iran and China’s close diplomatic relationship, this is not surprising: China has numerous economic and political connections to Iran and is a major purchaser of Iranian oil despite U.S sanctions. Chinese leader Xi Jinping met with Iranian President Raisi on September 16, the exact day that the riots began in earnest, and welcomed Iran’s role in China’s global development and security initiatives. Iran is a key partner for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It recently joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the two countries have concluded a 25-Year Strategic Cooperation Agreement. Although there have been numerous complications to implementing the deal, and Iran remains a lower priority destination for Chinese FDI and business ventures than its neighbors, it remains part of China’s global strategy of engagement and an important strategic and economic relationship in the Middle East.

There is also evidence that Chinese companies are the main source of the surveillance and internet censorship technologies that are enabling the Iranian government to catch and punish those who participate in the unrest. Chinese company Tiandy, which has previously provided surveillance equipment for the Malaysian police, has a documented relationship with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC) and most likely provided them with the surveillance cameras with facial recognition technology that are currently being used to identify protests. Iran also closely cooperates with China in the construction and training for administration of its telecommunications network. It has also repeatedly shut down the internet across the entire country and banned the use of previously popular social media apps like Instagram and Whatsapp, moving internet censorship in Iran closer to what reformist newspapers are calling “Chinese-style internet filtering.” It is highly likely that the technology to do so — and the training to use it — came from China.

There is little ideological or practical reason for China to break its silence on the protests. It is unlikely to see them through as positive a lens as Western governments do. More likely, they see them as the Iranian government does, as either a plot supported by foreigners or a political challenge similar to the Arab Spring or the Color Revolutions of the early 2000s. Chinese officials have historically seen foreign revolutionary movements as a kind of warning or negative example for China to learn from, and are anxious to prevent the spread of such popular movements elsewhere. This is especially true in Islamic countries and countries close to the border with Xinjiang, for obvious reasons.

There is also little reason for Beijing to preemptively support the movement in the event that the government falls. First of all, the protests have not reached a point where that outcome seems likely at the present time. Second, China supported the Shah’s government until the last possible moment, and while the Islamic Republic was initially cold towards Chinese overtures as a result, they quickly re-established relations when they needed to purchase Chinese weapons during the Iran-Iraq War. Thus, the lesson likely drawn was that it would be better to support the current government, as even if there is a change of the guard, the material and political benefits of working with China will outweigh any hurt feelings.

Iran is not China’s only or even most significant partner in the region. China’s relationship with Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council are all deeper, more substantial, and probably more strategically significant to China’s global economic, diplomatic, and development strategy. Relations with Iran are in fact held back substantially by the need to balance against these countries, all of which oppose the expansion of Iranian influence, as well as China’s relationship with the United States. However, the relationship with Iran is still important enough not to jeopardize by careless commentary, and in any case, there is little sympathy for the protesters among Chinese elite.

Interestingly, this is not true of the Chinese population. Images and news of the riots were widely shared and commented on in Chinese social media, and a great deal of sympathy and support for the protesters was expressed. Some Chinese netizens have also expressed surprise that Iranian media is reporting on such events, as press freedoms are even more restricted in China. It remains to be seen whether such protests, whether in Iran, Russia, or elsewhere, will inspire similar actions in China. But for now, it seems unlikely that the unrest in Iran is going to substantially impact Iran-China relations.

(Dr. William Figueroa is a Research Associate at the Cambridge Centre for Geopolitics.)