Toward a Contested World: Observations on the Shangri-La Dialogue 2022

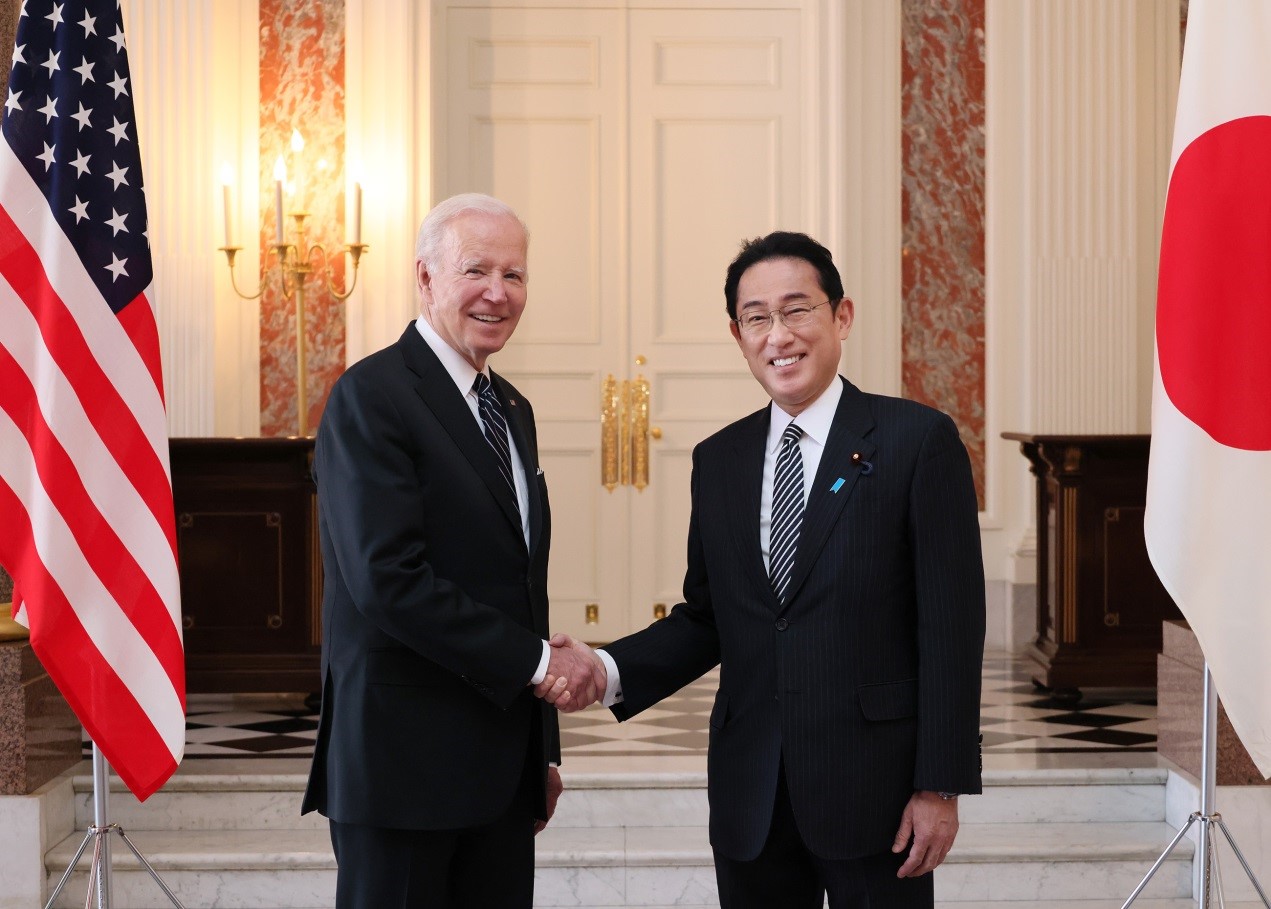

If the 2022 Shangri-La Dialogue provides a snapshot of the current state of the world, then it is unsettling in their familiarity. The world seems to be seeing a reversion to the major power contestation and outright wars of aggression common in the past. Coupled with widespread economic disruption and a lingering pandemic, there is good reason to expect continued global upheaval. Picture source: U.S. Secretary of Defense, June 10, 2022, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:2022_Shangri-La_Dialogue?uselang=lzh#/media/File:220609-D-TT977-0272_(52134650582).jpg.

Prospects & Perspectives 2022 No. 39

Toward a Contested World: Observations on the Shangri-La Dialogue 2022

By Ja-Ian Chong

June 2022 saw the return of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore following a two-year, COVID-induced suspension. In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the event marked the continued solidification of a distinction between the United States and its allies on one side and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Russia on the other. Such circumstances create a narrowing space for the many states that are still seeking to navigate between Washington and Beijing. The ongoing war in Ukraine and tensions in East Asia brought repeated discussions about Taiwan as a potential flashpoint during the proceedings, but Taiwan’s own voice in the matter was noticeably absent. If nothing else, the 2022 edition of the Shangri-La Dialogue may well represent the persistence of the growing antagonism between the PRC and the United States and its close allies.

Whose Rules? What Order?

A constant refrain during this latest iteration of the Shangri-La Dialogue was a need for a stable rules-based order. For the U.S. and its NATO allies in Europe as well as its major Pacific allies, Australia, Japan, and South Korea, this clearly meant major power restraint through international law and institutions as currently constituted. The undergirding position was a conviction that the Russian invasion of Ukraine is an unacceptable affront to the international system not to be repeated anywhere else, including toward Taiwan. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Commander Admiral John Aquilino underscored that the order Washington is trying to uphold seeks to provide the basis for states in the region to avoid a need to make hard choices among major powers. The closing of ranks among North American, European, and Asian partners is remarkable to observe and articulates more outward consistency than even the response to the terror attacks of 9/11 two decades ago.

Washington and its key allies appeared to make a conscious effort to avoid over-emphasizing their shared democratic values, a quality they previously highlighted. Such caution reflects a tension facing current U.S. strategy. Underscoring a common commitment to democracy is important for alliance management—there is otherwise no natural reason why security concerns facing France or Germany should matter to South Korea or Japan or vice versa. Yet, overplaying the defining democratic characteristic of the U.S.-led global alliance can be alienating for important potential partners whose autocratic tendencies make them view political liberalization as an existential threat. Addressing this bifurcation in preferences is likely to remain a critical challenge for the U.S. and its allies to handle. Doing so effectively also means avoiding the types of unwelcome references to colonial history made by some European officials, which chafed against sensibilities across much of Asia.

For its part, the PRC also stressed its commitment to rules and order, while seeking to question the approach to these issues adopted by the United States and its allies. General Wei Fenghe, the PRC Defence Minister, used his keynote speech to ask why it is that only some freedoms and rules seemed to matter to Washington and its allied governments. For Beijing, the order and rules seemed predicated on an idea of sovereignty that limited supranational jurisdiction in ways that freed states to pursue what they interpreted to be in their national interest. The PRC position further pointed to initiatives by the United States and its allies as “Cold War thinking” and efforts to establish an “Asian NATO” that would undermine regional stability, just as NATO supposedly provoked Russia’s attack on Ukraine, in Beijing’s estimation. The PRC’s position appeared to have been designed to spark anxieties about stability and regime change among the majority of regional states that are not closely aligned with the United States a moment of significant global uncertainty.

Other national delegations appeared wary of the contestation between the PRC and the U.S. and its allies. Officials from Indonesia and India to Fiji were keen to remind participants of their prioritization of cooperation, borrowing from Nelson Mandela to state that the “enemy” of another is not necessarily their own adversary. Indonesia’s defense minister and presidential hopeful, General (retired) Prabowo Subianto, further took his remarks as an opportunity to raise Indonesia’s “Asian” culture that presumably distinguishes it from some idea of an incompatible “West.” Statements such as these reflect the growing discomfort of states that wish to continue enjoying the best of all worlds from working with both the PRC and the U.S.-led system at a time when overlapping interests between the two sides may be diminishing. Nonetheless, PRC representatives appeared sufficiently uncomfortable at the volume of pushback from the United States and its partners for a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) senior colonel to publicly query if the forum intended to have countries “gang up” on Beijing.

Voice and the Shadow of War

Conflict weighed heavily on the last Shangri-La Dialogue, providing the backdrop for almost every other conversation—and unsurprisingly so given Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine. Punctuating this theme was Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s special address, delivered virtually from a secure, undisclosed location in Kyiv. Dressed in a t-shirt designed by a Singaporean teenager to help raise funds for humanitarian assistance for Ukraine rather than his usual olive fatigues, Zelensky drew parallels between his country’s fight and the region’s history of struggle against colonialism. He reminded attendees that Russia’s war in Ukraine contributed to the supply chain disruptions fueling global inflation and food insecurity, which affected regional states such as Indonesia.

Zelensky’s presence contrasted the other potential flashpoint that garnered much attention at the Shangri-La Dialogue: Taiwan. As expected, PRC officials insisted on control of Taiwan, including through the use of force. The United States and its allies, including U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, made it a point to repeatedly dissuade Beijing from provocative action. Unlike Ukraine, however, the expediency of ensuring PRC participation meant that there were no extended remarks to clarify or explain Taiwan’s position as seen by Taiwanese, even if guests from Taiwan were in attendance in an unofficial capacity. This left the gathering less informed about the situation in the Taiwan Strait, possible developments, and ways to mitigate risk as might otherwise be the case. Taipei’s absence leaves more room for potential miscalculation and unintended escalation, regardless of one’s position regarding its status.

Signs of a More Tumultuous World

If the 2022 Shangri-La Dialogue provides a snapshot of the current state of the world, then it is unsettling in their familiarity. The world seems to be seeing a reversion to the major power contestation and outright wars of aggression common in the past. Coupled with widespread economic disruption and a lingering pandemic, there is good reason to expect continued global upheaval. Perhaps the liberal rules-based order vaunted by the United States and its allies or the more state- and raw power-centered version China and Russia offer may provide some paths forward. However, many states in Asia and elsewhere continue to harbor reservations about where either will lead and remain steadfast in their belief of being able to benefit from working with all sides. Such circumstances may potentially create conditions for more intense global competition for their loyalties among the major powers and their established partners, potentially paving the way for greater turbulence. States could do well to prepare for this friction that may lie ahead.

(Dr. Ja Ian Chong is Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, National University of Singapore)