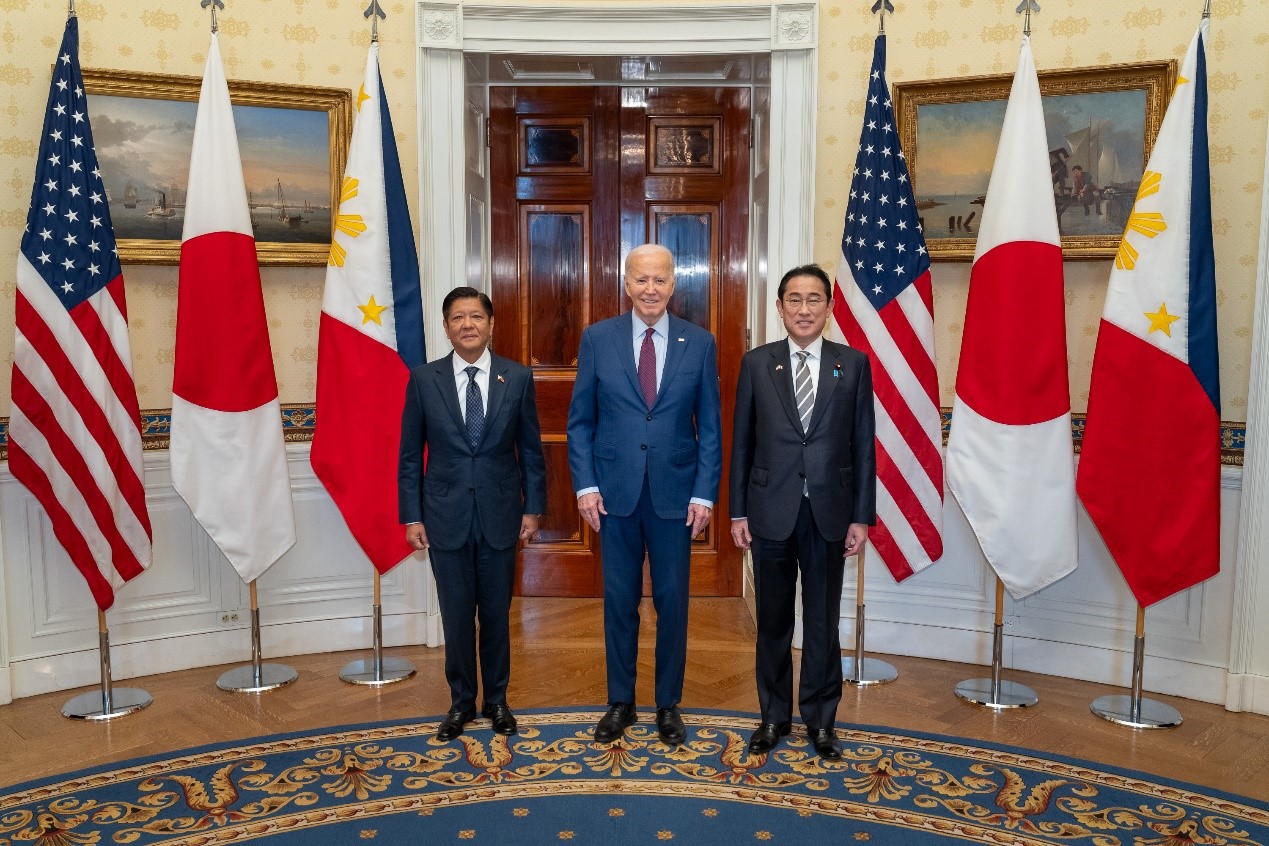

Natural Partners: Advancing Cooperation between Canada and Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific

The peace, security, and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific are fundamental to Canadian interests and values in the region and internationally. If conflict avoidance is truly Ottawa’s goal, then engaging with Taiwan, including on matters of security and defence, is crucial to send a strong deterrent message.

Picture source: Taipei Economic and Cultural Office, Toronto, Taipei Economic and Cultural Office, Toronto, https://www.roc-taiwan.org/cayyz/post/5708.html

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 48

Natural Partners: Advancing Cooperation between Canada and Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific

By A joint Prospect Foundation-Macdonald-Laurier publication

September 28, 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic is proof that what happens on one end of the world can reverberate in Canada as well. We are a part of the global community, as much at risk from existential dilemmas as any other nation, even if Canada’s geographic fortunes make us forget that fact.

In this context, Canada has lagged in formulating a meaningful strategy for engaging with the Indo-Pacific. As a result, Ottawa remains rudderless in its ability to understand and engage with the region, let alone pursue meaningful policy that supports our interests and values in concert with our allies and friends.

The fact is that Canada is an Indo-Pacific country, and the contours of the region are certain to help shape Canada’s future. The region contains the top three countries which new Canadians will immigrate from this year; it hosts four of the worlds’ five largest economies and many of Canada’s largest and most important trading partners; some 60 percent of the world’s population call this pivotal region home.

Furthermore, the region is under immense pressure emanating from the rise of authoritarian China. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seeks to gain strategic advantage in the Indo-Pacific through a combination of economic, political, and in some cases, military means. Nowhere is this revisionism clearer than in the air and in the seas around the Taiwan Strait. Beijing constantly undermines and threatens the democratic self-governance of the 23.5 million people in Taiwan, and this challenge poses an existential threat to the safety, security, and prosperity of the entire region.

Canada has also had a taste for the kind threats and coercive action that China employs to pursue its interests. Most notable has been the hostage diplomacy leveraged against Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, but it is important to remember that China has also engaged in economic coercion efforts and has threatened escalatory action against Canada and its allies for opposing Beijing on all manner of policy issues.

To navigate these threats successfully requires cooperation with partners who share our interests and have endured similar experiences. As Ottawa looks to engage in the region and contribute meaningfully to it, policy-makers would do well to consider the importance of Taiwan as an in-dispensable and nature partner in the region.

This commentary will discuss first Canada’s interests in the Indo-Pacific and the potential avenues for engagement with our allies. It will also highlight the nature of the challenges facing Tai-wan, and how those challenges intersect with Canada’s interests. It will then conclude with recommendations for how Ottawa can improve its approach to the region through a more robust engagement with Taiwan and other countries that share our interests.

Canada’s Interests and Engagement in the Indo-Pacific

Canadian interests in the Indo-Pacific region are based on the fundamental belief about the value of the rules-based international order and the need for likeminded countries to strengthen democracy, promote human rights, expand fair and prosperous economic engagement, manage complex challenges (such as climate change and COVID-19), settle disputes peacefully, and uphold our values as part of the international order. Peace and prosperity alike are thus premised on an inter-national system that creates both space for diplomacy and dialogue and consequences for aggression and revisionism.

As a middle power, Canada can contribute meaningfully to the maintenance of the rules-based international order. But it cannot do so alone; instead, Canada achieves its goals best when working in concert with allies.

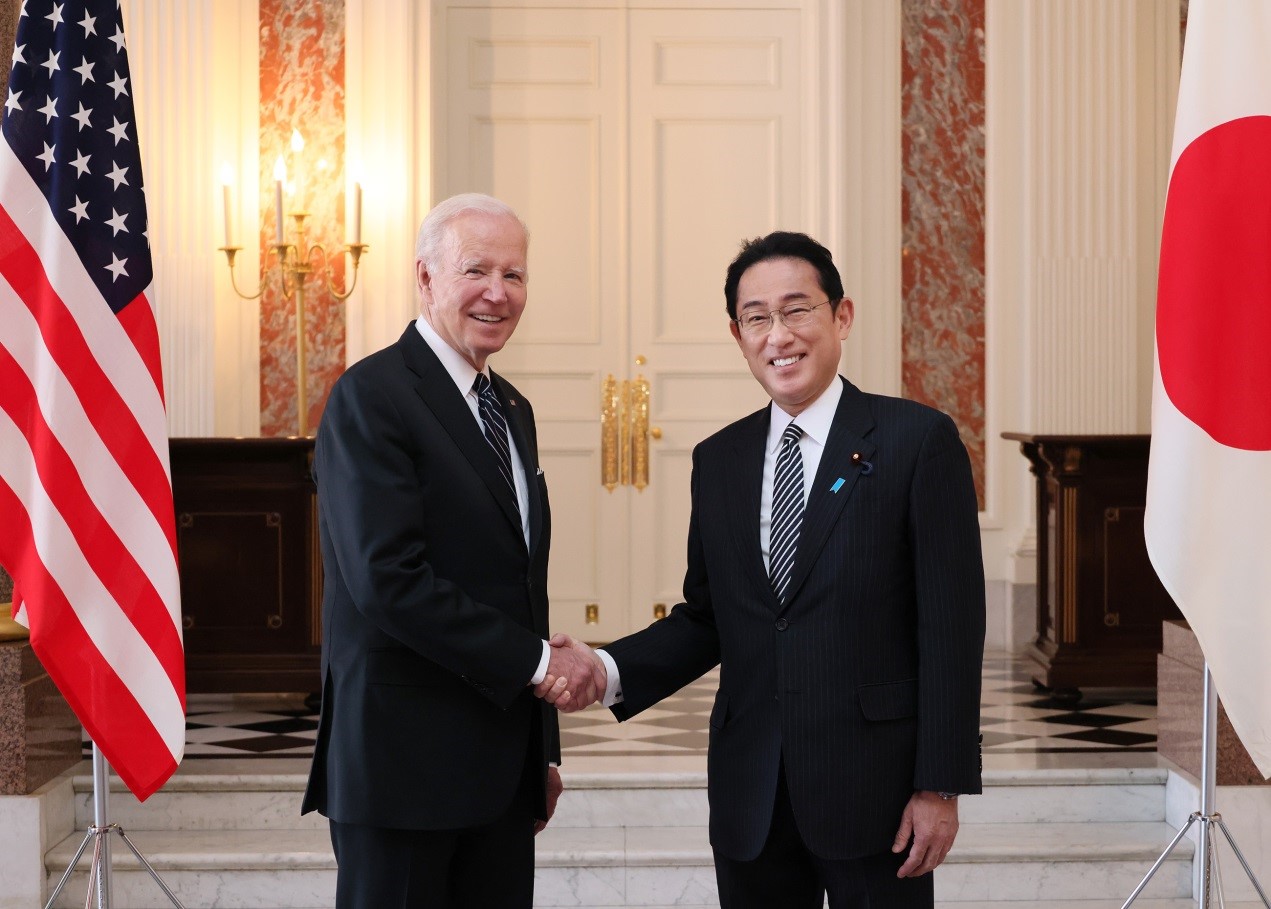

Fundamental to this engagement has traditionally been a framework that aligns with U.S. foreign policy. Canada is intrinsically linked to the United States, as reflected in our trade, defence, and diplomatic ties. Of course, Canada cannot necessarily rely solely on the United States in its approach to global affairs. Our interests may be closely aligned but that does not mean that they are the same. Canada must resist the temptation to simply follow in lockstep with the US on the world stage, even as we seek new opportunities to cooperate with our most powerful ally in the Indo-Pacific.

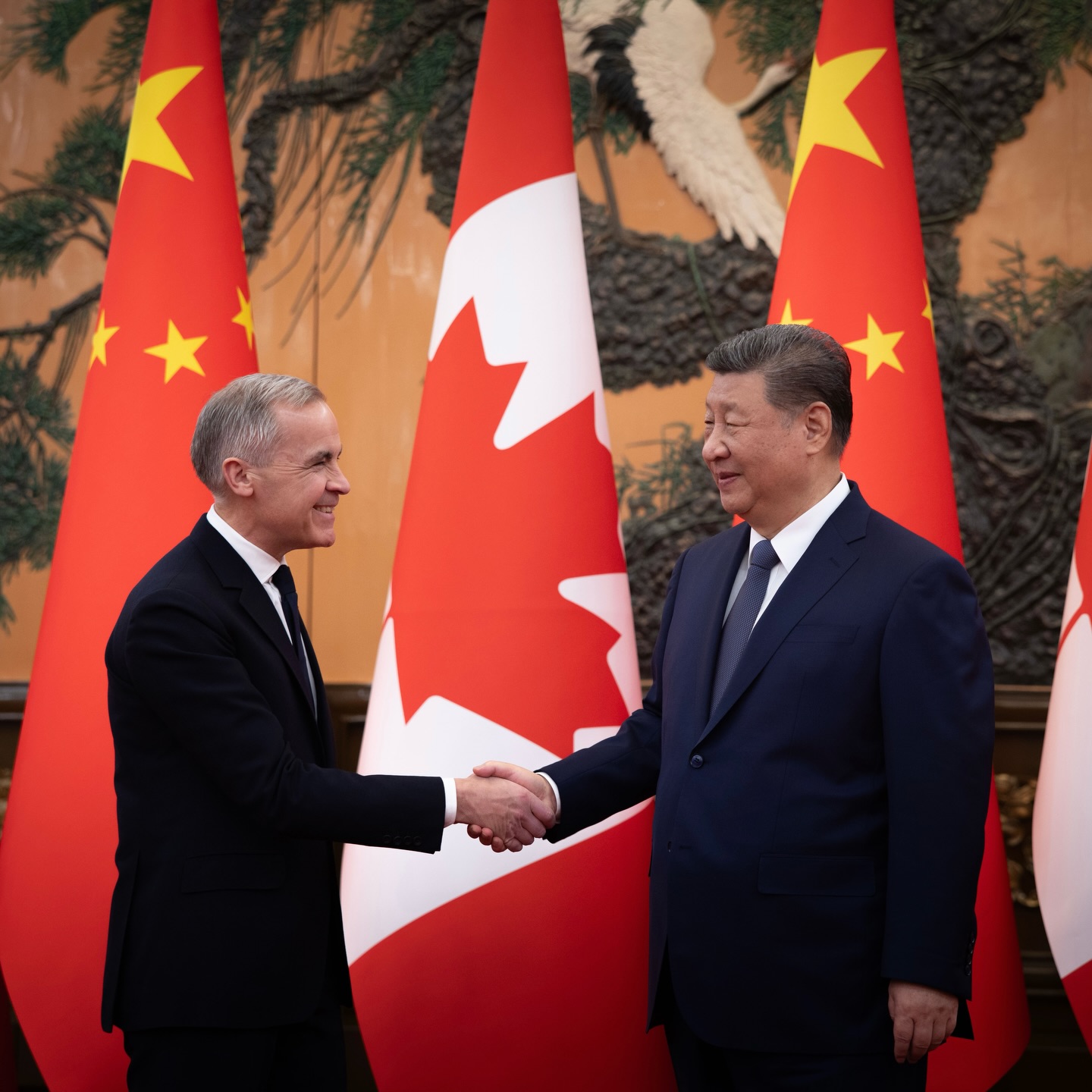

It’s also imperative that Canada reject this notion of a “third path” between China and the United States – a middle road between superpowers that treats them as equal or equivalent partners. Simply put, there is no equivalency between the two powers. Beijing is a fundamentally revisionist power opposed to the interests and values that underpin Canadian foreign policy. Washington is Ottawa’s most indispensable ally with whom we share common cause on the most important global issues.

Canada must also reject the view, common within certain segments of the Canadian government, that sees China as a partner despite its bad behaviour and is risk-averse to the point of inaction on issues of strategic importance involving China. The disruptive role played by China cannot be underplayed anymore, both to ensure that Canada is prioritizing its interests properly and to signal to our allies that Ottawa is a trusted partner rather than a weak link.

Rather than relying on an increasingly mercurial United States or charting a “third path” between Beijing and Washington, Canada must find its own contributions and stake out its own interests in cooperation with our allies. Alignment and cooperation are positive, including where possible with China on issues such as climate change. But alignment should not be an end onto itself, even with the United States, and it should never come at the expense of our core interests and values.

Canada should root its engagement in the Indo-Pacific through cooperation with our allies and partners who share our fundamental belief in the rules-based international order. Where Canadian priorities align with US priorities, it is all the better. And we should also seek to align our approach to the Indo-Pacific as best as we can with U.S. foreign policy. But we also need to be able to stake out a Canadian leadership role independent of any shifting American priorities. Simply put, US involvement should not be a precondition to Canadian participation in regional efforts and cooperation.

To some extent, this has already started to occur. Canada’s participation in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and other trade arrangements, its expanding military exercises, its leadership on sanctions enforcement against North Korea, and its global effort to target arbitrary detention are examples of moves which Canada has staked unique leadership on. This kind of engagement should be increased, expanded, and applied strategically rather than on an ad hoc basis.

The China Challenge, and the Taiwan Solution

Canada needs to invest significantly in a stronger approach to regional engagement. Expanding engagement with countries such as Japan, Australia, and others represent obvious opportunities; they are partners that share interests and values while also presenting little risk for policy-makers. Despite missteps and false starts, Canada’s relationship with countries like India will require steady and predictable investment of time and energy from Canada’s political and diplomatic leadership.

Often absent in discussions of Indo-Pacific opportunity is the clear opportunity posed by Taiwan. Both Canada and Taiwan share common interests in a rules-based world order, and particularly a free and open Indo-Pacific. Indeed, for several reasons, Taiwan is a clear partner for Canada.

The first and most obvious reason for this partnership is necessity. If Canada wishes to contribute to the maintenance of the rules-based international order, then it must also commit itself to the defence of Taiwan, a country that stands at the vanguard of democracy and faces significant threats from China.

In 2021 alone, China has engaged in more clear and provocative violations of Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone than at any point in over 20 years. Military exercises in the region and grey zone intimidation from China are continuing to escalate, as is the CCP’s overt bellicose rhetoric. With heightened pressure in the Taiwan Strait, Canada must begin to clearly define how it will contribute to deterrence. Though unlikely in the short-term, Canada must also seriously think through how it would support its allies and contribute to humanitarian relief if the situation in the Taiwan Strait escalates to military conflict.

More than 60,000 Canadian nationals live in Taiwan, making it one of the most significant Canadian diaspora communities globally. In the event of a crisis, Canada faces a refugee and evacuation challenge on a scale of which policy-makers likely are unprepared. Without formal military or security engagement with Taiwan, Canada is at a clear disadvantage in the event of a crisis.

But Taiwan is far more than just the frontline of the democratic global system. Taiwan is also a useful partner in its own right with much to offer. If Canada is to be serious about finding partners who share our interests and who can anchor our approach to the region, they will find few better partners than Taiwan.

Our economies enjoy significant complementarity with one another. In particular, Canada has access to the strategic resources that Taiwan lacks, while Taiwan manufactures the semi-conductors and computer components that are crucial for any modern economy. In an economic dispute with China, both countries would benefit greatly from the stability provided by one an-other’s economies.

Canada can also learn from how Taiwan has approached some key challenges, including digital governance, managing and combatting disinformation, resisting authoritarian coercion, and of course, the extremely salient area of public health and pandemic management. Ultimately, while engaging with Taiwan (even modestly) will undoubtedly be met with Beijing’s ire, they are well-worth the effort, and Canada has many options on the table to increase engagement even within the confines of a ‘One China’ policy.

A Role within or without the Quad?

Additionally, Canada should explore how it can become more involved with major regional powers, including through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or the Quad). While Canada likely lacks the regional military presence necessary to be a full Quad member, Canada could become a useful addition into any Quad-plus framework. Such a framework would require Canada to provide a unique contribution to justify its presence.

For example, Canada could serve as a significant interlocutor between the Quad and other partners, such as ASEAN, or to individual states like Taiwan that are often excluded from formal participation in multilateral forums. This kind of unique contribution would foster stronger ties for Canada both within the Quad, and with smaller states whose participation in the framework might be more difficult to justify.

Another advantage Canada has is that, unlike these smaller states, Canada is more inoculated from blowback from China, and informal cooperation with the Quad would be seen as less threatening than an outright expansion of membership. Canada is perhaps the perfect country in terms of size and geography to accomplish this interlocutor role, one which could place Canadian interests at the centre of broader strategic cooperation in the region with partners who share our interests.

Moreover, the Quad is branching out. While its previously narrow focus on maritime security was the principal theme of the group, vaccine diplomacy, infrastructure development, investment, and more all now play significant roles. By emphasizing these softer forms of engagement, Canada likely has more openings to make positive contributions to a Quad-plus framework.

By contributing to a Quad-plus framework, Canada may open the door for other countries to collaborate more closely in a greater Quad-related ecosystem. This has the potential to create an informal framework to check China’s ambitions, creating both a deterrent while avoiding an explicit alliance or mutual defence framework that would invite more aggressive backlash from Beijing.

To be sure, the Quad is an imperfect grouping. Mooring Canadian interests under a Quad-plus framework may create new difficulties, as the informal Quad alliance itself experiences its own modest challenges. Moreover, Global Affairs cannot afford to indulge the temptation to over-invest in greater Quad-plus cooperation at the expense of other important multilateral, bilateral, and minilateral efforts. While perhaps lacking the limelight of the Quad arrangement, the day-to-day work on dialogue and diplomacy are fundamentally critical for shoring up regional cooperation, including defence and security cooperation.

In any case, if Canada wants a seat at the table, it needs to invest more into diplomatic and security engagement in the Indo-Pacific region, setting goals that are both reasonable and achievable while establishing a clear ambition to stand up in defence of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. One such goal should be for policy-makers to establish whether a Quad-plus model could offer an anchor point for Canada’s engagement in the region and would be of interest to the existing Quad membership.

Recommendations

As Canada seeks to formalize its Indo-Pacific strategy, they should consider the following policy ideas:

Taiwan

- Support ongoing efforts to allow Taiwan to join multilateral forums, including the CPTPP, Interpol and other UN related agencies.

- Serve as an interlocutor for Taiwan in international bodies to which Taiwan cannot secure access.

- Move Taiwan from under the “greater China division” of Global Affairs to another division that is not limited in its thinking by a narrow interest on Canada-China relations.

- Embrace the modest and incremental changes advocated for in policy proposals such as Bill C-315.

- Identify creative ways to upgrade relations with Taiwan, including through both private and public initiatives and informal avenues.

- Consider joining the Global Cooperation and Training Framework, which fosters dialogue and information exchanges between countries with counterparts in Taiwan.

- Pursue closer cooperation between Canada’s Department of National Defence and Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense, including through Royal Military College of Canada officer exchanges, cadet exchanges, language training and sending Department of National Defence (DND) representatives to dialogues such as the Yushan Forum and forthcoming Halifax Forum that will take place in Taipei.

- Develop interagency cooperation between security and intelligence agencies.

The Indo-Pacific

- Develop a clear Canadian approach and strategy for engaging with the Quad, whether in a Quad-plus framework or otherwise.

- Solidify an Indo-Pacific strategy that invests in regional partners in pursuit of our own interests and abandon the framework of playing as the “third wheel” to US policy or seeking a “third path” between Washington and Beijing.

- Integrate and institutionalize values across issues such as peacekeeping, climate change, international Indigenous rights, human rights, and more as a fundamental component of an Indo-Pacific strategy.

- Strengthen security and military relations with countries in the Indo-Pacific, most specifically Japan.

- Ensure sufficient funding for our diplomatic, economic, and security engagement in the region, including support for a robust approach to public diplomacy to establish Canada as an Indo-Pacific nation.

- Support the creation of a national-level democracy promotion non-governmental organization to expand the breadth and depth of Canadian voices contributing to the conversation on the Indo-Pacific.

Conclusion

The peace, security, and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific are fundamental to Canadian interests and values in the region and internationally. Canada can provide unique contributions to the region, to secure its interests in concert with a wide array of allies. With China posing increasing challenges, it is imperative for Canada to seize upon the myriad of opportunities that exist for cooperation with like-minded allies in the Indo-Pacific region.

Additionally, when it comes to the rules-based international order, Canada has every interest in standing with partners like Taiwan. Abdicating our responsibility toward Taiwan as a fellow democracy is both craven and unpragmatic. Canada must solidify its relationship with Taiwan. Doing so will also ensure that Canada has an anchor for its foreign policy objectives in the region and beyond. Finally, if conflict avoidance is truly Ottawa’s goal, then engaging with Taiwan, including on matters of security and defence, is crucial to send a strong deterrent message.

(This commentary is based on a closed-door roundtable discussion between representatives of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the Prospect Foundation. This roundtable was held under Chatham House rules. No ideas or language in this article represent direct comments or quotations from the event.)