The Return of the Queen? HMS Queen Elizabeth’s Visit to the Indo-Pacific

The purpose of the British carrier group visit to the Indo-Pacific may not have been to provoke conflict, or to participate in conflicts and wars, but rather to jointly perform a deterrence task against Chinese military adventurism. If Britain’s purpose is merely to deter, when China insists on taking military action in furtherance of its core interests, should Britain participate in combat operations?

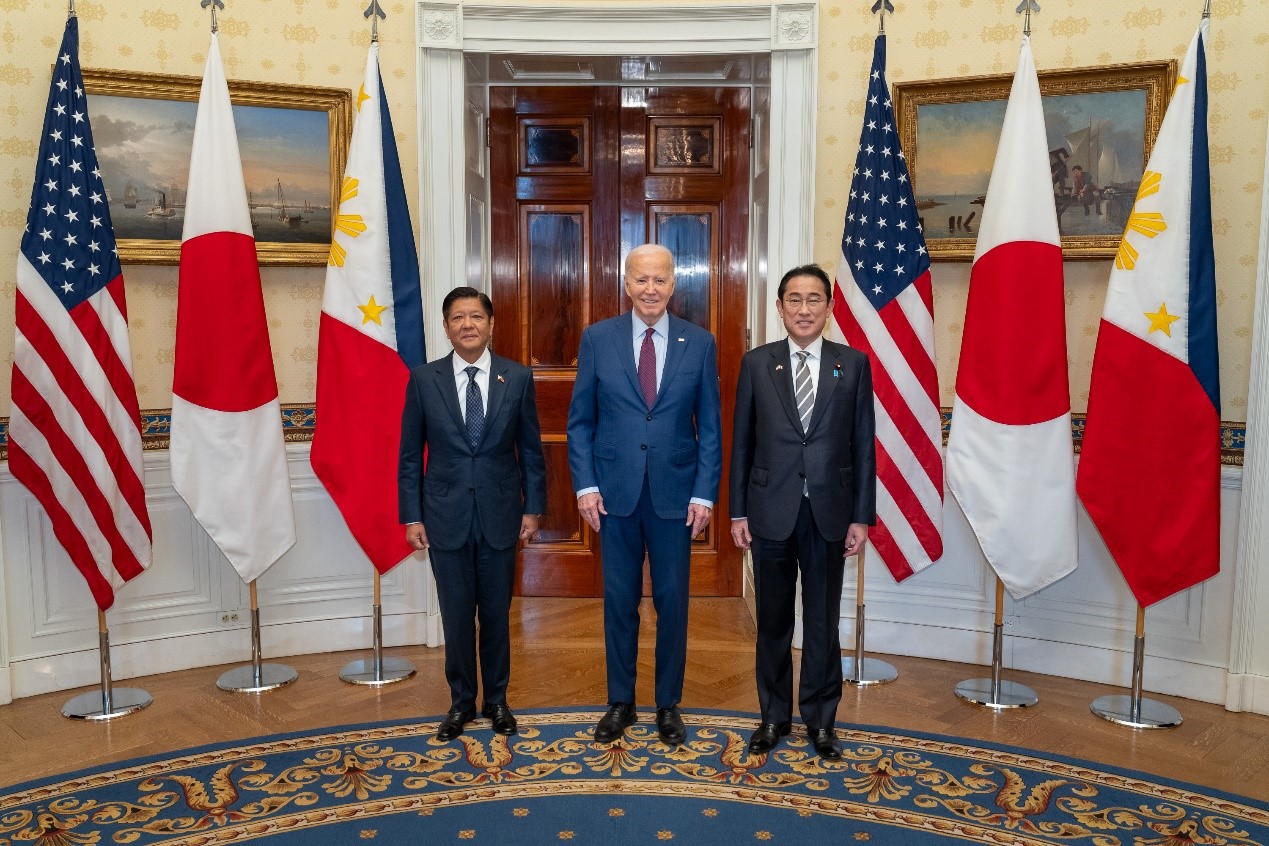

Picture source: Jay Allen, May 19, 2021, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMS_Queen_Elizabeth_and_HMS_Prince_of_Wales_meet_at_sea_for_the_first_time.jpg

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 44

The Return of the Queen? HMS Queen Elizabeth’s Visit to the Indo-Pacific

August 2021

A British carrier strike group led by the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth recently performed a high-profile sea voyage from its naval base in Portsmouth, U.K., all the way to the West Pacific. The maiden operational deployment of the British carrier strike group, dispatched as far as the Indo-Pacific, is noteworthy in terms of its purpose and impact.

U.S. Interests

By no means was Downing Street’s decision to dispatch the carrier strike group to conduct a passage in the sea areas of India and Thailand a sudden one. Suggestions along similar lines had been made as early as during President Trump’s administration, when the then U.S. secretary of defense, Jim Mattis, called on the U.K. to send battleships into the West Pacific to substantiate the concept of freedom of navigation. What this signals is that it is impossible to sustain claims on the issue of freedom of navigation if those are solely acted upon by the U.S. navy. Moreover, any incident taking place in Middle East or the Indian Ocean would tip the military balance held together by the U.S. carrier strike group in the Western Pacific, whose capabilities likely would have to be dispatched to those theaters. Extra weight is therefore needed on the U.S. side. The U.S. needs more allies who are willing to cooperate at sea, particularly those whose navies are equipped with aircraft carriers, such as Britain and France. This perhaps explains why immediately after HMS Queen Elizabeth came into service, as it was in the final stages of sea trials on its long journey, the U.S. did not hesitate to offer close escort. Based upon the shared value of freedom of navigation, the Pentagon is clearly seeking a British role in securing its maritime sphere of influence from South China Sea, the Sea of Japan to the West Pacific.

British Interests

It is natural for London to join the U.S. on key global issues on the ground of the traditionally assumed U.S.-U.K. “special relationship.” The other niche for London is its role as one of the permanent members of the UN Security Council, whose significance looms larger after the U.K. pulled out of the EU; the naval presence bolsters the British status among regional powers. Britain will seize this golden opportunity to end its “era of retreat” by demonstrating its conflict management capabilities when addressing regional tensions.

Britain has hardly pulled out of the strategic picture. For one thing, Britain, India and Australia belong to the Commonwealth, and as we saw, there is a longstanding “special relationship” between the U.S. and the U.K. All these strategic relations ensure that London retains an interest in the complex situation that has emerged in the West Pacific region. Given the maritime practice of joint warfare by the Five Eyes, where the U.S., the U.K. and Australia have laid the cooperative foundations in military and security, there will likely be ample opportunities for joint exercises and maritime training. A closer examination of the joint exercises held by the British carrier strike group shows that the strategic rationale for this mission was to upgrade British capabilities for joint warfare.

Strategic Implications

Although British vessels stationed in Japan may not be taken as the mainstay of maritime operations and are less capable than destroyers, they will nevertheless perform an assisting role by performing tasks including maritime patrols, air defense, and convoy escort. A U.K. presence would relieve U.S. and Japanese warships of some of their enormous workload, and in turn help strengthen the British royal navy’s ability to perform a constructive role in maritime operations in the Indo-Pacific.

While a regular presence by British warships around the Sea of Japan can highlight allied support and closer cooperation, this will increase the risk of direct confrontation with Chinese warships. Looking into the future, we can expect that every time a U.S. warship enters a body of waters in the South China Sea claimed by China, its British ally will run the risk of being dragged into the conflict, and perhaps even clashes.

From a rational point of view, the purpose of the British carrier group visit to the Indo-Pacific may not have been to provoke conflict, or to participate in conflicts and wars, but rather to jointly perform a deterrence task against Chinese military adventurism. If this is indeed the case, then the next question is, if Britain’s purpose is merely to deter, when China insists on taking military action in furtherance of its core interests, should Britain participate in combat operations? The difficulties caused by insufficient long-range maritime combat capabilities on the British side are clear. Although British forces have a rich experience in sending troops to Asia to fight in remote wars, current requirements mean that if the U.K. intends to be part of allied operations, preparedness has to be ensured and mechanisms for joint operations among regional countries is urgently needed.

Future Prospects

Judging from the strategic decision to make the Indo-Pacific the terminal station for the Queen Elizabeth and its strike group, the sea patrols and joint training conducted while there, the stationing of two frigates in Japan and the overall planning over more than half a year, we expect a trend of normalization of British deployments in the West Pacific. In other words, when the Queen Elizabeth and its strike group return to their home port, another carrier strike group will likely head for the Indo-Pacific within six months. Such routine deployments would confirm that British forces are committed to enhancing military cooperation with Indo-Pacific countries and to strengthening their capabilities to take part in joint operations with allies.

It is worth paying special attention to the size and frequency of the joint training exercises between Britain, India, Japan, and Australia. The numbers involved will reflect the general attitude of countries in the Indo-Pacific toward China’s maritime threats as well as the degree of instability as the strategic situation develops.

Some scholars are still adamant that Britain should focus its strategic attention on the NATO and security issues in the Atlantic region, and have called for strengthening British influence across the Atlantic. This argument makes sense on the grounds that, after Brexit, the EU currently lacks firm support from a main power and it is troubled by Russian coercive attempts over Ukraine. Viewed in this light from the European angle, the security burdens both on the EU and Britain are much heavier, which may justify calls for British staying power within the European theatre Given this context, the U.K.’s timely decision to dispatch an aircraft carrier strike group into the Indo-Pacific Region is all the more telling. Among other things, it illustrates the self-defeating effects of China’s wolf warrior diplomacy. China’s activities in the West Pacific loom larger in the West's strategic calculations and have aroused the attention of the U.S. and its allies who, more than ever, understand the need to take preventive measures. As a country that has long been part of the U.S.-led alliance, Britain would find it hard to disassociate itself from such responsibilities.

(Dr. Shen is Research Fellow, Institute for National Defense and Security Research)