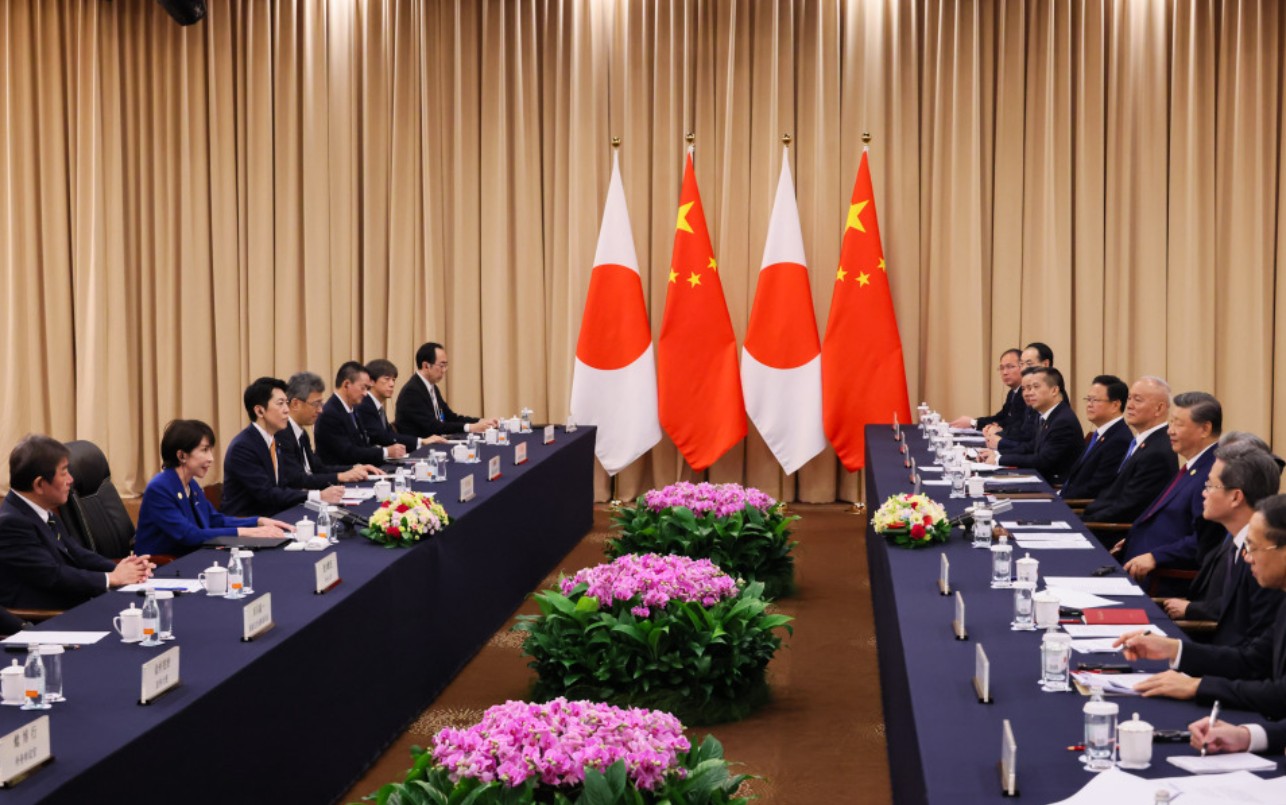

The whole process of adopting an Indo-Pacific strategy reflects an undeniable willingness to place constraints on Chinese behavior. And in substance, European cooperation with “alternatives to China” will deepen as a result, especially with Australia, India and Japan, including in the area of security cooperation. Picture source: Council of the European Union, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/eucouncil/photos/3953785988004360/.

Prospects & Perspectives 2021 No. 25

The EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy

Mathieu Duchâtel

Director of the Asia Program at Institute Montaigne in Paris

By the end of 2021, the European Union should have an Indo-Pacific Strategy. In late April, the Council of the European Union reached a consensus on the political priorities to be pursued in the upcoming strategic document which the Commission and the High Representative of the Union have been tasked to formalize by September.

The Indo-Pacific is first and foremost a “mental map” guiding foreign and security policies. The EU has been slow to embrace the Indo-Pacific mental map. The current process is the result of the leadership of France, Germany and the Netherlands within the EU institutions. Like any EU foreign policy document, it will reflect a balancing act between the interests of 27 Member States, and the coordinating and leadership skills of the Commission. What is going to be the impact of this process on EU-China relations? After all, the Indo-Pacific would not exist if there was no need to balance the rise of China. This, indeed, has been a starting point of the European decision-making process. But it is not the only one. Many European actors involved in the Indo-Pacific discussion simply see the embrace of the concept as a convenient label to push their foreign policy agendas towards the states of the Indo-Pacific region and will resist any language that risks antagonizing China. Many simply see the Indo-Pacific as an unavoidable geopolitical reality that creates engagement and cooperation opportunities.

The EU’s adoption of an Indo-Pacific strategy risks resulting in a diluted document listing and rephrasing many existing international priorities on the EU’s agenda. But even if this is the case, there will still be some tangible elements from the angle of balancing China’s rising power.

The Balance of Power Origins of the Indo-Pacific

Japan and Australia, the early advocates—including in Washington—of the Indo-Pacific, promoted the notion as a defensive vision in response to China’s deepening global footprint in that immense maritime space. Once endorsed by the Trump administration, the United States unrolled its own version of the concept as a precise list of strategic objectives and tactical options contained in strategic framework recently declassified by the NSC, “U.S Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific”.

The NSC memo does not mention Europe. In the Trump administration’ vision, to maintain U.S. strategic primacy and economic leadership in the Indo-Pacific region, Europe was clearly a dead angle. And indeed, Europe’s recent embrace of an Indo-Pacific mental map is not an outcome of transatlantic alliance dynamics. Rather, it represents Europe’s own assessment that the Indo-Pacific space has become a geopolitical center of gravity which can no longer be ignored.

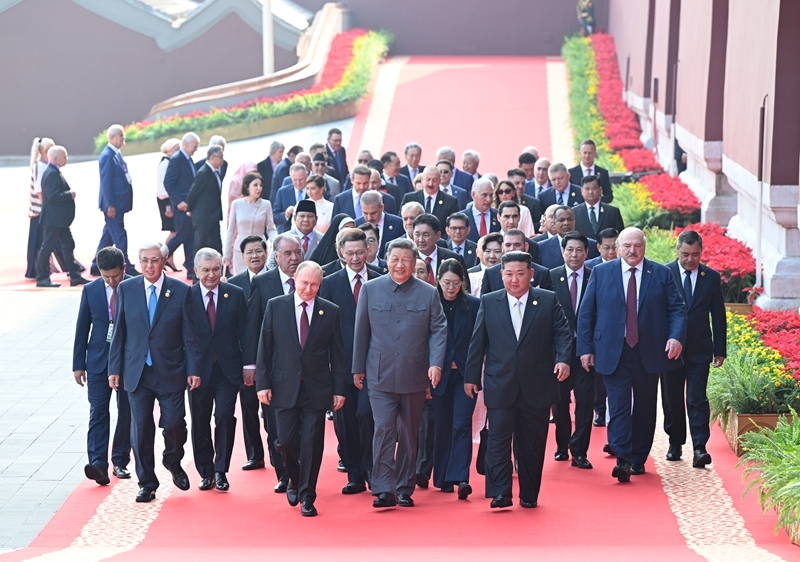

But the EU’s starting point is different from the early proponents of the Indo-Pacific. There have always been nuances and differences in how its four largest stakeholders—the “Quad” members, Australia, India, Japan and the United States—understood the Indo-Pacific. But their cooperation rests on a clear common rationale: China’s strategic expansion, especially through its investment in naval power projection, and the critical infrastructure projects it conducts in third countries under the Belt and Road Initiative.

The Quad’s version of the Indo-Pacific is premised on a realist balance-of-power world view. It accepts the competition for influence in third countries as a starting point. As terminology has also shifted in Europe, it is striking that EU officials promote the Indo-Pacific as part of the idea that the US-China rivalry can be neutralized by multilateralism, diluting the concept away from its initial focus on the changing balance of power with China.

The Third Way? Whither China Containment

European diplomats argue that the Indo-Pacific should be an inclusive notion without a China target. Rather than China’s power game, they see U.S.-Chinese competition as the central problem. France, Germany and the Netherlands all emphasize a European goal to prevent the Indo-Pacific from being a space defined only by the Sino-American rivalry. As a senior EU diplomat made clear, “We are charting a third way between Washington and Beijing.”

For France, this language represents an adjustment. The French Ministry of Armed Forces was one of the earliest advocates of adoption an Indo-Pacific outlook. This was linked to the perceived challenge against freedom of navigation under UNCLOS. France has 1.5 million nationals and an EEZ of nine million square kilometers in the Indo-Pacific—an EEZ contested in some areas of the Mozambique Canal and around New Caledonia. 8,000 military staff are deployed to protect them, and six new patrol ships are to be commissioned for deployment in the Indian and Pacific Oceans between 2022 and 2025. This national sovereignty prism colors how France sees China’s challenge to the maritime legal order in the South China Sea, where Chinese claims are not articulated or pursued in a way compatible with UNCLOS.

But this initial international law/military balance/hard security focus is currently being watered down. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs favors a larger framework that encompasses all diplomatic and economic cooperation dimensions. This shift to a wider agenda has facilitated convergence with Germany and the Netherlands. Germany approaches the Indo-Pacific as an “internationally active trading nation” with an interest to avoid “a new bipolarity with fresh dividing lines across the Indo-Pacific”, and focuses on the promotion of multilateralism and on the importance of strengthening ASEAN. The Netherlands’ paper focuses on cooperation on six areas: promotion of democracy and human rights, security and stability, sustainable trade and investment, effective multilateralism and the rule of law, sustainable connectivity including digital, working together on global challenges, including climate and Sustainable Development Goals.

Engagement in Substance: Infrastructure Development and Security

An inclusive and non-confrontational posture will facilitate endorsement from other EU Member States which tend to think of the region in terms of economic opportunities, rather than one of strategic balance. The green transformation and the digital revolution are a domestic priority for European companies, but also a chance to win infrastructure development projects—or shares of such projects, including some carried out by Chinese State-Owned Enterprises. Digital connectivity, 5G and green mobilities also create opportunities to link up to infrastructure projects led by Japan, India and Australia, and to standard setting initiatives like the United States’ Blue Dot network.

Other commercial opportunities will have an impact on the balance of power. China’s naval expansion means that Indo-Pacific states need improved maritime domain awareness. Illegal fishing in their EEZ is also a serious issue, and maritime awareness is essential to managing natural disasters. France and the Netherlands are already involved in capacity-building through public and private solutions.

The turn to a pro-business agenda in European thinking regarding the Indo-Pacific somehow obscures the maritime security origin of the concept. In Europe, the Indo-Pacific discussion started as an issue of defense of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea. Regular transits by the French and the British navies still signal support for freedom of navigation under UNCLOS in a maritime space where no clear delimitation of China’s claimed territorial seas and EEZ is known, but where China has a stated policy goal to restrict access by navies from outside the region. This is happening despite the risk that the Chinese Navy could provoke an incident to undermine the resolve of nations present in the South China Sea (besides the United States, Australia, Japan and Canada have all dispatched ships, and the German Navy will transit through the South China Sea for the first time in 2021).

Recalibrating Europe’s Positioning Away from Sino-Centrism

It has been a constant in French and German foreign policy under the Macron-Merkel duo to emphasize the goal that the international order should not be defined by the U.S.-China rivalry. The current EU Indo-Pacific language reflects that thinking. This means that the EU will seek to avoid alignment with the United States on China policy, and will be extremely reluctant to admit that its Indo-Pacific strategy is about balancing China’s rise. The whole process of adopting an Indo-Pacific strategy reflects an undeniable willingness to place constraints on Chinese behavior. And in substance, European cooperation with “alternatives to China” will deepen as a result, especially with Australia, India and Japan, including in the area of security cooperation. What could tilt the balance away from the EU’s extreme caution is the upcoming change of leadership in Germany after the September federal elections.