The Strategic Orientation of the Ishiba Cabinet and its Implications for Taiwan-Japan Relations

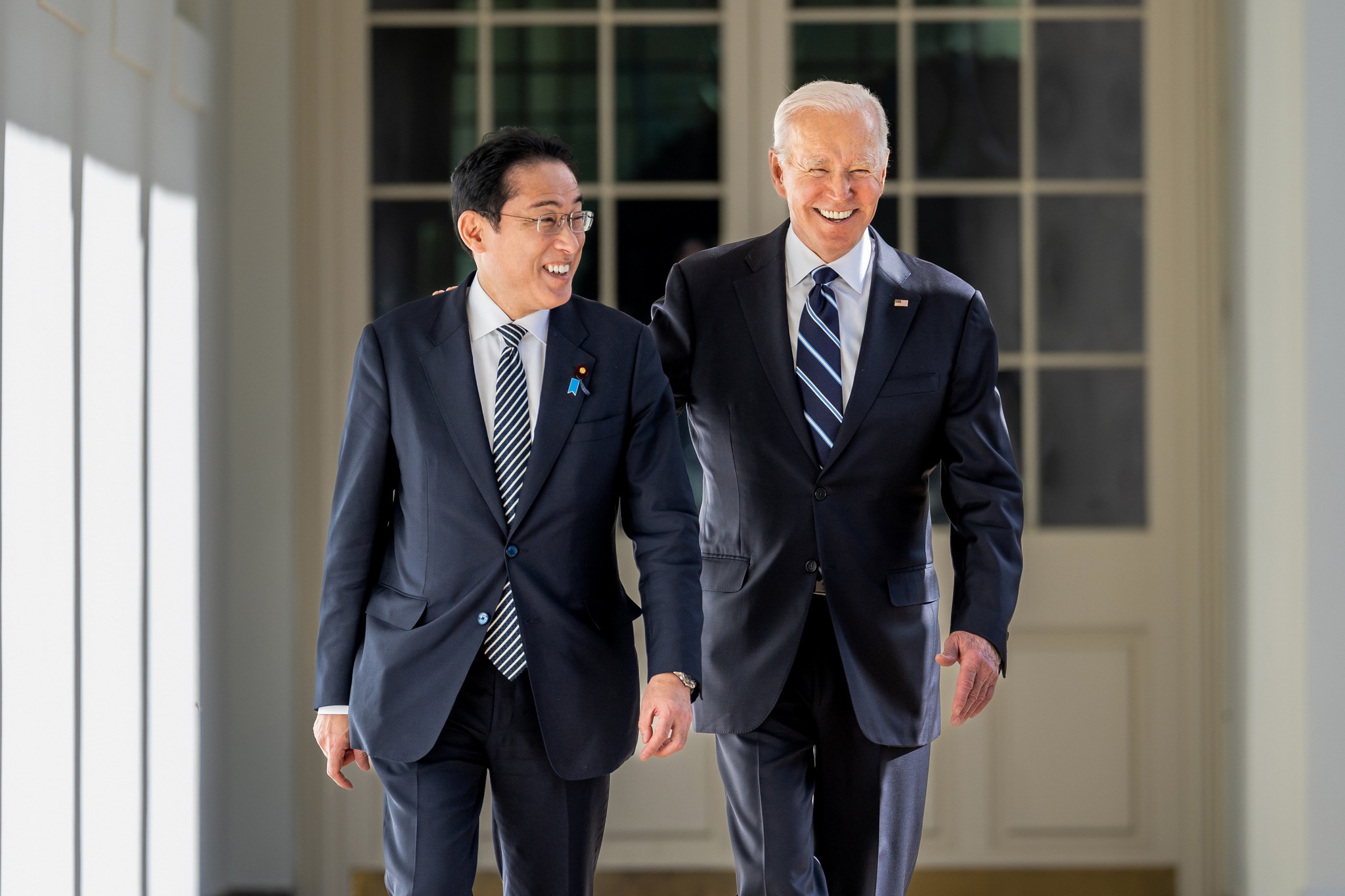

As internal and external dynamics feed off each other, Ishiba’s leadership presents an opportunity for Japan to redefine its international role and strategically adapt to new realities. While his bold proposals resonate with national security concerns, Ishiba is unlikely to push aggressively on the international stage. Picture source: PM Office of Japan, October 4, 2024, https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/102_ishiba/statement/2024/1004shoshinhyomei.html.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 56

The Strategic Orientation of the Ishiba Cabinet and its Implications for Taiwan-Japan Relations

By Yujen Kuo

Shigeru Ishiba took over as Japan’s new prime minister by a narrow margin at the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) leadership race on September 27. The race for the new head of the LDP was fierce, pitting Ishiba against the conservative rival Sanae Takaichi and the rising star Shinjiro Koizumi. Takaichi led the first round without a majority and was considered to have also won the second round. Surprisingly, the 67-year-old Ishiba secured 215 votes and narrowly defeated Takaichi, who obtained 194 votes. This was largely thanks to support from the former prime ministers Fumio Kishida and Yoshihide Suga. Takaichi consistently appealed to the conservative hard-right, a stance that worried many LDP diet members, who apprehended that a shift to the right could undermine the LDP in the coming general election. This, thus, also played in Ishiba’s favor in the second round.

A minority at LDP and variety of domestic problems

Unlike his predecessors, Ishiba does not have a solid power base in the party and will face major challenges from factional politics. He will have to play a game he is not good at to unite the various LDP factions. To consolidate party cohesion, Ishiba appointed Suga as vice president and Taro Aso as supreme advisor of the LDP. He also skillfully included several Aso faction members in key Cabinet positions to smooth over potential friction in order to tackle a range of domestic and geopolitical challenges.

Economic problems will occupy center stage of the new Ishiba Cabinet, since both Abeconomics and Kishida’s economic policy failed to deliver results. Wages have remained stagnant for over 30 years, living costs are rising, and the welfare system is creaking under pressure. Japan also has the largest national debt in the world, making it extremely difficult to deal with these issues. In addition, the Japanese people are tired of the endemic corruption within the LDP, which was the main trigger for Kishida’s decision to step down. To rapidly deliver on the economy and regain public trust will be top priorities and the most challenging tasks for Ishiba.

Solid alignment with the U.S. despite bold proposals

On the international front, Ishiba’s track record suggests a willingness to take a more active stance on key issues while fostering greater multilateral cooperation to reassure Japan’s international partners about the continuity of Japan’s leadership. The Free and Open Indo-Pacific Initiative will continue to serve as the guiding framework for Ishiba’s foreign strategy, though with several minor adjustments in how Tokyo manages Japan’s relationships with the U.S., China, and Taiwan. He will not deviate too much from his predecessors and will continue to maintain the close U.S.-Japan alliance, and to implement the 2022 National Security Strategy, which requires increasing defense spending to 2% of GDP by 2027

Ishiba has emphasized the importance of the U.S.-Japan alliance while advocating for an equal partnership like that between the U.S.-U.K. He has called for negotiations on the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) for the joint management of U.S. bases in Japan. In addition, he has raised the possibility of stationing Japan’s Ground and Air Self-Defense Forces (SDF) on Guam and other U.S. territories to enhance the SDF’s full-scale training and elevate mutual trust and interoperability.

Ishiba’s proposal could reshape the alliance’s dynamics, promoting shared responsibilities and deeper military integration. However, revising SOFA would affect the U.S.’ global alliance policy and require U.S. Congress approval, which may require delicate negotiations to align with U.S. policies and domestic sensitivities regardless of the next U.S. administration. It could prove even more challenging if Donald Trump returns to the White House with the insistence that Japan shoulder more responsibility and cover more of the expenses for U.S. forces in Japan.

China remains the most daunting challenge

A Japanese frigate sailed through the Taiwan Strait alongside Australian and New Zealand navy vessels in late September, highlighting the complex geopolitical relationship with China. Ishiba’s tough stance is evident, aimed at countering China’s ambitions to change the status quo through gray zone tactics and coercive measures. In response to China’s intrusion into Japan’s airspace, he has advocated for Japan to amend laws to allow the SDF to conduct “hazardous firing” to deter Chinese aircraft. Despite this tough approach, Ishiba also recognizes the necessity of balancing deterrence with diplomacy, and will promote a mutually beneficial strategic relationship with Beijing.

In addition, Ishiba believes that an “Asian NATO” would be the ideal mechanism under the current regional landscape of a declining U.S. and a rising provocative China by organically combining the U.S.-Japan, U.S.-Korea and the Australia-New Zealand-U.S. treaty (ANZUS) frameworks. However, large disparities in strategic interests and conflicting security priorities among Asian countries, as well as a lack of a specific adversary, make the materialization of such an ambitious proposal unlikely in the foreseeable future — and this does not even include the complicated historical baggage into account.

Following the same logic, Ishiba believes the U.S.’ current nuclear umbrella is no longer sustainable in the face of a tight Russo-North Korea nuclear alliance on top of the daunting nuclear challenge posed by China. He has suggested revising Japan’s Three Non-Nuclear Principles and to explore nuclear sharing with U.S. The feasibility and practicality of such an idea — about which there are no specific details so far — is speculative and highly controversial domestically, and could furthermore exacerbate regional tensions.

As internal and external dynamics feed off each other, Ishiba’s leadership presents an opportunity for Japan to redefine its international role and strategically adapt to new realities. While his bold proposals resonate with national security concerns, Ishiba is unlikely to push aggressively on the international stage. A more feasible alternative, one that was shared by his predecessors, is to build issue-oriented mini-lateral coalitions such as the QUAD, AUKUS and Squad on maritime or cyber security rather than a rigid structure such as a formal military bloc in the Indo-Pacific.

Taiwan’s active role in U.S.-Japan Alliance during the Ishiba era

As a defense expert, Ishiba’s victory also suggests that security-oriented adjustments in Japan’s relations with Taiwan should be expected. In August, Ishiba visited Taiwan and met President Lai Ching-te, during which he stressed that “today’s Ukraine might become tomorrow’s East Asia” and “We have to rack our brains” to prevent that scenario from happening. Ishiba especially emphasized the importance of developing “integrated deterrence” with Taiwan, though he does not agree with the late former prime minister Shinzo Abe that “a Taiwan contingency is a Japan contingency.”

Ishiba’s opposition to Abe’s famous saying stems from military considerations hypothesizing Japan’s dilemma in the event of a Taiwan contingency, in which Japan would be forced to side with the U.S. based on Article 3 of the bilateral security treaty and would place Tokyo in a difficult position vis-à-vis China, with Japan potentially becoming a target of Chinese retaliation. Despite these complexities, Ishiba has touted the concept of “integrated deterrence” with Taiwan that remains rooted in the U.S.-Japan alliance.

In conclusion, while Taiwan may face challenges in achieving significant diplomatic breakthroughs during Ishiba’s leadership, given his focus on integrated deterrence, there is a path forward. It can be hoped that the August meeting between Ishiba and Lai has laid a solid foundation for Taipei-Tokyo relations in the coming years. Taiwan should inn turn more actively enhance its visibility and role within the broader U.S.-Japan strategic framework by strengthening its security integration with the U.S.

(Dr. Kuo is Professor, Institute of China and Asia-Pacific Studies, National Sun Yat-sen University.)