Although Ukraine is making good progress in its accession bid to join the EU, the way ahead is still unclear. Ukraine’s bid to join the EU will not only determine Ukraine’s own destiny, but will also affect the EU itself, as well as the future of global security and common values. Picture source: President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, January 19, 2023, https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/masshtab-nashoyi-spivpraci-ye-novoyu-istoriyeyu-i-dlya-ukray-80477.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 2

Ukraine’s Accession to the EU: There’s Still a Long Way to Go

By Yun-chen Lai

Ukraine’s diplomatic choices have been a source of heated debate domestically. After Russia’s invasion of the country in 2022, the crisis became an imperative matter for European and global security. Located between the EU and Russia, Ukraine became a so-called “buffer zone” after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. After Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution in 2013-2014, its pro-EU leaders quickly strengthened Ukraine’s relations with the EU. In 2014, Ukraine and the EU signed the Association Agreement, which serves as the basis for implementation of the accession process. In February 2022, a week after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine submitted a letter of application for EU membership, officially starting the process of joining the EU. In June 2023, the EU surprisingly quickly granted candidate status to Ukraine and announced in December that it agreed to start accession negotiations with Ukraine.

Accession process for joining the EU

Any European country that meets the standards of the EU’s common values, including respect for human dignity and human rights, freedom, democracy, equality and rule of law, can apply to join the EU. However, the accession process is quite complicated and can take years — and there is no guarantee that an applicant will ultimately be allowed to join. In practice, before the official accession process is launched, the EU uses association agreements to help countries that wish to join the EU stabilize their politics and encourage their transition to market economies so that they can meet EU standards for joining. After the association agreement is constructed and implemented, the applicant can submit the application to officially start the accession process. The process involves three main steps: candidacy, accession negotiation and treaty ratification. For the 21 current members that underwent the accession process, it takes nine years on average from the submission of an application to official accession (the shortest time was three years for Finland and longest was 13.5 years for Malta and Cyprus). If the time spent from application to the start of the accession negotiation is calculated, it takes 3.5 years on average. Thus, the 22 months from February 2022 to December 2023 for Ukraine to begin the accession negotiations after its application is relatively quick.

Ukraine’s efforts and the EU’s response

While approving Ukraine’s candidate status in June 2023, the EU set seven conditions for Ukraine, including reforms of its constitutional court, judicial governance, anti-corruption, anti-money laundering, de-oligarchization, media legislation and protection of national minorities. The EU emphasized that only when those requirements have being reached could the accession negotiations begin. The Ukrainian government pledged to finish the reforms as soon as possible. In November 2023, six months after receiving candidate status, Ukraine reported to the EU that four of the seven requirements had been implemented and that it was making good progress on the remaining three. Consequently, the questions of whether to start the accession negotiations with Ukraine was tabled during the EU Summit of the European Council in December 2023.

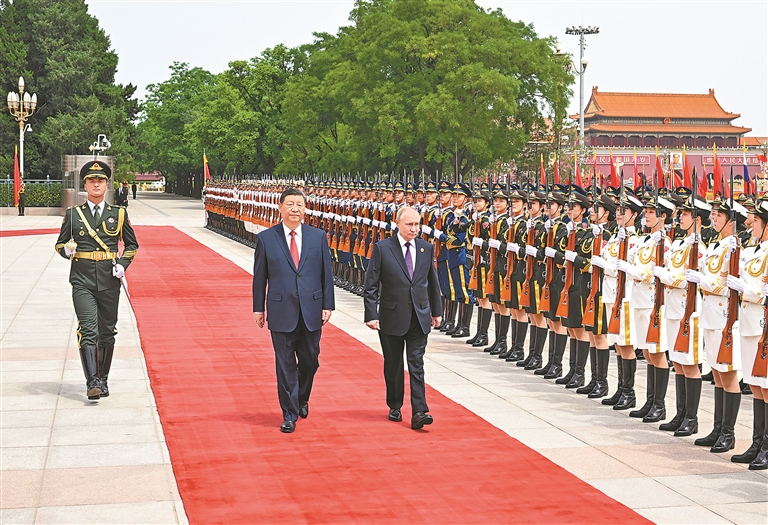

Before the Summit, the situation was not so optimistic. The start of accession negotiations requires an unanimous decision by the European Council. However, the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orban, who is close to Russian President Vladimir Putin, strongly opposes EU membership for Ukraine. Thus, it was widely expected that Orban would cast a veto in the Summit to obstruct Ukraine’s accession. However, surprisingly, Orban walked out of the room when EU leaders voted on the start of the accession process, meaning that he was abstaining. As a result, the accession negotiations between the EU and Ukraine have begun and Ukraine can now start the second phase of the accession process.

The way ahead for Ukraine’s membership in the EU

Even though Ukraine has earned its reward for its work on reforms and received the EU’s permission to start the accession negotiations, there is still a long way to go. According to statistics, the second phase of the accession negotiations is by far the longest procedure. On average, it requires about four years from the start of accession negotiations to officially accession. Besides, Ukraine will need years to strengthen its judiciary and independent media, fighting corruption, reforming its security establishment and building sound public institutions to meet EU standards. What complicates matters is the fact that EU member states hold various opinions when it comes to Ukraine’s accession, making the future of Ukraine’s accession replete with uncertainty.

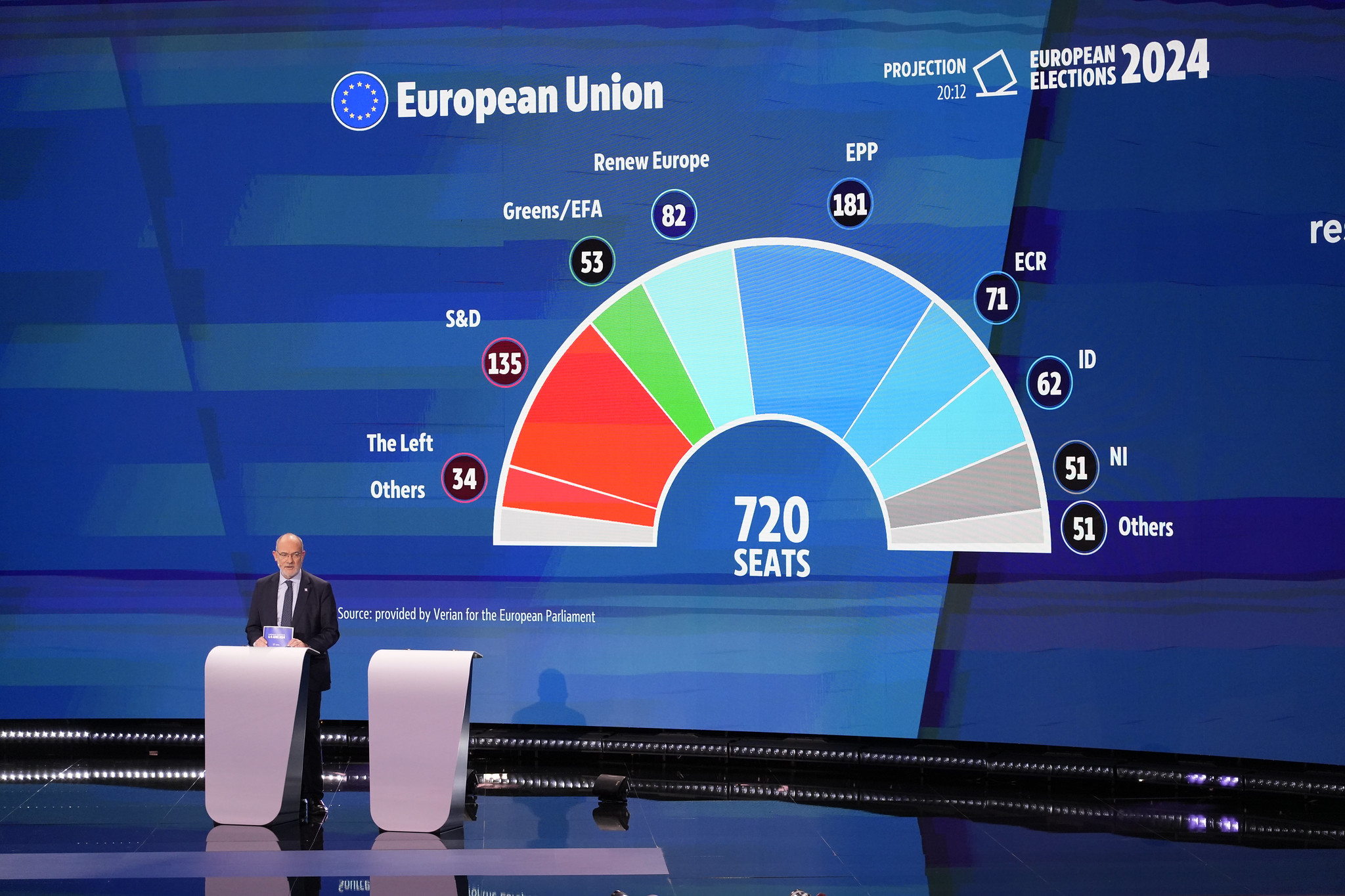

Divisions among EU member states

Although there is basic consensus among EU member states to support Ukraine in its resistance to the Russian invasion, eastern and western members differ in their concrete approaches to confronting Russia. Western members, mainly represented by France and Germany, have attempted to maintain an open dialogue with Russia, as they highly depend on Russia’s energy supply. However, the attempt has failed due to disagreement by Baltic members who seek a significant Russian military drawdown, as they are highly sensitive to the military threat posed by Russia. This highlights the contradictions among member states on defense matters.

While the center of gravity and priorities of the European Union shifted toward its east after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, eastern EU members have not been coherent in their policies. Poland and Hungary have held totally opposite positions to the Union’s relationship with Russia. While the former has played a leading role in confronting Russia, the latter remains opposing to sanctions against the Russian government. This contradiction has fractured the Visegrad Group — composed of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia — which plays a leading role among central and eastern European countries.

Further, even for eastern Europe members who firmly support Ukraine in its resistance to Russia’s military invasion, such as Poland and Slovakia, there are still contradictions with Ukraine when it comes to the agricultural sector. To protect their farmers from an influx of cheap products from Ukraine, Poland and Slovakia announced they would continue to impose a ban on Ukrainian grains after the restrictive measures by the European Commission on Ukrainian grains ended in September 2023. Those countries have also stated their fears that the integration of Ukraine into the European single market could cause problems. Those pronouncements shocked the European Commission and put member countries on a collision course with the rest of the EU.

In short, there are many contradictions among current EU members when it comes to the Ukrainian issue. Those contradictions regarding defense as well as agriculture have complicated Ukraine’s path to EU accession.

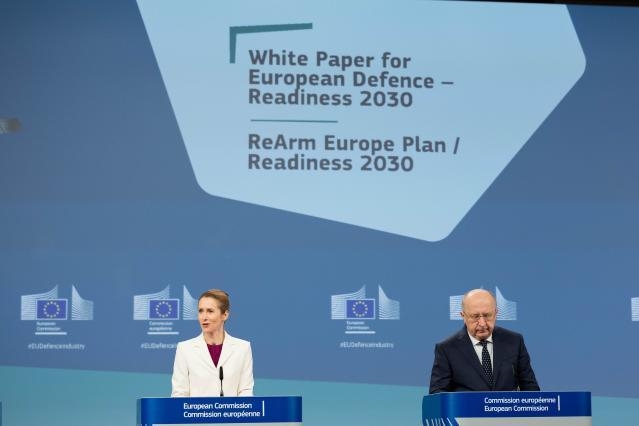

The need for EU institutional reform

Divisions among member states regarding Ukraine’s accession to the EU underscore the need for institutional reform at the EU. Currently, when it comes to sensitive sovereignty issues, such as the accession of a new member, Common Foreign and Security Policy and common defense, social security or social protection, an unanimous decision is required. This undermines efficient decision-making. In the case of Ukraine, even if there is basic consensus on the need to resist Russia’s invasion among most EU member states, one single country, Hungary, can obstruct the majority opinion of the other 26 countries. This reveals the problem of the EU as an institution. Thus, several member states, such as France and Germany, hope to reform the EU mechanisms by applying qualified majority voting (QMV) to more issues to make decision-making more efficient. However, even on this project there is still major disagreement among member states.

Conclusion

Although Ukraine is making good progress in its accession bid to join the EU, the way ahead is still unclear. Much of it depends on whether Hungary will change how it position itself between Ukraine and Russia, as well as on whether members will accept the impact of Ukrainian agricultural imports. Further, the EU as an institution and the reform process within that institution will play a crucial role in determining Ukraine’s accession to the Union.

Historically, crises have created opportunities for the EU. Reforms made by the EU in times of crisis have often made it stronger. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has highlighted many of the EU’s weaknesses and contradictions, particularly on matters of defense. Ukraine’s accession bid further highlights the divisions among member states on matters of agricultural products, which have long plagued the EU. However, if the problems that Ukraine’s bid have brought to the fore can trigger EU institutional reforms, the crisis can one again turn to an opportunity to make the EU stronger. Ukraine’s bid to join the EU will not only determine Ukraine’s own destiny, but will also affect the EU itself, as well as the future of global security and common values.

* This is part of the results of a NSTC research project; project number: 112-2410-H-259 -020

(Dr. Lai is Professor, Department of Public Administration, National Dong Hwa University.)

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily flect the policy or the position of the Prospect Foundation.