Australia’s Defence Strategic Review: A Realistic Assessment without Sufficient Execution

Overall, Australia’s Defence Strategic Review makes the right strategic assessments about the increasing risk of military conflict, puts forward the right deterrent by denial strategy, makes the right calls in terms of force re-structure, but then fails to fund the development of critical capabilities in the urgent timeframe it identifies.

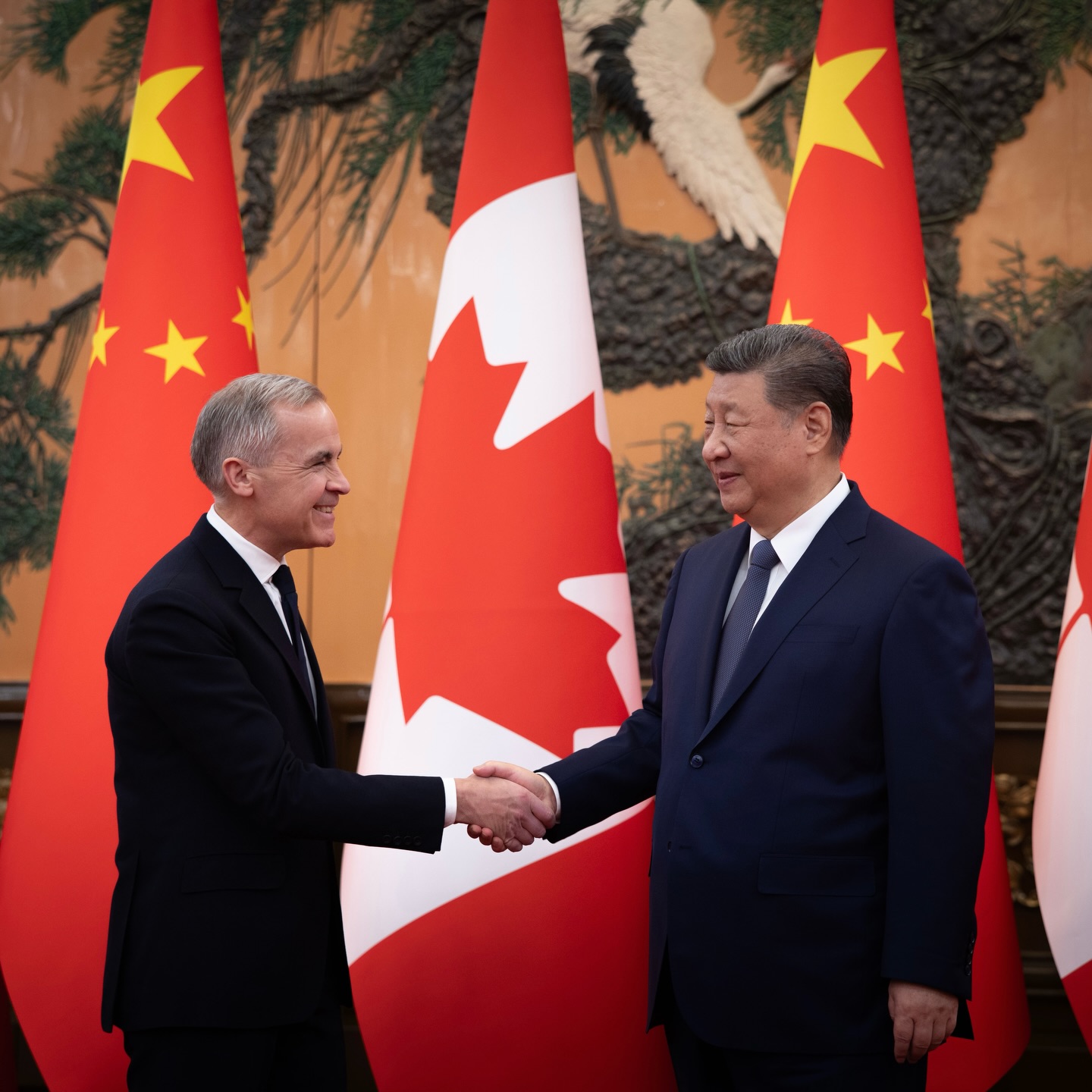

Picture source: Defence Australia, May 17, 2023, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=646411380859735&set=pcb.646411544193052&locale=zh_TW.

Australia’s Defence Strategic Review:

A Realistic Assessment without Sufficient Execution

Prospects & Perspectives No. 29 May 30, 2023

By Lavina Lee

Australia’s Defence Strategic Review: A Realistic Assessment Without Sufficient Execution

In August 2020, in the first 100 days of taking office, the new Australian Labor government announced that it was commissioning an independent Defence Strategic Review (DSR) to “assess whether Australia had the necessary defence capability, posture and preparedness to best defend Australia and its interests in the strategic environment we now face.” The public version of that review was released in April 2023, with the government supporting its key strategic assessments and recommendations. The Review represents the most ambitious review of its type undertaken since World War II, in response to strategic circumstances that Australia has not encountered since then: the emergence of a great power in East Asia with interests inimical to its own.

The DSR gets some things right. It correctly assesses the heightened risk of regional conflict, identifies the need for urgent defence preparations and puts forward a deterrent strategy and prioritization of defence posture and capabilities befitting Australia’s resources and geography. However, while the government has agreed with almost all of the Review’s recommendations, it has failed to follow through with an increase in defence funding over the next three-four years, contradicting its basic message that urgent changes to defence capability, posture and preparedness are now needed.

Key takeaways

There are four key takeaways from the Review. First, the DSR starts with the stark assessment that the strategic circumstances and risks Australia now faces is “radically different” to those of the previous 80 years. This is the result of the decline in U.S. relative power, the emergence of intense China-U.S. competition, and an increased risk that this competition may result in military conflict. It is unusually direct in identifying China as the primary source of threat to Australian interests, criticizing its assertion of sovereignty over the South China Sea, strategic competition in Australia’s “near neighborhood” (i.e. the Pacific and Southeast Asia), and lack of “transparency” and “reassurance” about the strategic intent behind its ambitious and unprecedented military build-up.

Second, the Review confirms the 2020 Defence Strategic Update’s (DSU) abandonment of a 10-year strategic warning time — “the time a country estimates an adversary would need to launch a major attack against it” — as the basis of defence planning. It posits that the concept of “warning time” is no longer valid in the contemporary strategic era, given the ability of more countries (read China) to project combat power over greater ranges in all five domains (for example, via precision strike weapons and cyber attacks). Australia’s geography therefore can no longer be relied upon to provide strategic depth. As a consequence, the end of warning time for a major attack now “necessitates an urgent call to action, including higher levels of military preparedness and accelerated capability development.” In other words, Australia and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) now need to be prepared for the possibility becoming involved in conflict in our region, including an attack on Australian territory at any time. The Review replaces the 10-year warning time for defence planning with three time periods: the three-year period from 2023-2025 for matters that need to be addressed urgently; the five-year period from 2026-2030; and the period 2031 and beyond.

Third, to respond to this heightened risk of involvement in major conflict, the Report overwhelmingly recommends that Australia follow a defensive strategy of deterrence by denial. In pursuing this strategy, the ADF’s primary area of military interest is defined as Australia’s immediate region i.e. “the north-eastern Indian Ocean through maritime Southeast Asia into the Pacific” including its northern approaches. Such a strategy of denial is realistic and appropriate, given the vast imbalance of size and capability between Australia and China. It involves the development of anti-access/area denial capabilities (A2/AD) to deny an adversary’s ability to militarily operate against or coerce Australia without its forces being held at risk at a greater distance, particularly via long-range strike, undersea warfare capabilities and surface-to-air missiles.

Fourth, in terms of force structure the Review abandons the “balanced force” concept that has guided the ADF’s force structure for decades, whereby Australian forces needed to be ready to respond to low level threats to Australian territory, to contribute to regional operations and to provide global support to the United States as its alliance partner. This is now replaced by the concept of an “integrated force” (integrated across the five domains) and “focused force” optimized to deliver a deterrence by denial strategy against a highly capable great-power adversary.

Significant changes to force structure for each service have been recommended to give effect to deterrence by denial. The navy will need to develop enhanced lethality via the acquisition of conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines (AUKUS Pillar 1) and a larger number of tier 1 and tier 2 surface combatants to contribute sea denial, air defence, long-range strike, and anti-submarine warfare capabilities. The army is to be transformed to conduct littoral maneuver operations by sea, land and air from Australia, with enhanced long-range fire capability (land-based maritime strike). In turn, the air force must be configured to provide air support for joint operations in Australia’s north by conducting surveillance, air defence, strike (maritime and land) and air transport. As part of the review, the government has allocated A$1.6 billion to acquire more long-range strike systems, including accelerated delivery of HIMARS launchers and Precision Strike Missiles, while the U.S. has previously agreed to sell Australia up to 220 Tomahawk land-attack missiles (TLAM) to equip the RAN’s three Hobart class destroyers, and LRASMs for Australia’s two fighter jets (the FA-18F Super Hornet, and the F-3A lighting II strike fighters). A further A$2.5 billion is set aside to develop a domestic missile production capability, or the guided weapons and explosive ordnance enterprise (GWEO). Australia is essentially upgrading its military capabilities to independently (of the United States) defend the air and sea approaches to Australia, project integrated maritime and air power in our region, and provide meaningful augmentation to the U.S. Navy to close shipping routes.

Finally, like the debates over force structure and capability in Taiwan, the review calls for a focus on asymmetric advantage in relation to pursuing a strategy of denial, that is, “the application of dissimilar capabilities, tactics or strategies to circumvent an opponent’s strengths, causing them to suffer disproportional cost in time, space or material.” The government has accepted the reviews recommendation that the development of critical technologies as part of AUKUS Pillar II (autonomous underwater vehicles, quantum technologies, AI-enabled systems, hypersonic and counter-hypersonic capabilities, electronic warfare) should be urgently prioritized, with a senior official or officer to be given sole responsibility for expediting capability outcomes.

Critiques of the Review: an absence of urgency despite a deteriorating environment

While these aspects of the Review are difficult to fault, there are others that have come under significant criticism. First are the Review’s recommendations that further reviews of key capabilities be undertaken. This includes a further 12-month review of options for the increase of guided weapons and explosive ordnance stocks (i.e. long-range strike), including the development of a domestic production capability (GWEO enterprise). This means that there has been no meaningful enhancement of Australia’s long-range strike capabilities since the need to do so was first identified in the DSU of 2020. It is unclear why this review could not have covered this task rather than “kicking the can down the road” for another year. A further six-month review of the navy’s surface fleet has also been criticized for the same reason, and especially so given the Review’s dire assessment of the nation’s strategic circumstances. It suggests that there will be changes to Australia’s existing — and long delayed — Hunter-class frigate program. Finally, there is complete absence of additional funding for defence over the next four years — again despite the Review’s dire strategic assessment. The recommendations adopted by the government will cost A$19 billion over four years drawn from the existing defence budget, with A$7.8 billion coming from cutting, delaying or cancelling programs such as armored troop carriers and base upgrades.

Overall, the review makes the right strategic assessments about the increasing risk of military conflict, puts forward the right deterrent by denial strategy, makes the right calls in terms of force re-structure, but then fails to fund the development of critical capabilities in the urgent timeframe it identifies. The review makes no mention of the possibility of conflict in the Taiwan Strait and provides no additional defence spending over the next four years, the period in which sending a collective deterrent signal to China is the most needed. With the demands of the Ukraine war placing pressure on U.S. missile manufacturers it is unlikely that Australia will enhance its long-range strike capabilities in this timeframe either. Added to this is the fact that Australia’s first Virginia-class nuclear powered submarines and its Hunter class frigates are not due to be delivered until the early half of the 2030s. The asymmetric capabilities to be developed under AUKUS Pillar II could be delivered in a closer time-frame but this is still a work in progress with only around A$151 million specifically committed to Pillar II initiatives over the next four years. All in all, there is a considerable credibility gap in the Review which can only be fixed with a true change in mindset and a significant increase in defence spending beyond business as usual. The government has acknowledged that defence spending will need to significantly increase beyond 2 percent of GDP beyond the next four years and into the medium term. We can only hope that events do not move faster than this time-frame.

(Dr. Lavina Lee is Senior Lecturer, Department of Security Studies and Criminology, Macquarie University.)