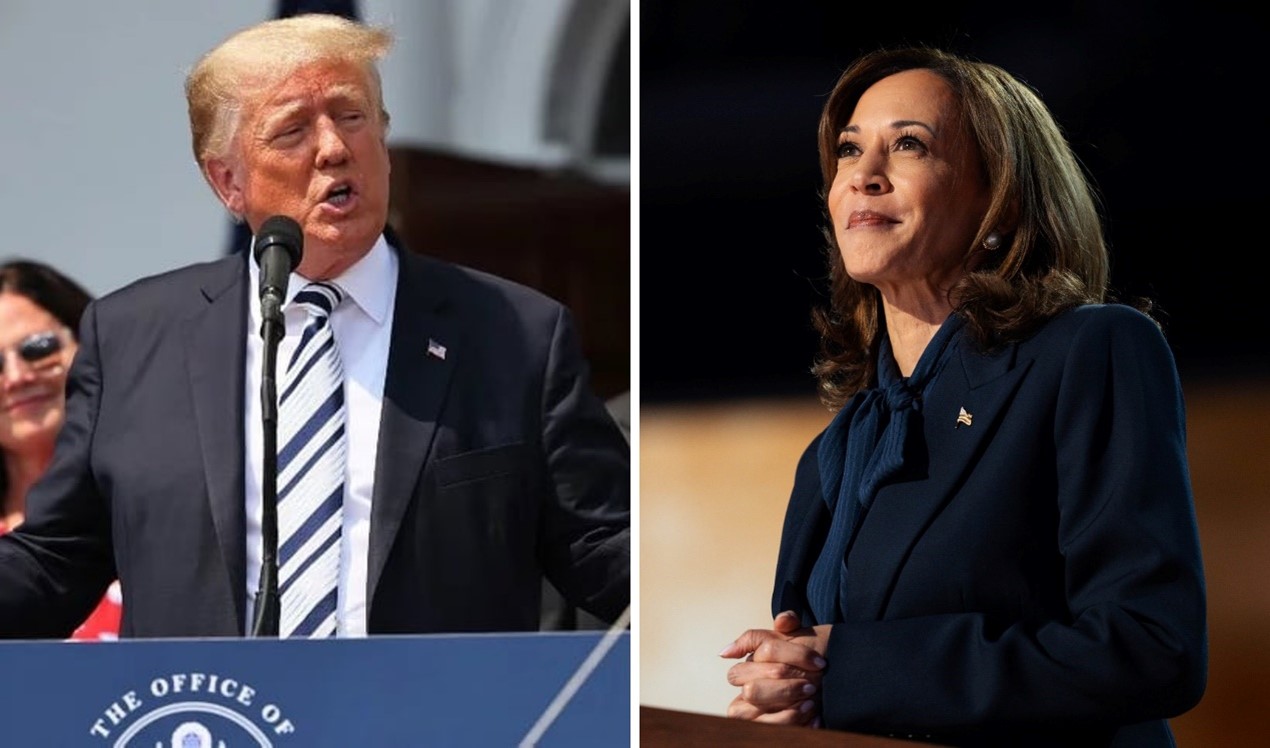

The title “Taiwanese Representative Office” in Vilnius deviates from the established China-approved practice of using the name of Taipei instead of Taiwan. Thus, while strong objections from China were not unexpected, especially harsh “gray-zone” economic sanctions took Lithuanian policy makers by surprise and stirred concerns within the EU. Picture source: Pixbay.

Prospects & Perspectives 2022 No. 10

Lithuania’s Unforeseen Asymmetrical Interdependence Trap with China

By Vida Macikenaite

February 25, 2022

In November 2021, Lithuania became the first European country to welcome Taiwan’s de facto embassy under the name directly referencing to Taiwan. The title “Taiwanese Representative Office” in Vilnius deviates from the established China-approved practice of using the name of Taipei instead of Taiwan. Thus, while strong objections from China were not unexpected, especially harsh “gray-zone” economic sanctions took Lithuanian policy makers by surprise and stirred concerns within the EU.

Economic coercion against Lithuanian industries

Two weeks after the Taiwanese Representative Office was opened in Vilnius, an unofficial campaign of economic coercion against Lithuanian industries was launched by the Chinese side. During the first days of December 2021, Lithuania was removed from China’s customs clearance system. Although the country appeared back on the system a few days later, that month Lithuania’s exports to China dropped 91.4 percent from the previous year. Exports from Lithuania’s only Klaipeda port have been suspended since.

Similarly, Chinese exports to Lithuania have been restricted, targeting Lithuania’s manufacturers. In 2020, Lithuania’s imports from China were worth 1.2 billion euros. Two thirds of those were industrial goods – various raw materials, components and microelectronic parts. Specifically this group of exports has been subject to delays and suspension at Chinese ports, while the movement of consumer goods and non-industrial goods continued. At the end of last year, it was estimated that 1,200 containers worth around 240 million euros were not able to reach Lithuania. Lithuanian companies source many intermediate products from China to produce other goods for export, and delay in shipment therefore obstructed production. Notably, some of those shipments had been prepaid, which could soon lead to significant shortage of working capital for the targeted local manufacturers.

Many in policy making circles and in the business community were astounded when reports surfaced that China was pressuring multinational corporations to cut links with Lithuania. After reports emerged that manufactured goods from EU countries —France, Germany and Sweden — that are dependent on Lithuanian supply chains were also subject to China’s import embargo, it was disclosed that China had pressured German car parts giant Continental to stop using components made in Lithuania. Lithuania’s garment manufacturers complained that their partners in the EU were cancelling orders due to pressure from China.

While a strong response from Beijing was expected, the degree of Lithuania’s vulnerability to economic measures from China was unforeseen. The debate in Lithuanian media prior to the opening of the Taiwanese Representative Office was leaning towards the consensus that due to the limited trade volumes, economic coercion measures in China’s toolbox were very limited against Lithuania. As it is now becoming clearer, the complexity of interdependence with China was underestimated. And the asymmetry in this interdependency has given Beijing great leverage.

China’s ‘measured’ response

China sought to warn Lithuania relatively early of the costs of extending more recognition to Taiwan. In May 2021, Lithuania officially confirmed it was withdrawing from the 17+1, framework of cooperation between China and countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Around the same time, the government indicated it was looking towards expanding relations with Taiwan. Against such developments, Lithuanian officials insisted that the country still adhered to a “one China” policy as defined in the joint communiqué between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Lithuania on September 14, 1991.

Nonetheless, Lithuanian businesses have reported that already in spring 2021, credit insurance was becoming unavailable for trading between Lithuania and China. In summer, China stopped imports of Lithuanian dairy, wheat and timber, and also suspended train freight services to Lithuania. According to some accounts, in September even fully paid Chinese exports China to Lithuania were significantly delayed at Chinese ports.

At the diplomatic level, China has actively sought to frame Lithuania’s policy as a violation of the “one China” policy (which Beijing refers to as the “one China” principle). At first, in August, Beijing recalled its ambassador to Lithuania and requested Lithuania reciprocate. Immediately after the opening of the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius on November 18, 2021, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs repeatedly stated that the case had violated the “one China” principle and called for Lithuania “to correct its mistake.”

The full-scale economic coercion campaign from the Chinese side was felt only from December last year. After China officially established that Lithuania had violated Beijing’s “one China” principle, unofficial economic sanctions followed.

In February, China’s General Administration of Customs officially announced a ban on beef and dairy imports from Lithuania, citing Lithuania’s failure to submit required documents. Other than that, economic measures against Lithuania have been unofficial. Reportedly, business partners in China never confirmed receiving any official directions from the state, and thus far no official confirmation of sanctions has come from the Chinese authorities. Moreover, as soon as the Lithuanian government raised the possibility of appealing to the European Commission for support, the country quickly returned to the Chinese customs clearance system and the reason for the problems with cargo to and from Lithuania turned to a “technical issue.”

The challenge ahead for the EU

The dispute between Lithuania and China has escalated to engulf the EU. European Commission Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis stated that Chinese measures against Lithuania constitute a threat to the integrity of the EU single market. As it responded to Lithuania’s call for support in the clash with the economic superpower, the EU requested WTO dispute consultations with China “concerning alleged Chinese restrictions on the import and export of goods, and the supply of services, to and from Lithuania or with a link to Lithuania” in late January, nearly two months after the unofficial sanctions against Lithuania began. Moreover, earlier, in December, the European Commission presented the proposal for a so-called “anti-coercion instrument,” which would give the Commission wide-ranging powers to impose punitive sanctions on individuals, companies and countries seeking to influence its political policies through economic pressure.

Such clearly defined measures would surely strengthen the block’s resilience and urgently need to be adopted. Yet, while some of the leaders of EU member states were quick to voice their support for Lithuania, others were more cautious. For example, Politico reported that Berlin feared the EU was becoming too aggressive in its defense of Lithuania against Beijing’s economic coercion.

Lithuania’s experience has exposed how far China is ready to go in using its economic leverage in the pursuit of its political objectives, thus underscoring the vulnerabilities of EU member states. While deep-seated economic interests within some of the EU member states prevail, the unavoidable challenge ahead for the EU is to agree on a long-term strategy on how the block can counter third parties’ attempts to exploit asymmetric economic interdependence against its members.

(Vida Macikenaite is Assistant Professor, International Relations Program, Graduate School of International Relations International University of Japan.)