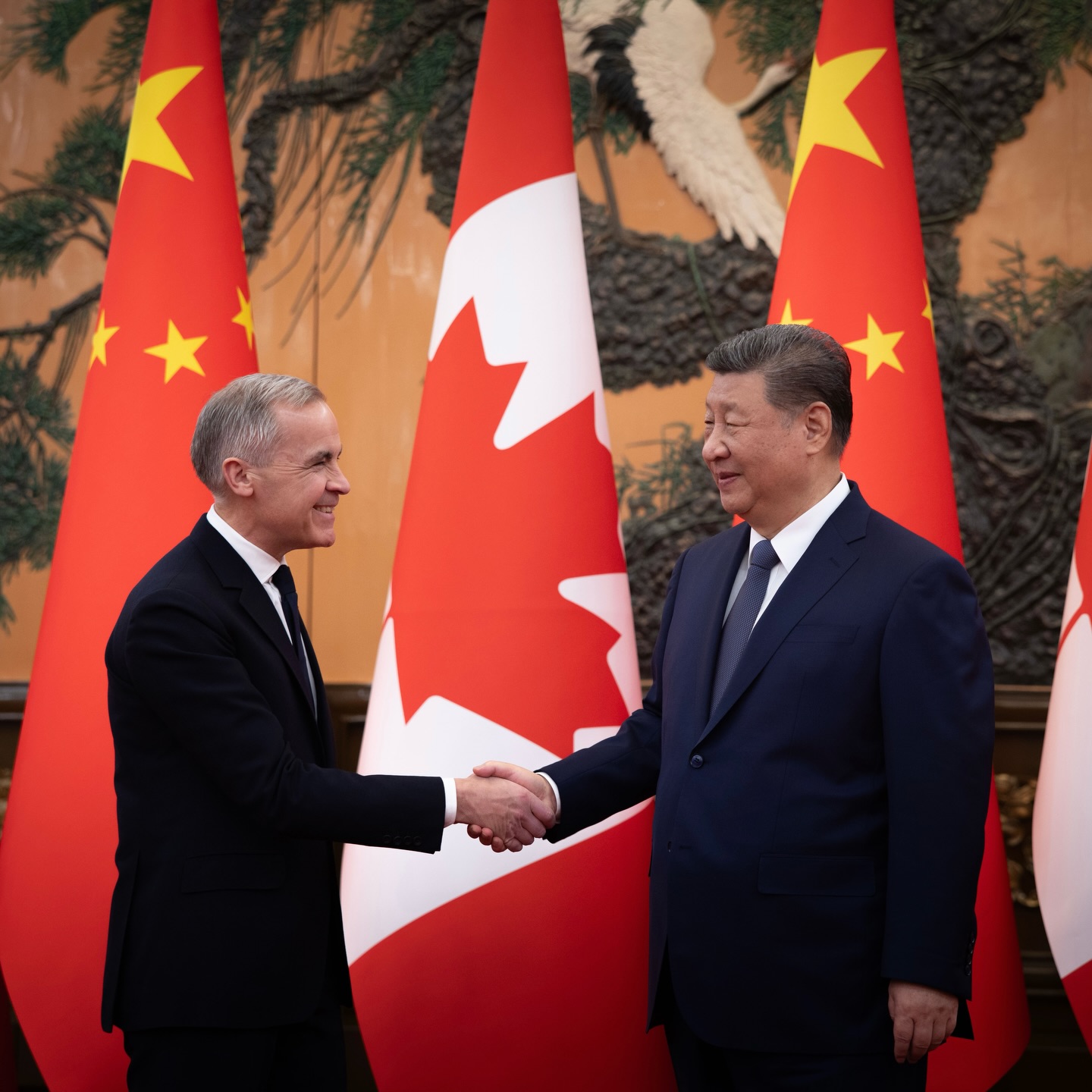

China’s sharp diplomatic and foreign policy edges never really went away, but may have been rested temporarily simply for reasons of expediency. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Has Xi Jinping Retired China’s

‘Wolf Warrior’ Diplomats?

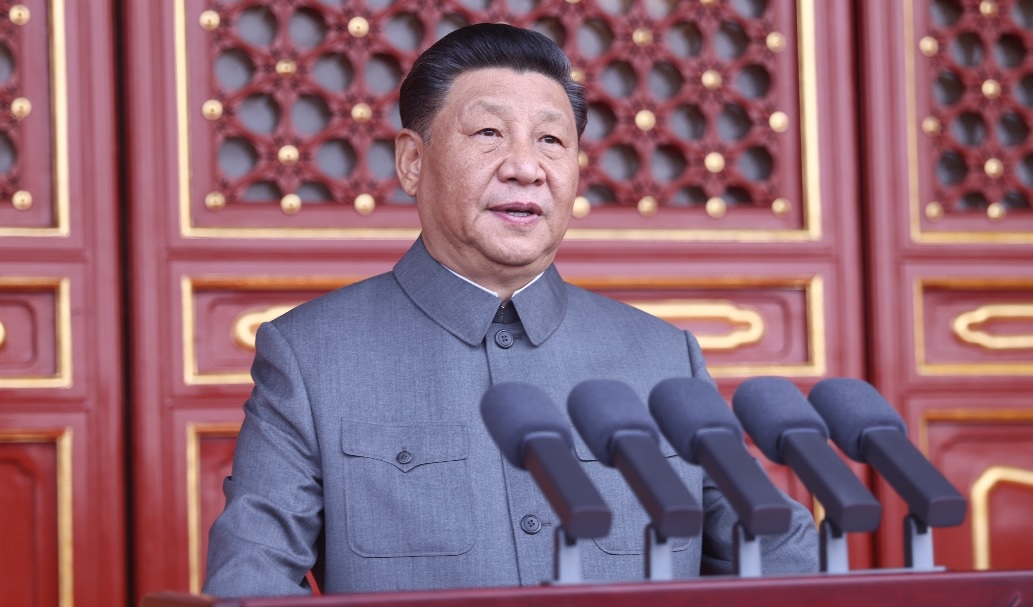

By George Magnus

The Chinese Communist Party’s so-called “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy is a bit like the old magician’s cliché: now you see it, now you don’t. This diplomatic riposte to criticism of the party and of China reached a high in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and of condemnation of China’s support for Putin. But pushback within China, and resistance and unpopularity outside it, led to a more emollient approach last year as Xi Jinping proclaimed he would promote a more “lovable” image of China.

Then came the latest row over the discovery and shooting down of an alleged Chinese “spy balloon” by the United States, and a resumption of some of the more familiar “Wolf Warrior” rhetoric. It is a timely reminder that China’s sharp diplomatic and foreign policy edges never really went away, but may have been rested temporarily simply for reasons of expediency.

Now you don’t see it

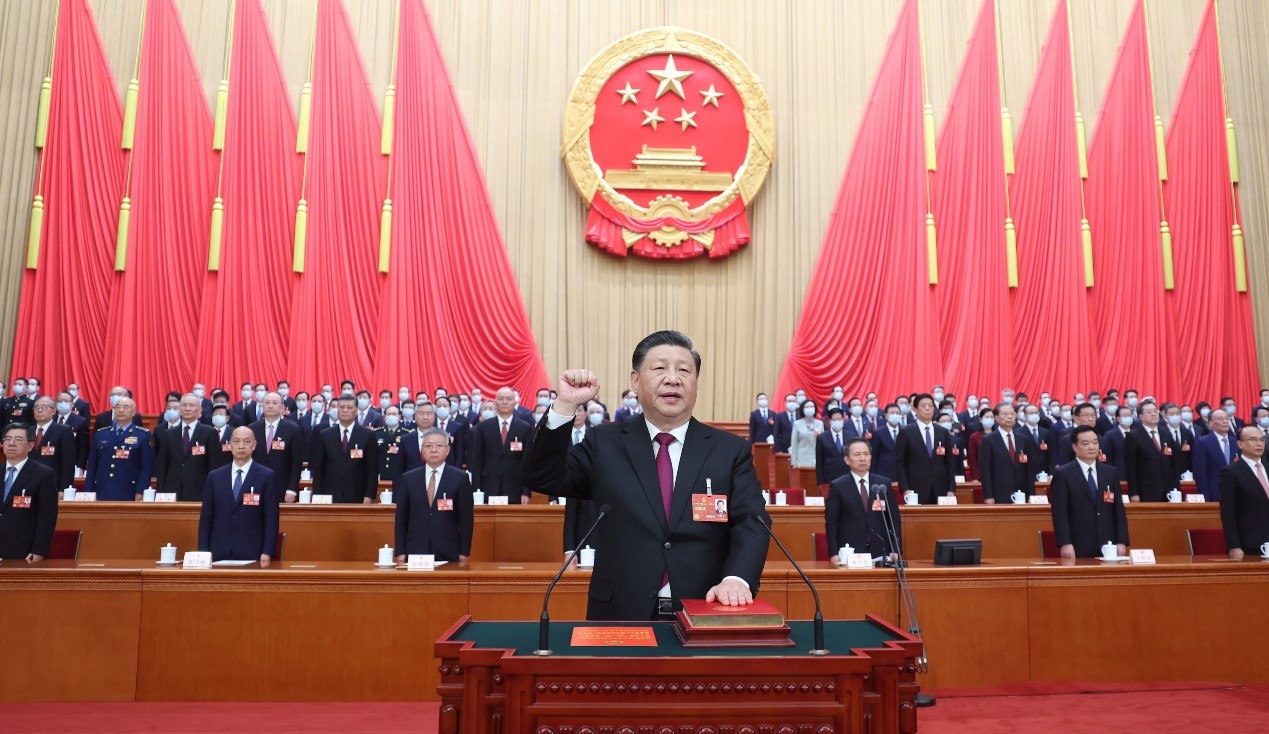

No one seriously expected the meeting between Xi Jinping and Joe Biden at the Bali G20 Summit last November to repair the bilateral relationship. Still, many thought a good outcome would be more cordial relations and the resumption of dialogue. For both, it offered a way to stabilize a poor relationship. For China it was also about a broader campaign to get China’s economy back on its sea-legs.

In addition to abandoning zero-covid, the government eased regulations and added stimulus in the beleaguered real estate sector, softened the harsh rhetoric and restrictions affecting many private firms and entrepreneurs, and tried to build back some confidence among foreign investors, and improve China’s badly tarnished external image.

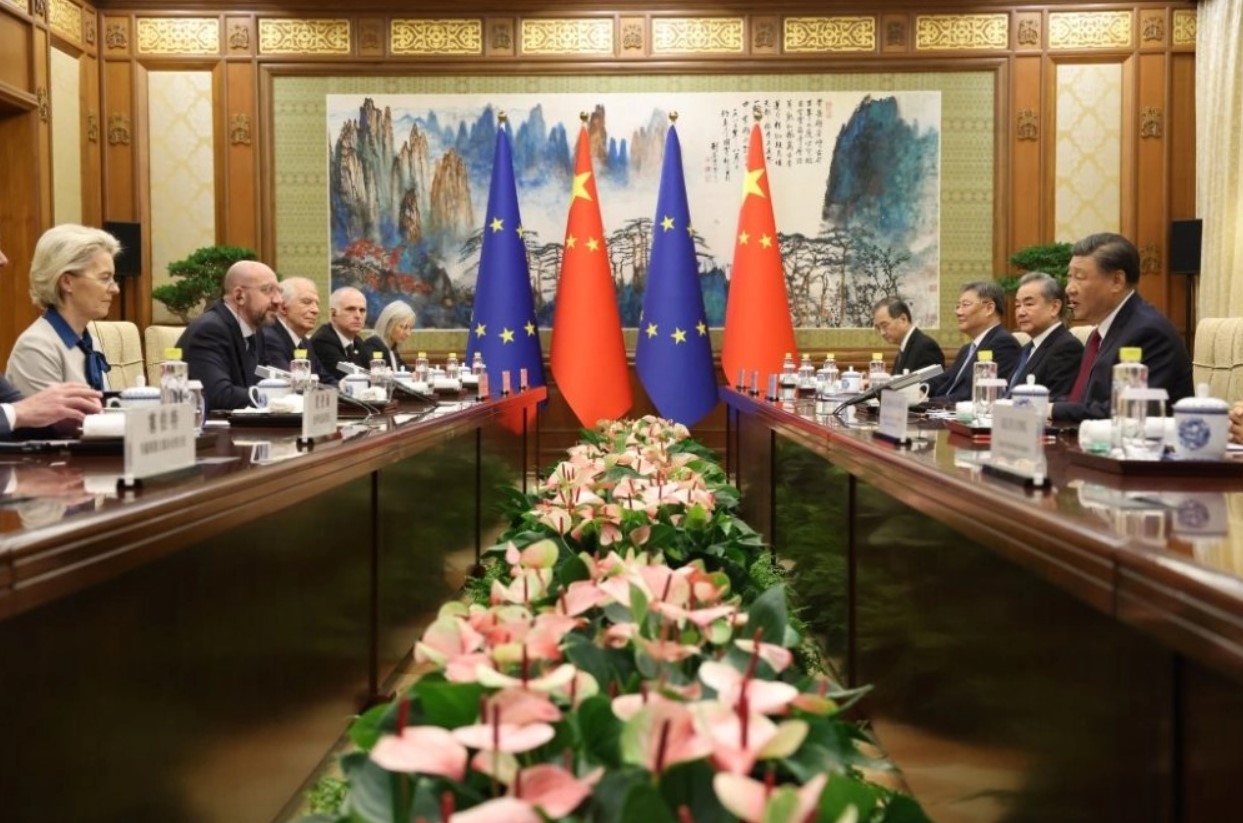

In the wake of Bali, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken planned to visit Beijing, but cancelled the trip after the balloon was discovered. Xi’s soon-to-be-retired economics guru and adviser Liu He addressed the crowd at Davos last month and met with U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who was also expected to visit China this year. The warmer atmosphere with the United States was extended to others. At and since Bali, Xi has meet with Australian Prime Minister Antony Albanese and Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong, and talks to rebuild frayed trade relations have been underway. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz lead a large delegation to Beijing in January, with both sides seemingly wanting to improve Sino-European relations.

Now you do

Yet, nothing was really changing — certainly not the Chinese government’s Taiwan policy, its militarization of the South China Sea, or its support for Putin. It is no surprise that China and the United States are again locking horns over the balloon incident, with China accusing the United States in effect of violating international law and Washington accusing China of violating its sovereignty. Perhaps the resumption of “Wolf Warrior” rhetoric was only ever a matter of what and when, because it is not so much an option as a feature of the way in which the CCP conducts international relations.

Indeed, the thin veneer over the suspension of “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy has been evident for several weeks. China suspended tourist visas for Japanese and South Korean citizens for a while in retaliation for these two countries requiring PCR testing for arrivals from China. It has warned Japan on a few occasions about the build-up in the latter’s defense capabilities and about disputed islands in the East China Sea. It has warned several Asian countries to be vigilant about being “used” by the United States, after the latter had agreed with the Philippine government to acquire several new bases. It has given notice about its territorial, maritime and fishing rights in the South China Sea that intrude on exclusive zones also claimed by Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei.

In Eastern Europe, Estonia and Latvia angered China last August by following Lithuania out of the 16+1 group that China founded to expand its influence in Europe. This year, Beijing delivered a warning to Czech President-elect Petr Pavel, following the latter’s telephone call with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, whom he has said he intends to visit in future. A foreign affairs ministry spokesperson is quoted as saying that Pavel trampled on China’s red line and hurt the feelings of the Chinese people. Meanwhile, relations with India are simmering while both countries contest an ill-defined, 3,440km disputed border in the Himalayas, ostensibly about infrastructure and water but symbolic of a deeper geopolitical rift.

Wolf Warriors can’t rest for long

These and other tensions underlie China’s foreign policy agenda in pursuit of a change in the global governance system that better suits Beijing’s interests. The Global Development and Global Security Initiatives, which build on the pre-existing Belt and Road, are labels that do not convey obvious threat. Yet, they do promote a CCP alternative to the liberal democratic capitalistic model and countries are ‘invited’, or rather expected, to align with China their trade, and technology standards and equipment on the one hand, and security, surveillance and intelligence on the other.

This agenda, along with China’s spirited defence of it and criticism of its antagonists runs through, for example, its human rights and other initiatives and resolutions in the United Nations and its organizations. It also frames China’s desire to build alternative security organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and alternative financial arrangements, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and attempts to sanction-proof itself through setting up its own international payments, clearing, swap and currency denomination strategies.

The aftermath of the balloon incident and prospects for Blinken’s visit may depend on China’s own political calendar — with the important “twin meetings” in March, and also that of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who has signaled his intention to visit Taiwan sometime this year. In the end, however, coercive diplomacy requires other states and commercial entities to not offend or disagree with China, or better still to support its narratives and goals. Wolf Warriors can never be rested for long.

(George Magnus is a Research Associate at Oxford University’s China Centre and a Research Associate at SOAS, London.)