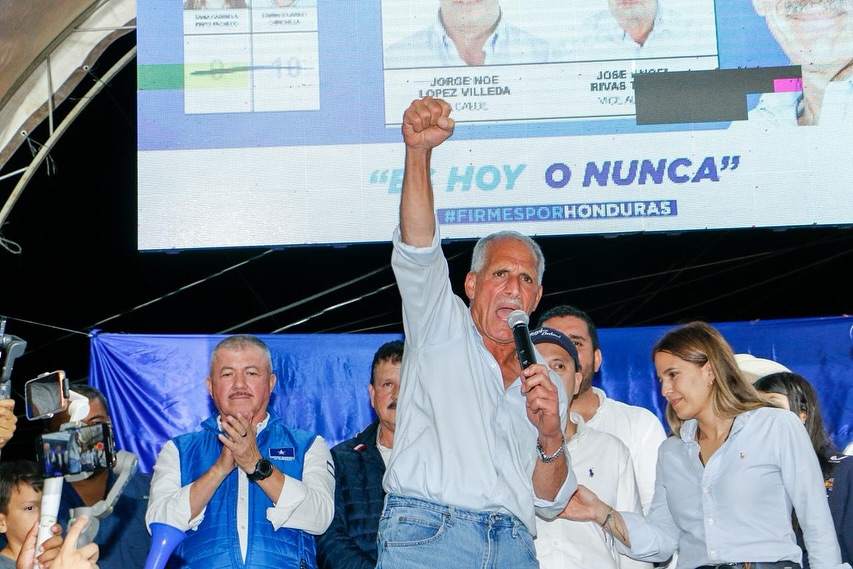

The 2025 edition of the end of year summit season in Southeast Asia concluded largely without mishap. U.S. President Donald Trump seemed to take no issue with the meeting in Malaysia, even appearing to enjoy the pomp and circumstance his Malaysian hosts prepared. Tense U.S.China relations did not overshadow the summitry. Picture source: ASEAN, October 26, 2025, ASEAN, https://asean.org/secretary-general-of-asean-attends-the-opening-ceremony-of-the-47th-asean-summit-and-related-summits/.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 69

The ASEAN Malaysia Summit: The Calm Before the Storm?

By Ja Ian Chong

The 2025 edition of the end of year summit season in Southeast Asia concluded largely without mishap. Leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members and their dialogue partners likely heaved a collective sigh of relief at the conclusion of the meeting in the Malaysian city of Kuala Lumpur. U.S. President Donald Trump seemed to take no issue with the meeting in Malaysia, even appearing to enjoy the pomp and circumstance his Malaysian hosts prepared. Tense U.S.-People’s Republic of China (PRC) relations did not overshadow the summitry. Under the threat of increased U.S. tariffs, Cambodia and Thailand even made a joint declaration to de-escalate their border differences that turned violent several months prior. Malaysia even walked away with economic agreements with the United States.

Lingering challenges

Seeming success, however, obscures the continuing challenges facing ASEAN in an era of intensifying major power competition and declining major power attention to prevailing international institutions, laws, and norms. Several months before, in the face of sweeping U.S. tariffs, ASEAN economic ministers agreed over video conference to work on facing challenges to trade jointly. Working together, even collective bargaining, makes sense for ASEAN member states. With the partial exception of Indonesia, ASEAN member states are small- to medium-sized economies with limited leverage. Together, they managed key raw materials, oversaw supply chains, and had a total market size of 700 million people, potentially generating significant leverage. Yet, given U.S. warnings about working together and individual country interests to have a tariff rate that undercut their neighbors’, ASEAN members went ahead to cut bilateral deals with the United States.

President Trump went to Kuala Lumpur to preside over the ceremony for the Thailand-Cambodia peace deal, claiming at the time to have ended eight wars. That arrangement started fraying after the ink was barely dry. Thailand announced on November 11, 2025, that it would begin rearming in preparation for renewed hostilities following the injuring of Thai soldiers by landmines Bangkok claimed Phnom Penh had newly installed in disputed areas. The Trump administration has again threatened tariffs if escalation does not stop. That ASEAN was challenged to hold a truce together once attention from the U.S. administration shifted elsewhere should be unsurprising. Neither Phnom Penh nor Bangkok saw ASEAN as the primary venue for brokering de-escalation despite calls by Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and only did so under the threat of U.S. tariffs. Other ASEAN leaders and capitals were also surprisingly silent in response to Malaysia’s call for negotiations as this year’s rotating ASEAN chair.

There was scant mention of the civil war in Myanmar even though the breakdown of governance created conditions supportive of the online scam rings plaguing Southeast Asia and beyond. Escalating tensions between member state the Philippines and the PRC over their territorial dispute in the South China Sea went largely unmentioned with continued promises of progress over a Code of Conduct governing behavior in that body of water. Despite outward shows of solidarity, some ASEAN capitals blame Manila for upsetting Beijing and creating unnecessary tumult in the region.

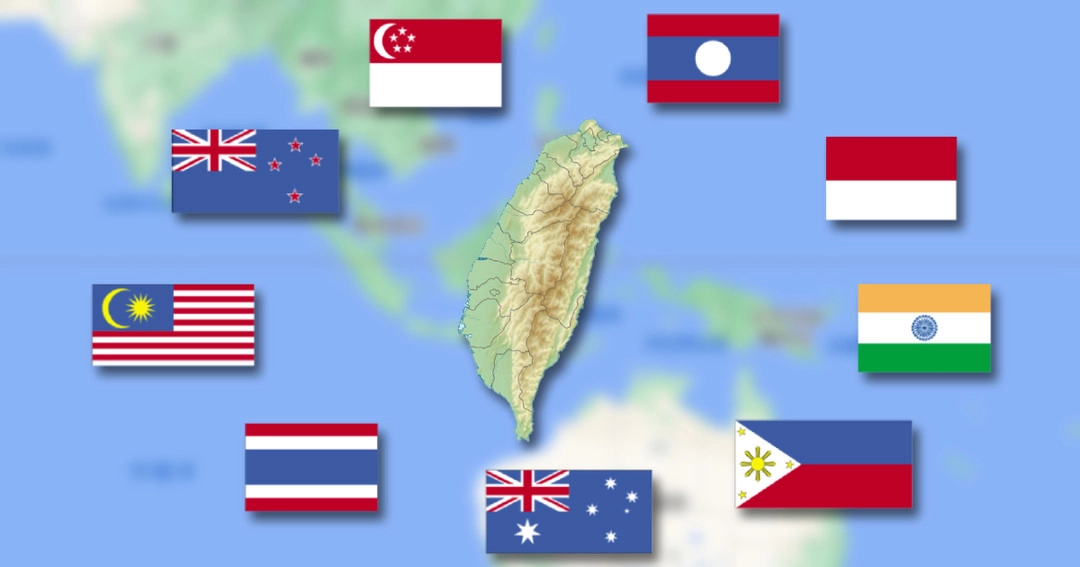

Despite the growing risks of spillover from potential escalation over Taiwan, the flashpoint remained officially ignored during the summit meetings. Official thinking in the region seems to be that someone else will take care of any problems pertaining to Taiwan’s security and stability, allowing regional states to free-ride on any benefits.

The U.S. and a region in flux

As part of President Trump’s visit to Malaysia, the Southeast Asian country signed two separate agreements with the United States over trade and rare earths. These appeared at the time as triumphs for Malaysia’s opportunistic use of the ASEAN framework to advance its bilateral interests. Cambodia too concluded a trade deal with the United States. However, Beijing soon came to press Putrajaya and Phnom Penh about the nature of the agreements to ensure that they did not impinge on PRC interests. By late November, Anwar Ibrahim’s Madani government had to assure Beijing that its arrangements with Washington would avoid affecting PRC concerns. Almost concurrently, Anwar’s longtime political rival, erstwhile ally, and former Malaysian Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad, lodged a police report over the deals with the United States.

Developments leading up to and following from the ASEAN and related summits in October and November 2025 point to continuing concern about the grouping’s cohesiveness and relevance. ASEAN still retains an ability to convene meetings bringing together major actors. It is also able to maintain its ability to work on existing free-trade frameworks like the Regional Cooperative Economic Partnership (RCEP) framework. However, member states seem unable to pull together on collective bargaining over economic issues or higher-end economic cooperation. Consequently, some ASEAN members are investing in alternative arrangements such as BRICS and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which others are unable or unwilling to join. Some ASEAN members appear to be drawing closer to Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the U.S. on a range of issues, including security, even as others seek closer cooperation with the PRC or a greater diversity of partners. Intra-ASEAN cooperation appears to hold lower a priority for member states. Divergent patterns of collaboration raise questions about the degree to which ASEAN can hold together and manage regional stability at a moment of strategic stress.

Susceptibility to pressure, especially from major powers, sends a signal not of flexibility but of inviting greater demands and even coercion. Rather than being able to play major actors or inviting a competition for favors, what appears to be pandering to the powerful may put Southeast Asian states in positions where they are increasingly squeezed from different sides. Absent a clear idea of when and how much to let go of a position, the risks of supposed “hedging” behavior become more pronounced when major powers become less accommodating of vagueness and insufficient commitment. Claiming neutrality without investing sufficiently in defense may place Southeast Asian states in situations more like Belgium before the two World Wars and Cambodia in the early 1970s rather than Switzerland. An impression of swaying in the face of pressure in Southeast Asia creates doubt over any commitment to cooperation by reinforcing a view that a partner may be quick to cut and run at the first sign of trouble rather than to stick to a promise.

Long-term risks

The latest edition of ASEAN summitry suggests on the surface that the grouping’s member states and the region dodged major trouble — and even gained a new member in the form of Timor Leste. A deeper reading of events suggests that short-term issues were successfully swept aside for the time being. However, ASEAN and its members continue to face significant longer-terms risks both from rising major power rivalries and from ASEAN mechanisms that developments across the region and the world fast outpace. Much as ASEAN elites and leaders recognize the challenges facing the organization in a more contentious world, overcoming collective action problems, inertia, mutual distrust, and over-conservatism appear to remain out of reach. Such realities place ASEAN, its members, and people across Southeast Asia at greater risk when cooperation is key and major powers are far less tolerant of actors who do not toe their respective lines. These trends portend more trouble for Southeast Asia and ASEAN going forward.

(Dr. Chong is Associate Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore.)