The French and UK Elections: What Do They Mean for their Foreign Policy

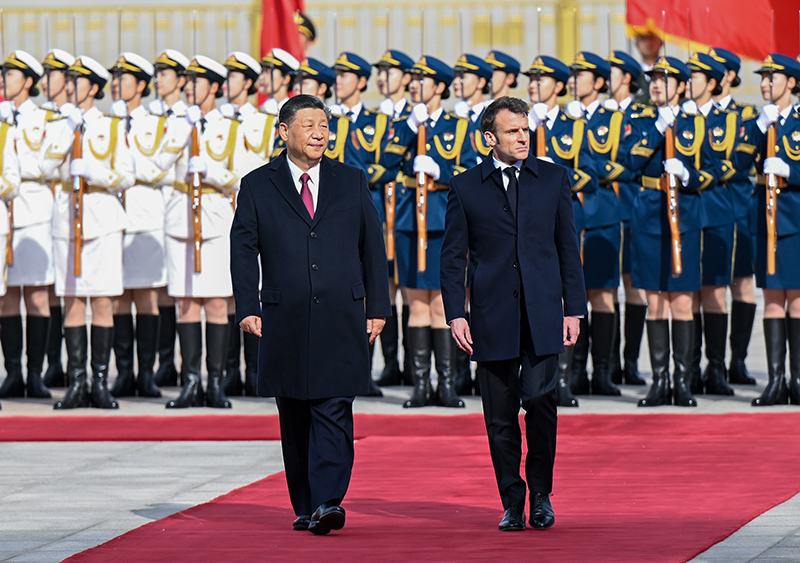

The elections in the UK and France have not radically shaken up the foreign policies of either country. Macron is still in charge albeit in a weaker position domestically. Starmer, will pursue the same interests and uphold the same values internationally as previous UK governments have. Picture source: Emmanuel Macron, June 15, 2020, Facebook, <https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2785474408351794&set=a.484020503079871&locale=zh_TW>; Keir Starmer, July 5, 2024, Facebook, <https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=1063568918473941&set=a.514634893367349>.

The French and UK Elections:

What Do They Mean for their Foreign Policy

By Gray Sergeant

On May 22, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak stood outside No.10 Downing Street and, as he got soaked by the rain and drowned out by protesters, announced a general election. His campaign then ran into calamities. Quite why French President Emmanuel Macron sought to emulate his British counterpart is a mystery — but he did. Hours after his party got a drubbing in the European Parliament elections, the French president dissolved the National Assembly. If the polls were to be believed, both leaders were taking a huge gamble.

For Sunak, the move did not pay off. On the July 4, fourteen years of Conservative rule came to an end with a landslide victory for Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Party. For Macron, the result was less devastating. While the Far Right did well in the first round of voting and looked set to secure a majority, in the second round they were pushed into third place. Nevertheless, it was the Left alliance, the New Popular Front, which claimed the most seats. Macron’s Ensemble fell into second place, securing 159 seats, down from 245 two years ago. Unlike the British Parliament, where Labour now has nearly two-thirds of the seats, no one single party, or bloc, has an overall majority.

All of this will have consequences for both countries’ foreign policies. These are two countries that are Europe’s preeminent players on the global stage, what with their permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council, possession of nuclear weapons, and long traditions of active engagement on major international issues.

France: The Centre Folds

Macron, of course, remains president (his term does not come to an end until 2027) and in the French system it is the president who leads foreign policy. He is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and retains the prerogative to ratify treaties. Yet the result weakens his position domestically and gives the divided parliament control over allocating budgets, including future defence budgets.

The Far Left challenges orthodox European foreign policy thinking on NATO, the European Union (EU) and Ukraine just as much as the Far Right. That is, leaders of these movements have traditionally opposed the transatlantic alliance, continental integration and more recently have sounded skeptical about continued support for Kyiv. In March, for example, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a key figure in the New Popular Front, led parliamentary opposition, in a symbolic vote, to Macron’s security agreement with Ukraine. Meanwhile, more recently, the flagbearer for the Far Right, the National Rally’s Marine Le Pen, has signaled her party’s intention to constrain the level of aid Macron can send to the conflict.

Both extremes profited at this election, with the Far Right winning more votes than any other political bloc, and thus doubts have emerged about the long-term direction of French foreign policy. Le Pen may have been beaten in the 2022 presidential run-offs by 17 points, but this margin of defeat was down from 32 points four years earlier. In 2027 the anti-Far Right bloc may falter. Naturally, the question asked by allies and partners around the world is: can we count on Paris?

Britain: Becoming Good Europeans

London, perversely, now looks like a model of reliability. The Tory wars, which brought a series of new prime ministers to power in quick succession, are over and with this the UK can properly move on from the many years spent grabbling with its exit from the EU. Restoring relations with European partners is at the top of Starmer’s agenda.

Like previous British prime ministers, he has put on record his steadfast support for Kyiv. However, unlike his immediate predecessors, Starmer hopes to repair post-Brexit fractures with the EU and key European partners. The newly announced Strategic Defence Review promises a “NATO first” reappraisal of the UK’s armed forces. The possibility of a British-European foreign and security pact has also been mooted, together with a special defense deal with the Germans. Alongside this (or perhaps, in exchange for this), Labour will hope to cut deals on refugees and trade, to resolve problems which have emerged after the UK exited the EU.

The extent to which this will come at the expense of engagement with the rest of the world, particularly the Indo-Pacific, remains to be seen. Initially the Labour shadow front bench was highly critical of the previous government’s “tilt” to the region, articulated in the 2019 Integrated Review. Yet they have come to support the products of this policy, including major initiatives like the AUKUS partnership with the U.S. and Australia. While a Labour government might not tilt further a reversal seems unlikely.

More continuity than change should also be expected in terms of China policy. Despite promising to conduct an audit of bilateral relations, the new foreign secretary David Lammy’s three Cs for dealing with the People’s Republic (challenge, compete, cooperate) sound very similar to the previous government’s mantra of protect, align, engage.

Finally, the new government, as successive UK governments have, will seek to maintain, and strengthen Britain’s paramount partnership with the U.S. The anti-Americanism of Starmer’s predecessor Jeremy Corbyn, whose foreign policy views were an aberration in Labour politics, is long gone. Lammy speaks warmly of his time living in the U.S. and the importance of transatlantic ties. He also boasts of his bridge building efforts with prominent Republicans, including the newly picked vice-presidential nominee J.D. Vance (connections which might compensate for his past criticisms of Donald Trump).

The elections in the UK and France have not radically shaken up the foreign policies of either country. Macron is still in charge albeit in a weaker position domestically. Starmer, a traditional Labour politician, will pursue the same interests and uphold the same values internationally as previous UK governments have. Although, now the emphasis will, undoubtedly, be on proving that Britain can be “a good European,” and France’s recent election makes this job easier. The key change brought about by this month’s results is these countries’ reversal in the reliability rankings. Now, when it comes to seeking regional, even global, leadership in the long-term it is London, rather than Paris, which seems the better bet.

(Gray Sergeant is a Research Fellow in Indo-Pacific Geopolitics at the Council on Geostrategy, UK.)