As Russia and China grow closer, we may experience the peak of their “no limit” friendship, however, both are the powers that are striving for global hegemony in the West-clouded world. This competition for the sphere of influence and increasing power asymmetry may restrict the long-term alliance in future.

Picture source: Depositphotos.

The Sino-Russia Axis after the Munich Security Conference

By Kritika Rajput & Siddhartha Ghosh

The 60th edition of the Munich Security Conference 2024 (MSC), which focuses mostly on transatlantic security policy and European defence, was held in February. This time the discussions were dominated by the Russia-Ukraine war and the Israel-Hamas conflict. The talks emphasized finding measures to reduce the tensions and find a peaceful closure to this ongoing Russia-Ukraine crisis. Amid this, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi defended China’s relations with Russia and warned the West to not cross its “red line” over Taiwan, even though it claims itself as a neutral country in the conflict. Last year at MSC, China had also emphasized the implementation of the Minsk Agreement — signed by Ukraine, Russia, and the OSCE special representative in September 2014, negotiated under the auspices of the OSCE, Germany and France.

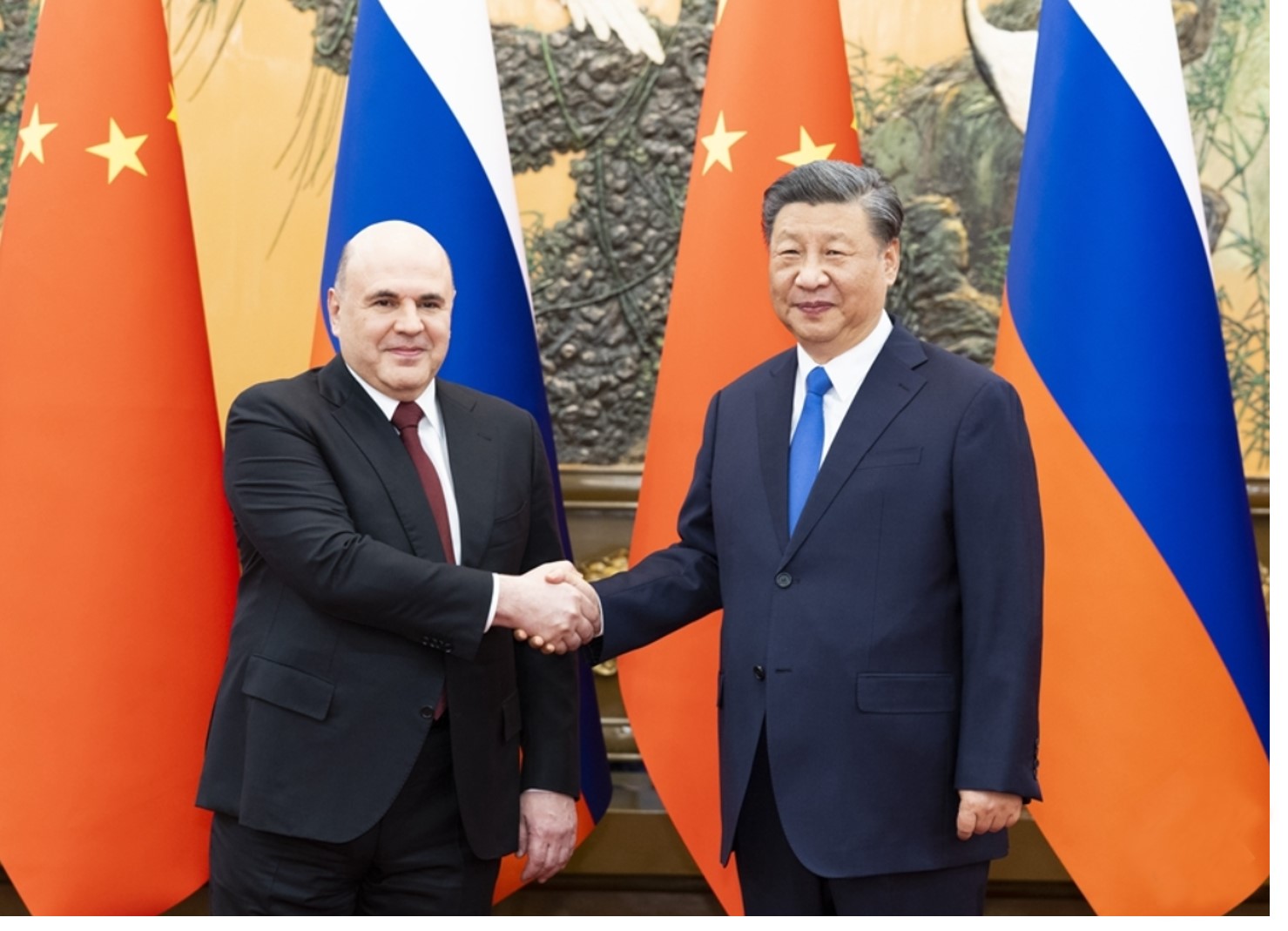

Sino-Russian relations are an example of a great power alliance based on realpolitik, rather than just an autocratic alliance. Although Sino-Russian relations have been in the making for four decades, they have recently gained more attention due to China’s continuous support of Russia after the invasion of Ukraine. During their February 2022 summit, Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a “no limits friendship,” which signaled an unprecedented level of camaraderie between Beijing and Moscow. Despite occasional divergent interests highlighted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China aligns with Russia, as their relationship is based on mutual interests

Factors behind China’s support to Russia

China views the crisis between Russia and Ukraine as a case of “two brothers” fighting each other, which means that would be best if the outside world left them to handle their own affairs. China’s decision to support Russia in Ukraine crisis could ostensibly be driven by strategic concerns regarding Taiwan. By exhibiting solidarity with Russia, China might be seeking assurance that Russia would reciprocate support in any potential conflict over Taiwan. This alignment could potentially fortify China’s position by deterring interference from other global powers. Additionally, China is learning from the Russian case how to maneuver the Western sanctions in case of cross-Strait conflict.

However, in the end, Taiwan is not Ukraine and China is not Russia. Although it is appealing to draw comparisons between Taiwan and Ukraine, the two are distinct nations operating under different geopolitical contexts. Additionally, the domain of geopolitics is unpredictable. China prioritizes its economic relations — unlike Russia, which went all in to take the economic risk. Despite the recent military activities beyond its borders, China has remained cautious and has refrained from engaging in large-scale combat operations or engaging in massive invasions of other sovereign nations and instead conducted small-scale skirmishes along the Indian border and the South China Sea, in contrast to Russia, which has involved itself in major military conflicts along its Eastern borders.

Another driving force behind Sino-Russian ties is the personal rapport between the two leaders and their agreement on domestic and global governance issues. However, despite this, Beijing has endeavored to resist Russia’s attempts to draw it deeper into supporting the war and the broader Chinese bureaucracy remains more skeptical of Moscow’s actions.

Sino-Russian relations reaping benefits of Ukraine crisis

After his big speech at MSC, recently, Wang Yi again showed clear support for Russia, saying that Russian natural gas was fueling Chinese households, while Chinese cars were driving on Russian roads, showcasing the increasing bilateral trade between the two. Two years after Ukraine crisis, due to the thriving Moscow-Beijing trade relationship, Russia’s external trade has stabilized, with imports bouncing back to 2019 levels after a significant initial dip. Since the conflict in Ukraine, Russia has increased its gas supplies to China, which has helped Russia survive the financial blow of declining shipments to Europe due to sanctions. Last year, China sold over 841,000 vehicles to Russia, making it the largest export market for Chinese automakers, filling the void left by restrictions of the European Union. Also, shipments of dual-use equipment and industrial products from China have undeniably bolstered Russia’s war effort.

These may look like good figures, but they also show that Russia is becoming overly dependent economically on China for trade amidst the Western sanctions. This will increase the economic power asymmetry in favour of China, a situation that Russia would want to not let stretch for too long.

What the future holds for ‘no limit’ friendship?

As Russia and China grow closer, we may experience the peak of their “no limit” friendship, however, both are the powers that are striving for global hegemony in the West-clouded world. This competition for the sphere of influence and increasing power asymmetry may restrict the long-term alliance in future. Despite Russia being the largest trading partner for China, it does not feature among the top 10 countries in terms of imports to China and holds only the 10th position in Chinese exports. This indicates that the economic relationship between the two countries, while significant, is not as dominant in China’s trade landscape as it is with other countries. It is highly likely that in the long term, the West will continue to be China’s primary trade partner due to various factors such as market size, technological advancements and investment flows.

Another reason that may affect Sino-Russian relations is China’s increasing involvement in Central Asia and the Arctic region. These areas have traditionally been considered a sphere of influence by Russia, and China’s growing economic power and influence could be perceived as a challenge to Russia’s interests in the region. Also, Russia would not want any competition in its sphere of influence from any ostentatious economic power like China.

Although there has been an increase in joint military exercises, there seem fewer chances of both countries going into a military alliance as both would want to maintain the status quo in their relationship and cannot let the other have the upper hand in this mutually beneficial relationship. Furthermore, their relations are facing complications as last year, China released its “New Standard Map” in which it claimed an island in Eastern Russia along the border with China, increasing the tensions between the two. The map used the Chinese names of eight cities, including Haishenwai for Vladivostok. On the other hand, the recently leaked decade old secret documents from the Russian military indicate the training scenarios and use of tactical nuclear weapons in case of a hypothetical invasion by China. Training also considered how China is fueling the unrest in the Far East by paying protesters for clashes with Police. The leaked documents revealed the deep suspicions of China among Moscow’s security elite.

Furthermore, despite Russia’s current focus on Asia, it has its long-term interest in Europe, given its cultural orientation towards Europe than China or Asia. Additionally, Russia has established relations with several prominent Asian countries such as India and Vietnam, among others, who are significant buyers of Russian weapons and these countries have strained relations with China, implying that Russia would not want to jeopardize its standing as a reliable defence partner of these countries, given its existing ties with China. On the other hand, China would also not want to over-depend on Russia and may seek to mend its strained relations with European markets for exports and BRI projects.

(Kritika Rajput is Research Associate; Siddhartha Ghosh is Head, Research and Outreach, Red Lantern Analytica.)