In June 2023, China passed a Foreign Relations Law (FRL) governing the broad spectrum of international relations and external interactions. Any foreign firms or citizens doing business in China will need to assess not only business and political risk conditions inside China as they normally would and do, but also how they themselves might be affected in the light of new political risks arising between China and their own countries of origin. Picture source: Depositphotos.

China’s Sweeping New ‘Foreign Policy Law’: Scope and Implications

Prospects & Perspectives No. 39 July 13, 2023

By George Magnus

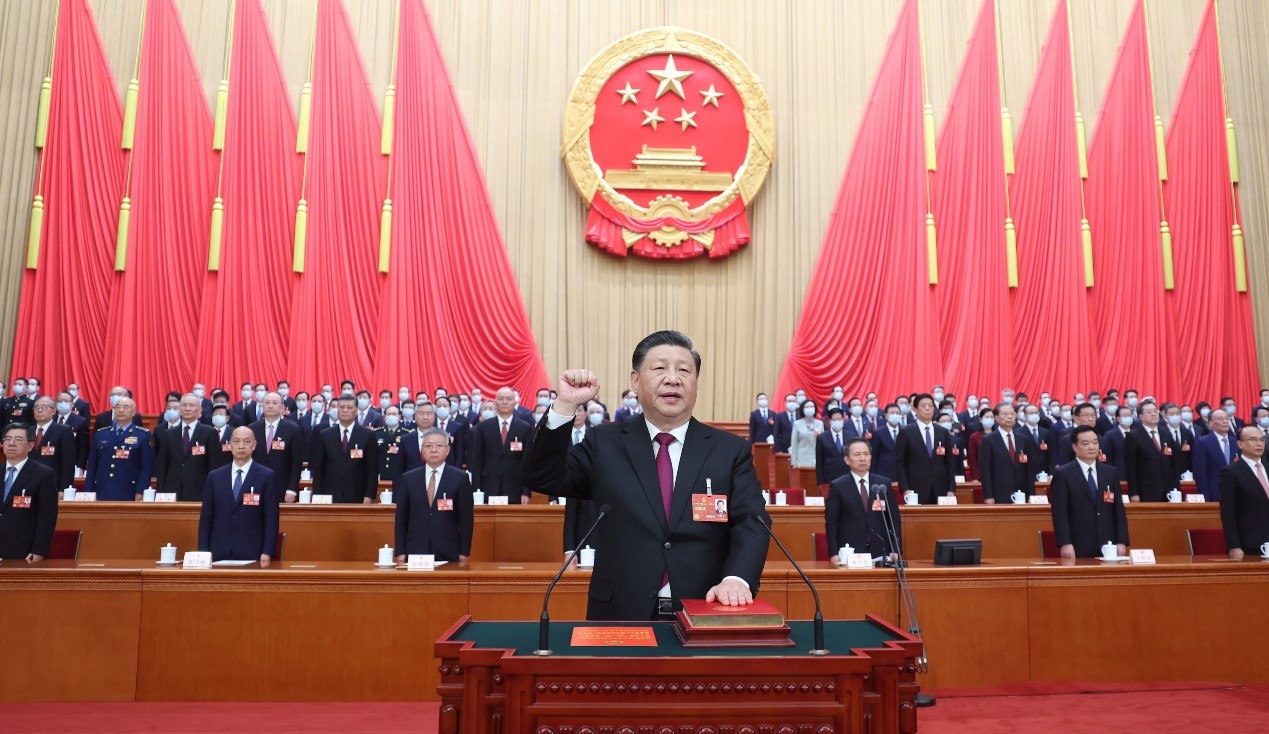

In June 2023, China passed a Foreign Relations Law (FRL) governing the broad spectrum of international relations and external interactions. While liberal-leaning democracies with separate and independent branches of government determine international relations rules and jurisdiction in different ways, China’s FRL formalizes these and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) mandate in matters affecting global governance and international security.

The FRL does not set out to flout international law, and indeed, the Chinese government is keen to set out its credentials as a responsible power in international relations. The existence of the law implicitly acknowledges, however, that the international law construct as it currently stands may not always align well with how the CCP sees its own interests. It acknowledges, for example, that China should fulfill “in good faith” its obligations under international treaties and agreements, specifically the Charter of the United Nations and other constructs in the international system. In theory, at least, this could mean that China might, having signed up to international treaties and agreements, subsequently resolve that under Chinese law there were parts that were not made in good faith, and should not apply.

The party’s toolkit

The six chapters of the new legislation stipulate the purpose and circumstances under which Chinese law will apply in foreign relations, including extraterritorially, and provide for measures to take actions against foreign countries, organizations and individuals. Article 1, for example, says that the law is designed to safeguard China’s sovereignty, national security and development interests; protect and promote the interests of the Chinese people, including abroad; and build China into a great modernized socialist country.

The law also provides for the enactment of measures, in line with China’s assertion of the principle of a multipolar (as opposed to the current U.S. or G7 type) system to advance the Global Development, Security and Civilization Initiatives, which have all become part of the CCP’s international relations agenda to build a “community with a shared future for mankind” under which China wants other nations to align with its governance practices and interests. The FRL also spells out what China means by “human rights,” confirms its commitments to global environmental and climate governance, and refers to its handling of foreign aid and grants on the basis of sovereignty. Quite what the last of these provisions means for, say, Ukraine, is not, however, at all clear.

It is a moot point, therefore, whether the FRL is perhaps intended more for the domestic than a foreign audience.

The latter might seem a less likely target, because no one outside China has any doubt that the CCP is in charge of international relations. On the other hand, Western analysts have raised concerns about the ways in which the system of law under the FRL will be used to advance the CCP’s specific interests, for example, with regard to foreign investment.

Questions abound

Some worry about the consequences of attempts to strengthen the implementation and application of laws and regulations in foreign-related fields on the basis of national sovereignty, security, and development interests. This might, for example, include restrictive measures against entities or individuals deemed to have “endangered” or harmed Chinese national interests. The law gives the government in effect the right to take action against foreign parties either under existing Foreign Investment law or if such parties should apply sanctions against China.

By and large though, there isn’t really much in the FRL that opens up new or material threats to foreign parties that either do not exist already or are not regarded as existing parts of the CCP’s international and diplomatic toolkits.

For Chinese institutions and individuals, on the other hand, the FRL aggregates and puts in one place several basic principles enshrined in other laws and documents. It is a sort of umbrella piece of legislation that includes but goes beyond the Anti Foreign Sanctions Law passed in 2021 and this year’s Anti Espionage Law. The latter was recently cited as the basis for actions taken against American due diligence firms and some employees in China, and to assert the government’s opposition to the sharing of data and information about Chinese companies.

‘Long-arm jurisdiction’

Ostensibly, the FRL provides the legal context in which China can fight back against sanctions, and any other form of intervention by foreign governments or what it calls “long-arm jurisdiction,” but also gives the government formal ways of asserting rights, for example in the South China Sea, or over Taiwan — or indeed anywhere else over any significant matters of international governance that it considers antagonistic or intrusive.

The FRL is liable to underscore uncertainties in international relations in which governments will have to weigh more carefully what Beijing might or might not consider in good faith. It also means that already anxious investors who put money to work in China either in factories and offices, or in portfolio assets, will have little reason to expect any meaningful improvement in the legal and governance certainty and predictability which are key to their confidence in China.

Indeed, foreign firms and citizens in China will have been reminded that they will have to be increasingly vigilant about actions the party might take to counter or retaliate against any decisions which it deems to be injurious. They will have to remain alert to any business dealings or agreements with partners in which, for example, Taiwan is referred inappropriately, or there might be references to human rights and Xinjiang, or other provisions covering data, technology or anything deemed counter to national security and honor.

Small to medium size firms in particular will most likely conclude, public rhetoric notwithstanding, that they will have to continue to de-risk or decouple incrementally since the once-manageable idiosyncrasies of operating under CCP governance in China’s dynamic market are becoming politically less so in a much more challenging economic environment.

All in all, any foreign firms or citizens doing business in China will need to assess not only business and political risk conditions inside China as they normally would and do, but also how they themselves might be affected in the light of new political risks arising between China and their own countries of origin. These are uncomfortable crosshairs in which they find themselves, and the FRL reminds them why that is so.

(George Magnus is a Research Associate at Oxford University’s China Centre and a Research Associate at SOAS, London.)