The Political Landscape After the 2025 Japan House of Councillors Election

On July 20 Japan held the 27th House of Councillors election. The ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Komeito secured a combined total of 47 seats. Including the 75 uncontested seats, the coalition’s total after the election stands at 122 seats. This marks a decrease of 19 seats compared to the pre-election composition and falls short of the 125-seat majority required in the House of Councillors. Picture source: Depositphotos.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 45

The Political Landscape After the 2025 Japan House of Councillors Election

By Shih-hui Li

On July 20 Japan held the 27th House of Councillors election. The ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Komeito secured a combined total of 47 seats — falling short of Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s pre-election target of 50 seats. Including the 75 uncontested seats, the coalition’s total after the election stands at 122 seats. This marks a decrease of 19 seats compared to the pre-election composition and falls short of the 125-seat majority required in the House of Councillors. Meanwhile, opposition parties made significant gains.

Severe defeat

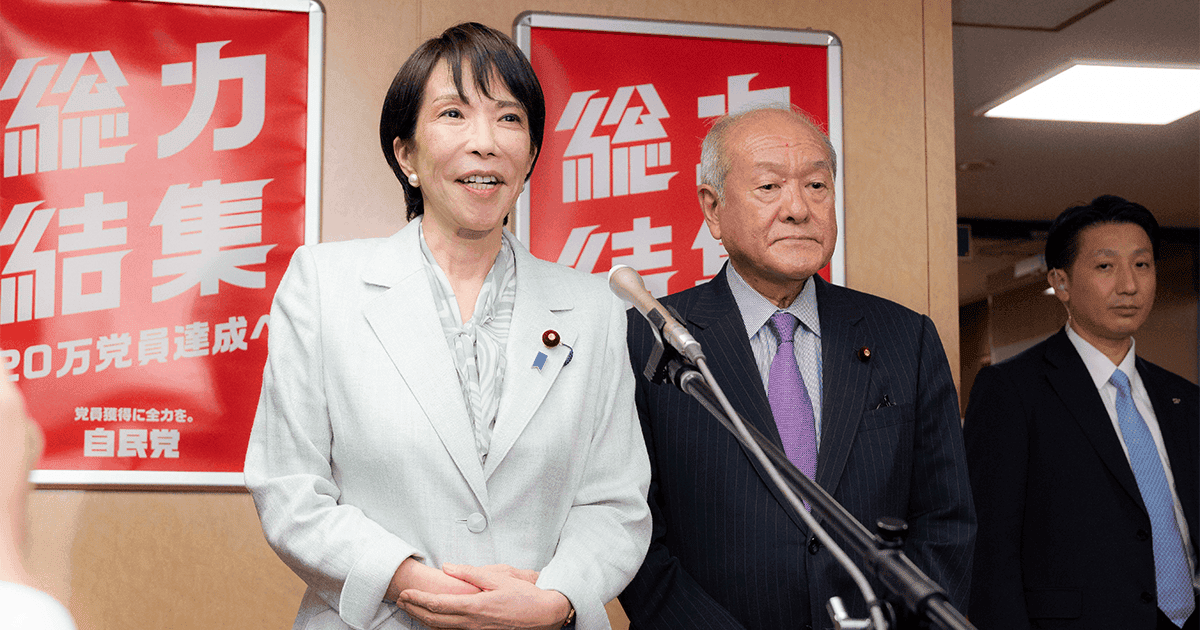

This election outcome represents a rare and severe defeat for the LDP. The loss has placed immense pressure on the current party head, Shigeru Ishiba. For example, Taro Aso publicly stated after the election that he does not support Ishiba remaining as prime minister, while Shinjiro Koizumi emphasized that the LDP president must uphold responsible governance and be accountable for the defeat. Moreover, Sanae Takaichi had already declared her intention, prior to the vote, to run in the next LDP presidential election. Members of the former Abe faction have also publicly called for Ishiba’s immediate resignation. Additionally, party organizations such as the Youth Division and local chapters in Ibaraki, Tochigi, and Kochi prefectures have submitted formal requests for Ishiba to step down.

Ishiba has long belonged to the LDP’s “peripheral faction,” remaining at odds with the dominant factions including the Abe, Aso, and Motegi groups. Although he enjoys the backing of the Kishida faction and several smaller groups, he has faced the fundamental challenge of a weak governing foundation from the outset. This electoral setback reflects not only the public’s accumulated dissatisfaction with the status quo — particularly regarding the economy — but also highlights the Ishiba administration’s lack of capacity to address pressing issues under mounting domestic and international pressure.

The implications of defeat

The outcome of the election has significant implications for Japan’s political dynamics, which can be summarized as follows:

First, the ruling coalition has lost its majority, undermining its governing foundation. Under the leadership of Shigeru Ishiba, the ruling bloc suffered a blow from public opinion, leading to weakened political legitimacy. Moving forward, the government will be required to seek support from opposition or neutral parties in order to pass legislation, approve budgets, and confirm key appointments. Notably, Komeito’s performance in this election hit a historical low, raising concerns about possible fractures within the ruling coalition.

Second, a shift among Japan’s conservative voters has eroded the LDP’s support base. Of the 32 single-member constituencies up for election, the LDP secured only 14 seats, losing 18. These districts have traditionally been conservative strongholds, particularly in agricultural prefectures. The LDP’s poor showing reveals not only a decline in local organizational mobilization and weakening grassroots connections but also a backlash from its conservative voter base.

Third, there is a growing trend of polarization within conservative politics. Parties such as Sanseito, with its “Japan First” nationalist rhetoric, and the Japan Conservative Party, known for its exclusionary stance, have gained both media attention and electoral support. The rise of these smaller conservative parties reflects voter disenchantment with the Ishiba-led LDP and indicates that conservative, exclusionary, and even populist ideologies are resonating with certain segments of the population, signaling a broader political polarization in Japan.

Assessments, local and foreign

Following the House of Councillors election, major Japanese media outlets expressed their views and positions through editorial commentaries.

Liberal media outlets critical of the LDP, such as the Asahi Shimbun and Mainichi Shimbun, sharply criticized the ruling LDP-Komeito coalition. They emphasized the emerging multi-party dynamics and expressed hope that opposition parties will take on a more prominent role. At the same time, they voiced concern over the rise of conservative ideology.

Conservative media outlets supportive of the LDP, including the Yomiuri Shimbun and Sankei Shimbun, focused their criticism on the Ishiba government. They urged the LDP to take seriously the loss of its conservative support base and called for Ishiba to take immediate responsibility by resigning.

The Nikkei Shimbun, which places strong emphasis on Japan-U.S. economic and trade negotiations, argued that the Ishiba administration is no longer capable of maintaining political stability. It called for the establishment of a more stable government to navigate the current turbulence in the global economic environment.

Western media coverage largely focused on three main themes. First, many highlighted the LDP’s worst defeat since its founding in 1955, noting the increased political uncertainty and challenges in governance (Times of India). Second, several outlets attributed the LDP’s loss to inflation and immigration issues, pointing to the rise of the Sanseito as a trend worth monitoring (Al Jazeera, The Guardian). Third, concerns were raised about how Japan’s political instability might negatively affect the yen’s exchange rate and the Japanese stock market (Reuters, Financial Times).

East Asian media coverage, on the other hand, concentrated on the implications for Japan’s foreign relations — particularly with South Korea and China. Outlets such as Dong-A Ilbo and Global Times interpreted the election result as a “red signal” indicating the possibility of improving bilateral relations, while also paying close attention to Japan’s growing rightward political shift.

On the other hand, within the LDP, the mainstream view in response to this electoral defeat is that it was not a failure of the party itself, but rather a failure of the Ishiba administration. This perspective is based on the observation that support for liberal or progressive parties did not increase; rather, voters with traditional conservative leanings shifted their support from Ishiba’s LDP to other right-leaning parties. These conservative voters diverge from the policy direction of the Ishiba government, which includes revising Japan-U.S. relations, allowing separate surnames for married couples, and phasing out nuclear energy.

As Ishiba’s LDP failed to represent these conservative interests, voters turned instead to parties such as Sanseito and the Japan Conservative Party, which espouse more traditional and nationalistic values. Thus, replacing Ishiba and reorienting the party’s policy platform away from liberal tendencies could be key to reversing the LDP’s declining support.

Consequently, for the post-election LDP, the central task is to regain the support of the conservative base represented by the former Abe faction. In the foreseeable future, factions such as the former Abe group, the Aso faction, and the former Motegi faction are likely to play a leading role. Internally, they are expected to push for a new party president, while externally seeking to build alliances with compatible opposition parties to form a new cabinet that reflects the ideological legacy of Shinzo Abe.

(Shih-Hui Li is Professor at the College of International Affairs, National Chengchi University and director of the Abe Shinzo Research Center.)