South Korea launched its Indo-Pacific Strategy, the so-called “Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region,” in December 2022. It is possible to say that the new Indo-Pacific strategy fully supports the U.S. strategy while maintaining good relations with China. Picture source: Depositphotos.

South Korea’s Indo-Pacific Strategy:

Ambitions and Reality

Prospects & Perspectives No. 11

By Niklas Swanström

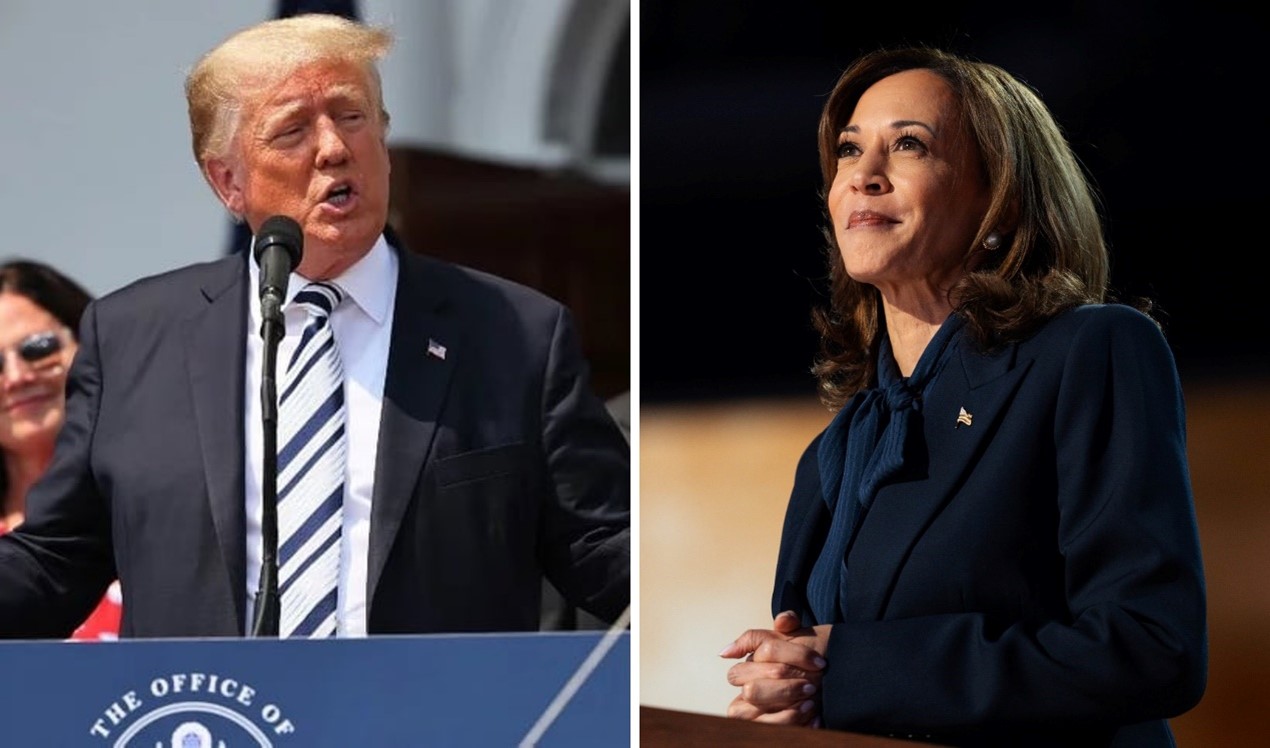

South Korea launched its Indo-Pacific Strategy, the so-called “Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region,” in December 2022. The strategy has rightly attracted widespread attention, not least because it resembles the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy and outlines a growing international engagement outside of the Korean Peninsula, but also because it attempts to balance the negative impact the shift could have on its relations with China.

A balancing act

With a solid normative language and position focused on international engagement with like-minded nations, President Yoon is simultaneously attempting to decrease South Korea’s reliance on China, which is creating tensions with Beijing, while not provoking unnecessary tensions with China that could have an impact on the economic and security engagements. For Taiwan, this is not necessarily a solid rock to rely on despite South Korea’s attempts to distance the strategy from China, and it is not by far the final word in the Yoon foreign policy strategy.

The U.S. and its allies notes the resemblances in the South Korean Indo-Pacific strategy to their own positions in the language of like-minded nations, freedom, norms and values, and an international order based on universal values. China, on the other hand, takes note of the fact that only once is China mentioned directly, and then with a positive ring when it is referenced to as a “key partner for achieving prosperity and peace in the Indo-Pacific region,” in contrast to the U.S. strategy that defines China as a “challenge.” It is not surprising that South Korea has left out all references to China that could be interpreted negatively and as a result China has been remarkably silent about the South Korean strategy, especially given the U.S.’s positive attitude toward the document. This might not only signal that both China and the U.S. are reluctant to provoke South Korea, but also that South Korea might be seeking to sit on the fence despite its strong rhetoric and that this strategy has been successful.

South Korea has been careful not to threaten or insult China unnecessarily, despite its implied relations with the U.S. and Japan. The refusal of President Yoon to meet with Former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi after her visit to Taiwan was one clear signal that, despite the intentions, South Korea is not ready to fully commit to a break with China. The language in the Indo-Pacific Strategy also signals to China that South Korea is a partner and is not seeking confrontation. This said, Yoon supports the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy through his own Indo-Pacific Strategy and his Alliance First Policy. This could result in full-fledged support for the U.S. and the ruled-based liberal order, but that is not necessarily the same as support of the U.S.’s conflict with China.

Economic considerations

The South Korean Indo-Pacific Strategy points out that the Indo-Pacific accounts for 78 percent of South Korea’s export but fails to mention that China is South Korea’s largest export destination by far, accounting for 27 percent of its exports. China, despite a drop during the pandemic, is crucial for South Korea’s economic development. This is even more accentuated regarding South Korea’s supply chains, rare earth minerals, and other critical nods in the South Korean economy. This is something President Yoon is acutely aware of and is seeing to change, among other things through the Indo-Pacific strategy, but it will take more than one president to change the economic fundaments to reverse this dependency. Still, the commitment to set out the first steps for a change is in the strategy, arguing for “a stable and resilient supply chain.”

The economic dependency on China will, despite good intentions and a strong message from the Yoon government, limit South Korea’s maneuver space. Regardless of the strong dislike for China in South Korea (80 percent of the population has an unfavorable view, according to PEW Research Center), the economic dependency severely limits South Korea’s ability to act independently. South Korea is acutely aware of the consequence of the Chinese sanctions as a result of the establishment of the THAAD air defence system in 2017, sanctions that impacted both South Korea’s economic performance as well as security situation. This is beyond doubt why the Indo-Pacific strategy puts a great deal of stress on diversification.

Additionally, South Korea suffers from a security challenge involving the military threat from North Korea. China can function as a conduit in inter-Korean relations or, even worse, act as a spoiler. The Yoon government has a more sober view of the expectations of talks with North Korea. Still, it is nevertheless dependent on China to maintain a position that defuses some of the tension, and prevents the Korean Peninsula from falling hostage to Great Power conflict. It is not unlikely that Beijing would be able to hold the intra-Korean relations hostage if South Korea decided to distance itself too far from China.

Still looking West

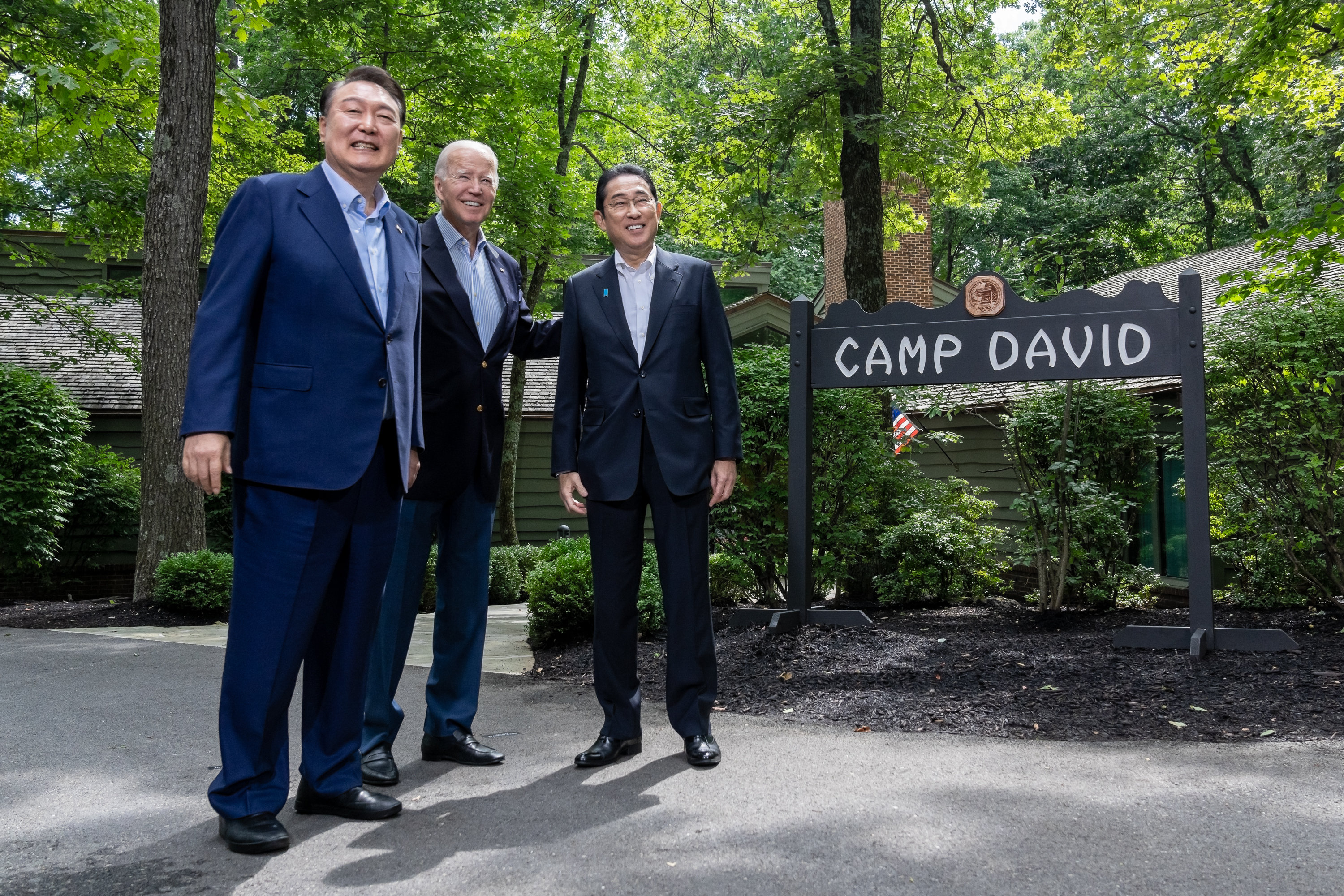

All this indicates a more lenient position towards China than the U.S. would prefer, but as noted before, this is not the whole story. The Yoon government is eager to consolidate its relations and security cooperation with the U.S. and improve relations with Japan, much due to China’s assertive behavior in the region and internationally. It even mentions Taiwan in the document — maybe for the first time in an official document — and the importance of peace and stability for regional security. Though direct support for Taiwan is unlikely, even if indirect support is implied through the Yoon government’s seemingly increased orientation towards democracies and liberal economies.

It remains to be seen if South Korea can afford to disengage China further and engage with the mini-laterals that have been emerging in the Indo-Pacific such as the QUAD and AUKUS, much to counter the influence of China. It seems complicated for South Korea to engage in what China would see as openly countering China’s “peaceful rise” with strengthened military cooperation with what Beijing would see as “anti-Chinese” forces. Still, it seems feasible to have South Korea cooperate in more economic and development schemes in the Indo-Pacific that are at least nominally open for Chinese engagement.

Will public opinion and President Yoon’s conviction to downgrade relations with China prevail, or will economic reality prevail? For the Yoon government, it could very well be that the economic costs are too high to further downgrade relations with China, even if a reduction of dependency in key sectors for national security are necessary, and underway. In that case, it will represent a fruition of China’s strategy of co-opting the South Korean economy. The South Korean Indo-Pacific-pacific strategy is applaudable and a step in the right direction, but expectations need to be more realistic in terms of what can be accomplished short-term as China has the South Korean economy in a chokehold. It is possible to say that the new Indo-Pacific strategy fully supports the U.S. strategy while maintaining good relations with China.

(Niklas Swanström is Director, Institute for Security and Development Policy; Head, Stockholm Korea Center.)