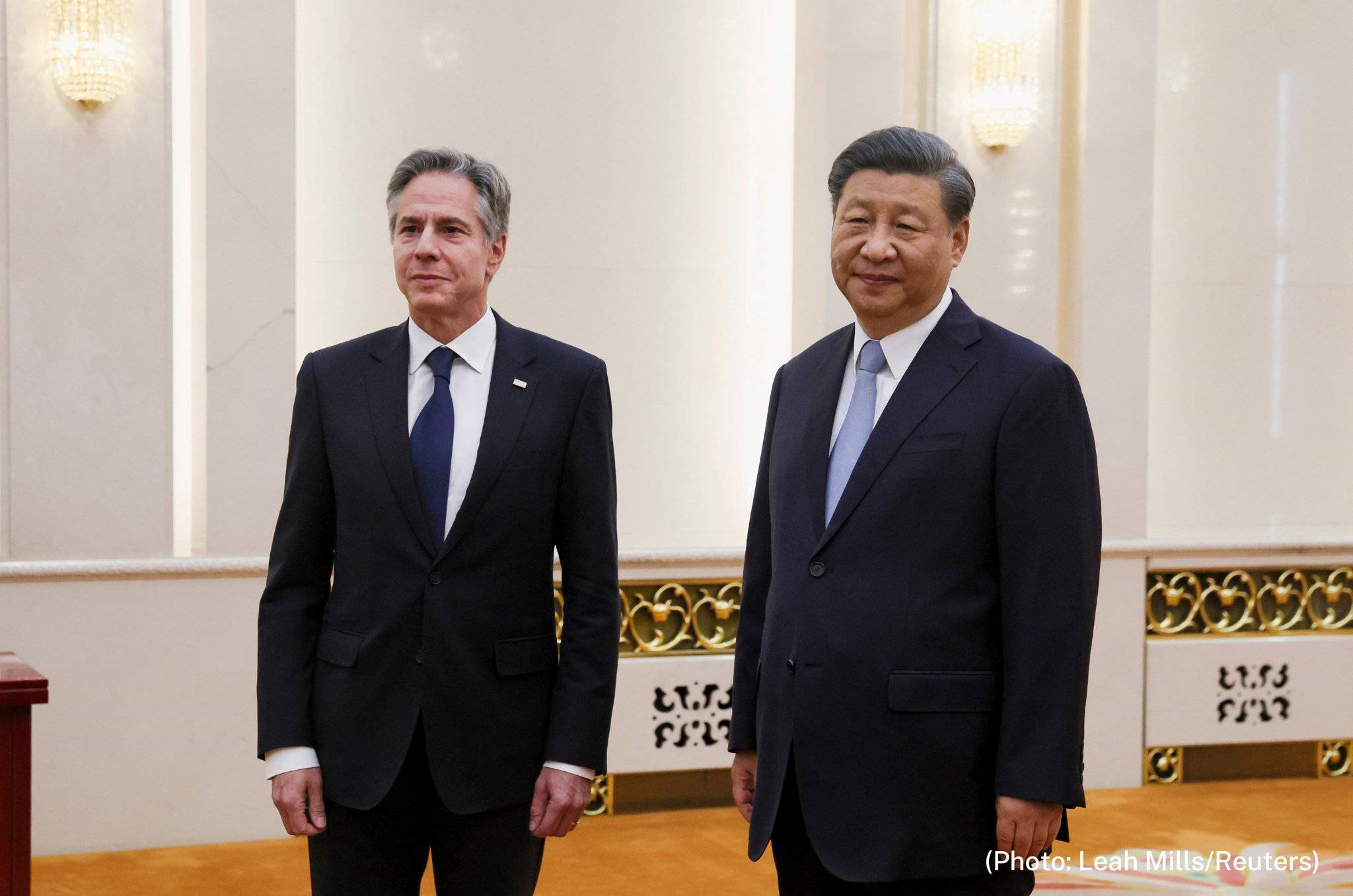

Blinken’s Beijing trip yielded nothing particularly substantive; the key request to improve military-to-military communications for crisis management and stability was not accepted, and all what was being agreed upon was more dialogue. This non-committal pledge also brings with it uncertainty about the modality at which such dialogue can be conducted. Picture source: Leah Mills/Reuters, June 20, 2023, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2360362870811179&set=pcb.2360363040811162.

A Firebreak Between China and the United States

Prospects & Perspectives No. 35

By Collin Koh

Yet one may also argue that the Chinese leaders were not prepared to be one-upped by their American counterparts, given the narrative that Blinken’s trip was aimed at demonstrating U.S. eagerness to alleviate tensions — which stood in stark contrast to the Chinese reluctance to do so, as highlighted by their refusal of Washington’s request for bilateral defense chiefs’ meeting on the sidelines of the SLD. Not only that, the last reported close air encounter above the South China Sea in late May, publicized by the U.S. military just mere days before the SLD, and a naval close encounter in the Taiwan Strait while the event was underway, gave the impression that Beijing was more interested in raising than lowering the temperature.

Divergence on “Commonsense Guardrails”

In any case, Blinken’s Beijing trip yielded nothing particularly substantive; the key request to improve military-to-military communications for crisis management and stability was not accepted, and all what was being agreed upon was more dialogue. This non-committal pledge also brings with it uncertainty about the modality at which such dialogue can be conducted. One should also bear in mind that the Americans and Chinese are basically apart on how they respectively perceive so-called “commonsense guardrails” that President Joe Biden coined during his first, virtual summit with Xi in November 2021.

To Washington, such guardrails essentially equate to confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) designed to promote crisis management and stability through maintaining “open lines of communication.” To Beijing, however, guardrails refer to refrain from undertaking actions or policies that are considered provocative, as broadly and ambiguously defined by the Chinese leadership as it deems fit for its interests. And crisis management mechanisms are not necessarily tools that the name implies; they often constitute tools of strategic leverage for China. Following then U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August last year, one of the first casualties of this political fallout was a set of military-to-military CSBMs that the Chinese suspended. That might have sounded counterintuitive, however, as this meant chucking these mechanisms into the drawer just when one needs them. But this is one of the techniques Beijing seems to have concluded would be useful in heaping pressure on Washington, playing on the latter’s desire to avert or reduce military risks.

So the euphoria over Blinken’s trip to Beijing, notwithstanding the outcome, looks set to be short-lived unless both China and the U.S. are willing to engage in meaningful political and military dialogue, and come to a real consensus on what exactly amounts to “guardrails” and devise parameters around them. At the same time, the realities on the ground — the regular interactions between Chinese and U.S. military air and naval forces in the region, especially in waters close to China — will remain dynamic, as both powers are unwilling to completely roll back on their military posturing that serves useful political signaling purposes.

Dynamic in fact to the point that would have seemed as if Washington was in fact the one holding out an olive branch of sorts. Reported freedom of navigation operations (FONOP) in the South China Sea (SCS), and transits in the Taiwan Strait are illustrative.

Posturing with Constraint or Self-restraint, or Both?

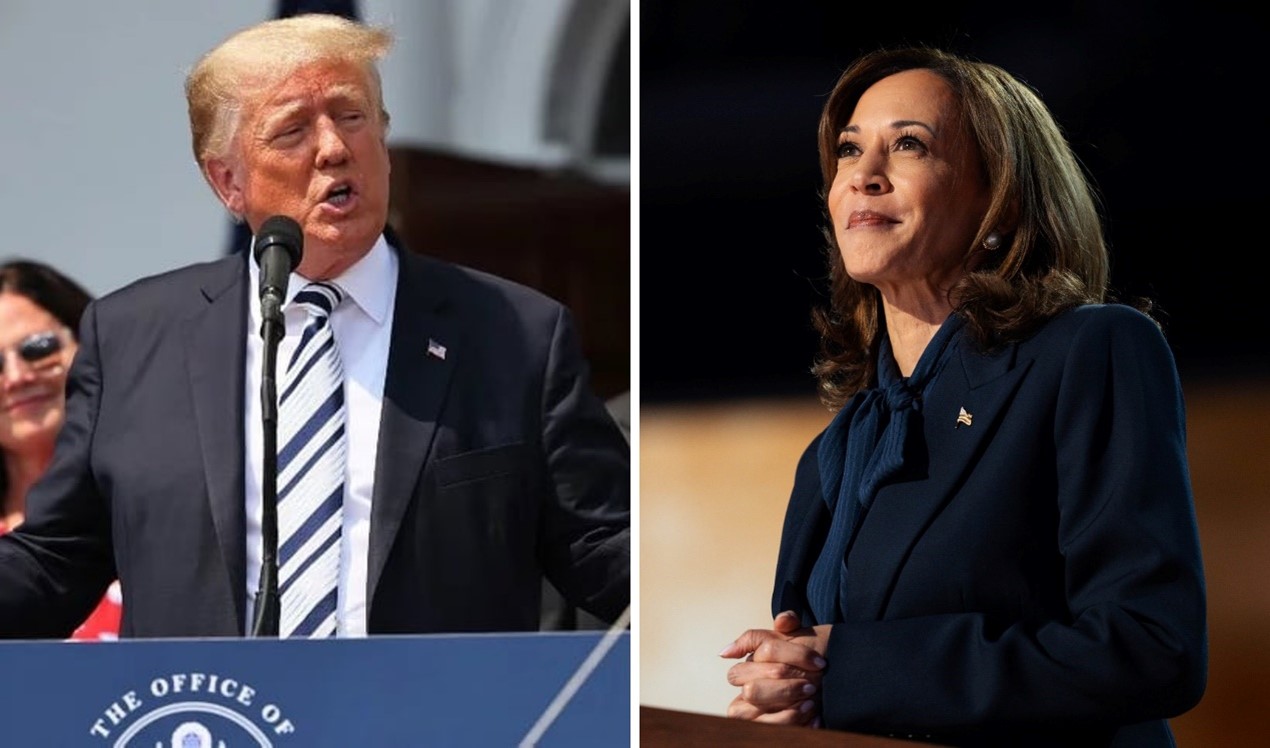

Reported FONOPs in the SCS exponentially increased under the then Donald Trump administration: four in 2017, five in 2018, eight in 2019, and finally 10 in 2020. Under the Biden administration, this figure dropped to five in 2021, and it hovered at the same number last year. So far, two had been conducted this year, with the last instance back in April. Compared to FONOPs in the SCS, reported Taiwan Strait transits were much more drastically bumped up: three in 2018, increasing three-fold to nine in 2019, then peaked out at 15 in 2020, before dropping to 12 in 2021. What appeared to be on an average one reported transit in the strait further dipped to 10 last year, one of which not conducted by surface forces but a P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft. This year’s tally held at five transits thus far, with the last early this month by American and Canadian warships that saw the close encounter with the Chinese forces, and of which two instances performed by P-8s.

This obvious decrease in reported FONOPs and Taiwan Strait transits could be attributed to the Biden administration’s desire to tamp down on tensions. It might well also be due to naval force capacity constraints. Unlike during Trump’s time, FONOPs under the current administration were typically conducted by a much less varied array of naval assets. From July 2021 to July 2022, all reported FONOPs in the SCS were conducted by just one distinct asset, the destroyer USS Benfold. And there is initial, preliminary sign that one warship would be tasked for both FONOPs in the SCS and transits through the Taiwan Strait. The destroyer USS Milius conducted its first FONOP in the SCS in late March this year, the second one in early April, before transiting the Taiwan Strait almost immediately after that.

Until the patterns become clearer, one thing at least is clear: there is a reduction in the tempo of these two sets of naval operations. Other forms of activities augment this, however. In recent years there has been an uptick in not only unilateral U.S. military presence operations in the SCS for instance, but also those performed alongside key allies. Just this month alone, three different sets of allied exercises were conducted in and around the SCS — Exercise KAAGAPAY between Japanese, Philippine and U.S. coastguards; Exercise NOBLE BUFFALO involving the navies of France, Japan and the U.S.; Exercise NOBLE RAVEN between Canadian, Japanese and U.S. navies; Exercise NOBLE TYPHOON between Canada, France, Japan and the U.S. navies.

The Chinese would of course take keen interest in these activities. Flush with newfound military capabilities thanks to sustained modernization of its air and naval forces in the recent decade, Beijing has routinely dispatched assets to keep close tabs on U.S. and allied military movements in what are considered China’s “near seas” such as the SCS. For the most part, the naval encounters have been professional and safe. Before the latest encounter in the Taiwan Strait, the last reported incident was back in 2018 between the Chinese and U.S. navies in the SCS. But aerial encounters appear to have been on an uptrend, with reported unsafe and unprofessional behavior exhibited by Chinese military aviators against U.S. and Australian forces.

Seeking a Firebreak

In other words, barring a total shift in their respective positions, the military posturing in the regional waters looks set to persist as both Beijing and Washington continue to utilize it for political signaling. And with this, the continued likelihood of close air and naval encounters, and the attendant risks of inadvertent clashes, between these rival forces.

Perhaps until the U.S. government lifts sanctions on Chinese Defense Minister Li Shangfu, the prospects for highest-level defense and military dialogue appear weak for the moment. Still, it bears mentioning that the Chinese have not yet renounced the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (MMCA) that was inked with the Americans in 1998, and under which the various CSBMs, especially the 2014 Rules of Behavior governing air and naval encounters (as well as its 2015 supplemental agreement), remain operative.

To be sure, this alone does not bring a wide measure of comfort given the current state of Sino-U.S. relations. As Beijing and Washington dig their heels deeper into their respective positions over bilateral differences, and continue to hold divergent views towards “guardrails” that can manage their tension, what is left is the prudence and restraint exercised by deployed military forces. They may well represent the ultimate firebreak in the absence of sustainable CSBMs, to prevent tensions from ballooning into an outright shooting match.

(Collin Koh is Research Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, based in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.)