The EU and Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific: Partners in Enhancing Multilateral Cooperation

The EU is aware of its vulnerabilities in the face of disruptions that might result from tensions across the Taiwan Strait. European policymakers are now focusing on developments in the Indo-Pacific, as they try to navigate regional strategic polarization. Picture source: 鍾廣政, October, 21, 2021, Radio Free Asia, https://www.rfa.org/cantonese/news/htm/tw-report-10212021063958.html.

The EU and Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific: Partners in Enhancing Multilateral Cooperation

Prospects & Perspectives No. 5

By Zsuzsa Anna Ferenczy

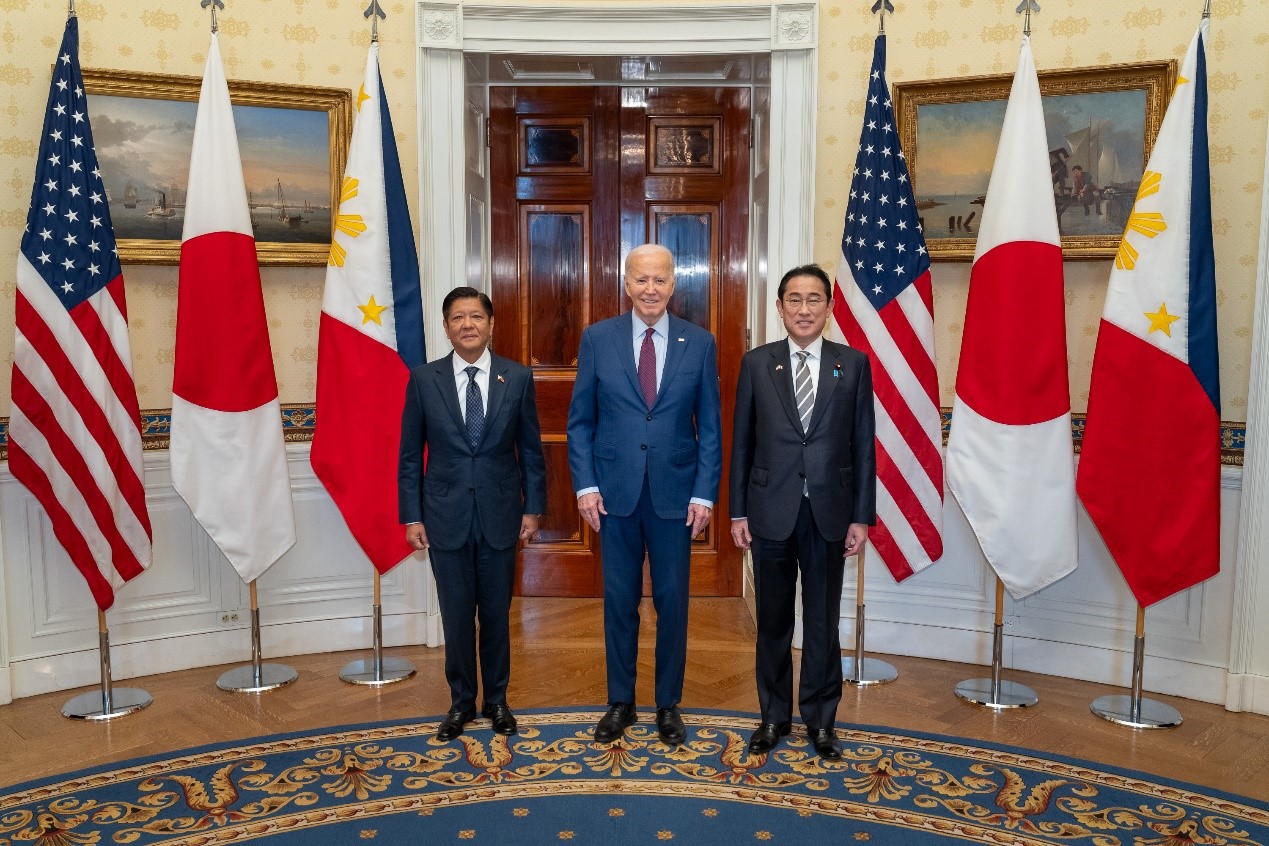

While not a “resident power” in the region, but having its own interests to protect, the European Union (EU) has been seeking to actively shape the Indo-Pacific debate. The EU is aware of its vulnerabilities in the face of disruptions that might result from tensions across the Taiwan Strait. Following decades of being busy dealing with issues at home, European policymakers are now focusing on developments in the Indo-Pacific, as they try to navigate regional strategic polarization.

Mistrust regarding China has recently intensified across Europe. Questions concerning Beijing’s reliability as a partner have further increased following Xi Jinping’s political support for Vladimir Putin in his brutal war against Ukraine. As Russia brought war back at the heart of Europe, democracies across the Indo-Pacific fear a possible crisis in the region brought on by China. As the EU seeks a stronger role that protects its own interests in the U.S.-China geostrategic rivalry, it must continue to effectively engage the region, in particular through the Global Gateway, its much-publicized strategy for infrastructure development. Taiwan must be part of this process.

The EU’s toughening stance on China

The Indo-Pacific, first conceptualized by Japan as early as 2007, has in recent years re-emerged as a response to the U.S.-China geostrategic rivalry, driven by the fears of regional states of being caught in the middle of the great power competition. Although most countries in the region were at first reluctant to adopt the term, the Indo-Pacific has entered their political discourse.

The EU has also embraced the concept guided by its own Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific released in 2021. The Global Gateway, its flagship infrastructure strategy adopted the same year, came in part as a response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with the ambition to promote the European model of trusted connectivity across the world, in line with the EU’s interests and values.

“Global Gateway is above all a geopolitical project, which seeks to position Europe in a competitive international marketplace. It is a critical tool because infrastructure investments are at the heart of today's geopolitics,” said Ursula von der Leyen at the first meeting of the Global Gateway Board in December 2022.

Although the EU shares the concerns of democracies in the Indo-Pacific regarding China’s growing clout, skepticism on the Global Gateway remains. Described by some as merely a “rebranding exercise” for drawing on resources already allocated by EU member states, the strategy has been criticized for lacking clarity. Others lamented the rather naïve view of the geo-economy driving the strategy, urging the EU to urgently address its long-term trade deficit with China, which has for years benefited Beijing’s global ambitions — and its BRI.

Notwithstanding the criticism, the Global Gateway reflects a hardening of views regarding China across the bloc and a readiness to tackle them on an EU-level. In order to address Chinese assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific, regional states have also started to elevate ongoing dialogues to a more strategic level featuring political, economic and security cooperation. The issues of focus of minilateral cooperation include strengthening maritime security through joint military exercises to increase interoperability and improve strategic coordination among like-minded countries that share common strategic objectives.

The rise of minilaterals in the Indo-Pacific

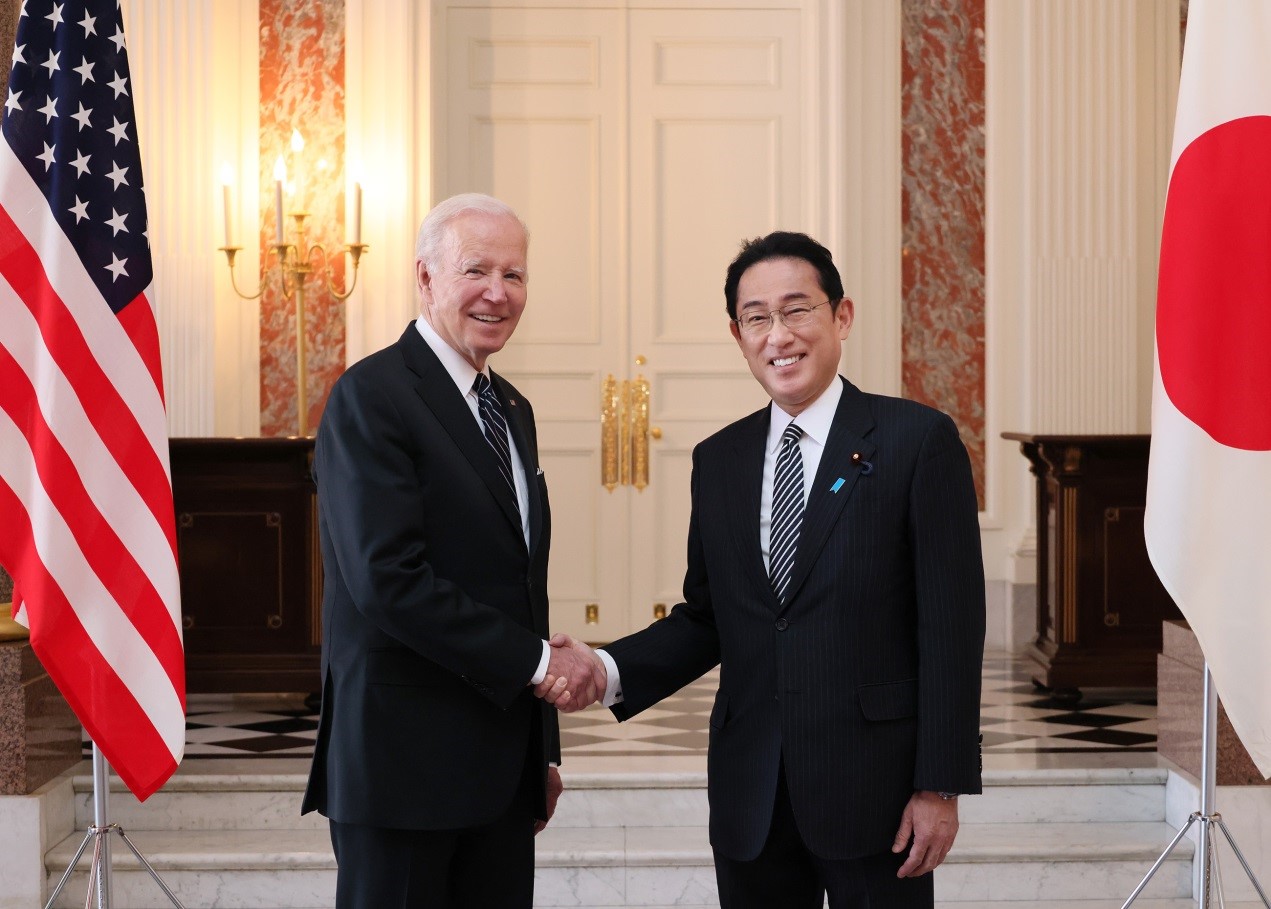

Bringing together the U.S., India, Japan and Australia, the Quadrilateral Dialogue, or Quad, is just one of the many minilateral dialogues that have shaped the region. Other trilateral dialogues, namely the U.S.-Australia-Japan, the India-Japan-Australia, or the India-Japan-U.S. trilaterals have supported establishing new institutional frameworks in a region challenged by a lack of consensus on international norms. In response to China antagonizing the region, with its Global Gateway the EU can contribute to embedding Taiwan into regional frameworks, and reshape global supply chains “based on trust and stability.”

India has made the Indo-Pacific central in its development trajectory, suggesting that its future will be shaped by the kind of role it manages to play in the region. Japan has actively promoted its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) Vision in efforts to strengthen its engagement with partners in the region. Finding it increasingly hard to insulate its commercial interests from regional tensions, Australia has embraced the concept as a means to manage its strategic environment, with elements that seek to balance China.

With shared worries by an assertive China, Delhi, Tokyo, and Canberra remain keen to both engage China and balance its rise with an inclusive approach. Under mounting pressure from Beijing, all three have started seeing Taiwan through the lens of security in the maritime and economic realms, showing readiness to engage Taiwan. The EU as a whole, but in particular some member states — namely the Czech Republic and Lithuania — has also shown willingness to integrate Taiwan into Brussels’ political discourse, supported by parliamentary diplomacy.

Finally, late 2022 Seoul unveiled its own Korean Indo-Pacific Strategy, a significant development as South Korea was one of the few regional partners yet to adopt the concept. In the Strategy, South Korean President Yoon called for “the building of a free, peaceful, and prosperous Indo-Pacific region through cooperation with major countries including ASEAN.” As an established regional entity, for ASEAN countries underscoring their centrality has been crucial in articulating their own ASEAN Outlook in the Indo-Pacific in 2019, marking a critical moment for the bloc’s embrace of the concept. The Quad has acknowledged ASEAN centrality, and so has the EU by upgrading its relationship with the bloc to a strategic partnership in 2020, reflective of Brussels’ adherence to multilateralism.

Minilateral deterrence

Following Russia’s war against Ukraine, the EU strengthened cooperation with like-minded partners. Albeit the war has re-centered Europe’s attention to its Eastern borders, it did not end its Indo-Pacific concerns. Rather, it further intensified Europeans’ will to protect their interests from authoritarian states. Taiwan remains at the heart of the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, but appreciating its relevance to Europe’s prosperity and security is going to require political will. Political will is going to be also vital to address the threat China poses to European values and interests.

With its Global Gateway, Brussels is at last getting serious about China. Building on the principled approach to connectivity at the heart of the 2018 EU strategy on connecting Europe and Asia, the EU should prioritize establishing a shared vision for an open and inclusive Indo-Pacific with its partners. But for a sustainable response, the EU must first ensure that member states don’t reverse its tougher stance on China. In this process, the EU must work harder to address the lack of reciprocity in EU-China ties and strengthen its defensive toolbox against Beijing’s economic coercion.

Second, in implementing the strategy, the EU must continue to work closely with regional partners who have strengthened cooperation within minilateral frameworks. Minilateral cooperation can help advance democracies’ shared interest in upholding multilateralism, an approach the EU has long supported. Going forward, the EU must embrace a comprehensive understanding of security and strengthen its cooperation with Taiwan in technology, cybersecurity, and economic and political resilience. No neighbor remains as exposed to China’s hostility as Taiwan. Cross-Strait issues are no longer bilateral, but multilateral issues. The EU must take a more pro-active role in embedding Taiwan deeper in regional frameworks, and emphasize deterrence to maintain regional peace.

(Zsuzsa Anna Ferenczy is Assistant Professor at National Dong Hwa University in Hualien, Taiwan, former political advisor at the European Parliament.)