Challenging Beijing’s Divide and Conquer Strategy: The Baltic States’ Exit from 16+1

The unity among the three Baltic states provides an important blueprint for other EU member states. While the bloc will continue to seek constructive and pragmatic exchanges with China, it should do so in a unified manner, in the spirit of its own fundamental values, including rule of law and human rights, and in line with the rules-based international order, specifically with regard to Taiwan.

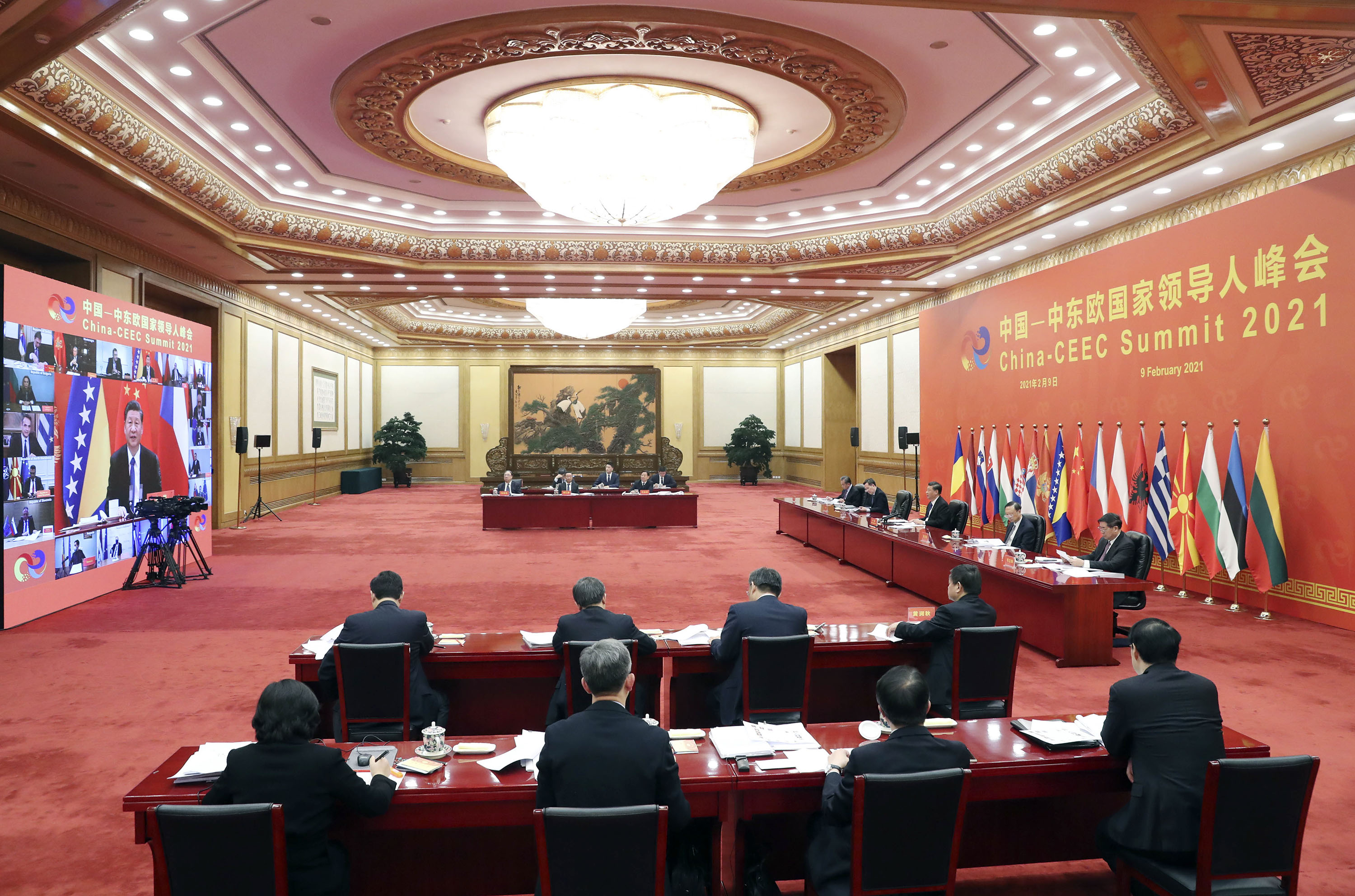

Picture source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, February 9, 2021, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/cebo//chn/zglc/t1852882.htm.

Challenging Beijing’s Divide and Conquer Strategy: The Baltic States’ Exit from 16+1

Prospects & Perspectives No. 52 September 13, 2022

By Marcin Jerzewski

On August 11, Riga and Tallinn delivered a major blow to Beijing’s diplomatic offensive in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) after the two Baltic states announced they were dropping out of the Beijing-backed Cooperation between China and CEE Countries framework. The initiative, established a decade ago as the so-called “16+1,” now counts 14 members after three countries announced their departures since last year. The weakening of this cooperation format, which has been widely criticized as China’s effort to “divide and conquer” Europe by undermining EU unity on Beijing, is indicative of a broader pattern of decline in China-CEE relations, which is occurring concurrently with the growing interest in many regional capitals to bolster ties with Taiwan.

Baltic Exceptionalism?

The Baltic states are unequivocally at the forefront in challenging the utility of the existing formats for China-CEE cooperation and calling for a more assertive and unified approach toward China across Europe. Lithuania became the first country to exit the initiative in May 2021. At the time, Lithuanian foreign minister Gabrielius Landsbergis asserted, “From our perspective, it is high time for the EU to move from a dividing 16+1 format to a more uniting and therefore much more efficient 27+1.” Consequently, the recent announcement by Latvia and Estonia that they, too, would leave the framework, can be understood as a sign of Riga’s and Tallinn’s solidarity with Vilnius, and the Baltic capitals’ support for the 27+1 cooperation with Beijing which Lithuania is strongly advocating.

The policy coordination between the Baltic capitals is not built exclusively on normative considerations about solidarity or intangible notions of “brotherhood,” but rather, the shared growing concerns about China’s influence in the region. Security considerations, amplified by Moscow’s and Beijing’s declarations of a “no-limits partnership,” should also be viewed as a factor behind the growing skepticism toward China among the Baltic states. The Soviet Union occupied these three EU member states until the early 1990s, and their publics continue to view Russia’s belligerence in the region as an existential threat. Thus, the growing confluence of strategic interests between Russia and China, and public declarations of mutual support, carry a lot of weight, undermining prospects for positive engagement with Beijing.

These security concerns are not newfound, as evidenced by the strong language about threats originating from China present in the three countries’ intelligence reports. For example, the 2020 National Threat Assessment published by the Lithuanian State Security Department highlighted that China’s pursuit of technological advantage through predatory investment schemes increases the vulnerability of states such as Lithuania through the loss of control over their critical infrastructure. This assessment is strongly related to the halted Chinese investment projects in Lithuanian, most notably a deep-water port construction in Lithuania’s Klaipėda. If successful, the project would likely have become a flagship initiative under the 16+1 framework, which defines cooperation in the fields of infrastructure, transportation and logistics as one of its priorities. Yet, the Chinese project in Klaipėda never took off, with Lithuanian President Gitanas Nausėda declaring it problematic due to the “national security aspect.”

In Latvia and Estonia, intelligence agencies have focused primarily on threats originating from China in the information space. Yet, the Latvian State Security Services also highlights that due to its “high innovation potential,” the country remains vulnerable to Beijing’s technological espionage, emphasizing the potential negative security externalities of Chinese investment. Riga’s and Tallinn’s decision to manifest a common Baltic direction in foreign policy development, expressed by their decision to follow Vilnius’ example in exiting the 16+1 framework, can thus be easily understood in light of these shared security considerations.

Three Seas Initiative as a New Regional Framework

The departure of the three Baltic states from the 16+1 cooperation framework does not put an end to regional investment and development cooperation. One mechanism that merits further consideration in this context is the Three Seas Initiative (3SI). 3SI involves 12 CEE countries, whose boundaries are delineated by the Adriatic, Baltic, and Black Seas. Established in 2015, this grouping takes a more tangible form through its annual summit, business forum, and investment fund dedicated to buttressing infrastructural projects in the sectors of energy, transport, and digital technologies.

The Baltic States actively participate in the 3SI forum, with Riga hosting the 2022 3SI summit and business forum and Tallinn, Estonia scheduled to organize the initiative’s digital summit later this year. During the Riga Summit, Estonian President Alar Karis said, “The Three Seas Investment Fund continues to be our biggest success and our most practical tool,” and, alluding to the normative underpinnings of the forum as a platform for economic cooperation between democracies, asserted that the fund constitutes a key tool for preventing authoritarian states from getting excessive influence over international infrastructure investments.

Importantly, the debate about links between 3SI and the Free and Open Indo-Pacific is already taking place, with Japan and Taiwan named among potential partner countries of 3SI in Asia. In an interview with the Taipei-based Central News Agency, the then-acting director of the Polish Office in Taipei, Bartosz Ryś, suggested that Taiwan could participate in 3SI and the 3SI Investment Fund to strengthen its cooperation with CEE countries, underscoring the normative underpinnings of the format which welcomed outreach to “like-minded partners” outside the region. In the case of Japan, Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa delivered a video address to the participants of the 2022 3SI summit, emphasizing that Japan remained committed to working with the members of 3SI “to enhance their resilience and prosperity.”

The juxtaposition between the three Baltic states’ departure from Beijing-backed 16+1 initiative and 3SI embraced by Washington also illustrates the importance of the U.S. factor in shaping the foreign policies of Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius. The Baltic States maintain strong and positive political, economic, and security relations with the United States. Notably, Latvia’s and Estonia’s decision to exit 16+1 came shortly after Lloyd Austin’s travel to Riga, which marked the first visit by a U.S. defense chief to Latvia since 1995. Austin’s trip is representative of Washington’s growing interest in the Baltic region and the security considerations therein. Amid the growing imminence of the Russian threat, Latvia also seeks closer cooperation with the U.S. to bolster its defenses, both through access to training as well as revamping its military hardware.

Concurrently, the U.S. has also demonstrated its tangible support for 3SI as a preferred format for regional economic cooperation. In 2020, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced the intent to invest up to US$1 billion in the Three Seas Fund, with the pledge winning bipartisan approval in Congress. As 3SI bolsters collective cooperation within the CEE and undermines China’s “divide and conquer” strategy in the region, the support for 3SI is clearly aligned with US’ geopolitical objectives in the eastern part of Europe.

Toward 27+1? Toward Taiwan?

The growing concern about the national security implications of Chinese investments in CEE should also be viewed closely in Taipei, as they provide a window of opportunity for Taiwan to deepen its ties with the region. Lithuania has positioned itself as a leader in Taiwan-CEE ties, and its steps are watched with great scrutiny in other Baltic capitals. In an interview with the Estonian Public Broadcaster EER published on the eve of Tallinn’s departure from 16+1, legislator Jüri Jaanson of the ruling Reform Party advocated for the opening of a Taiwanese representative office in his capital. Jaanson argued that Lithuania’s decision to allow such an office to open in Vilnius has provided Estonia with important insights into the Chinese modus operandi, while Lithuania’s broader outreach to Taiwan brought the Baltic nation tangible economic benefits.

These dynamics are important not only for Taiwan and its quest to expand its international space, but also for the EU amid the calls to adopt a more effective 27+1 approach and communication with Beijing. The unity among the three Baltic states provides an important blueprint for other EU member states. While the bloc will continue to seek constructive and pragmatic exchanges with China, it should do so in a unified manner, in the spirit of its own fundamental values, including rule of law and human rights, and in line with the rules-based international order.

Specifically with regard to Taiwan, the Baltic states demonstrate that while the EU’s “One China” policy will remain in place, there is ample space for developing mutually beneficial relations with the island, particularly in the areas of economic and people-to-people exchanges—despite China’s intimidation. Governments in Prague and Bucharest, which have also expressed interest in deepening ties with Taiwan, are most likely to be the next in following the suit of the Baltic Three and exiting the Beijing-backed 14+1 cooperation format and pushing Brussels and other European capitals towards a 27+1 approach. Yet, despite these positive developments in CEE, the fragmentation of the European approach to China, which can be attributed to conflicting economic interests of the 27 member states and juxtaposed with greater cohesion in responding to authoritarian threats from Russia, remains one of the greatest challenges to the European Common Foreign and Security Policy.

(Marcin Jerzewski is the Head of Taiwan Office at the European Values Center for Security Policy.)