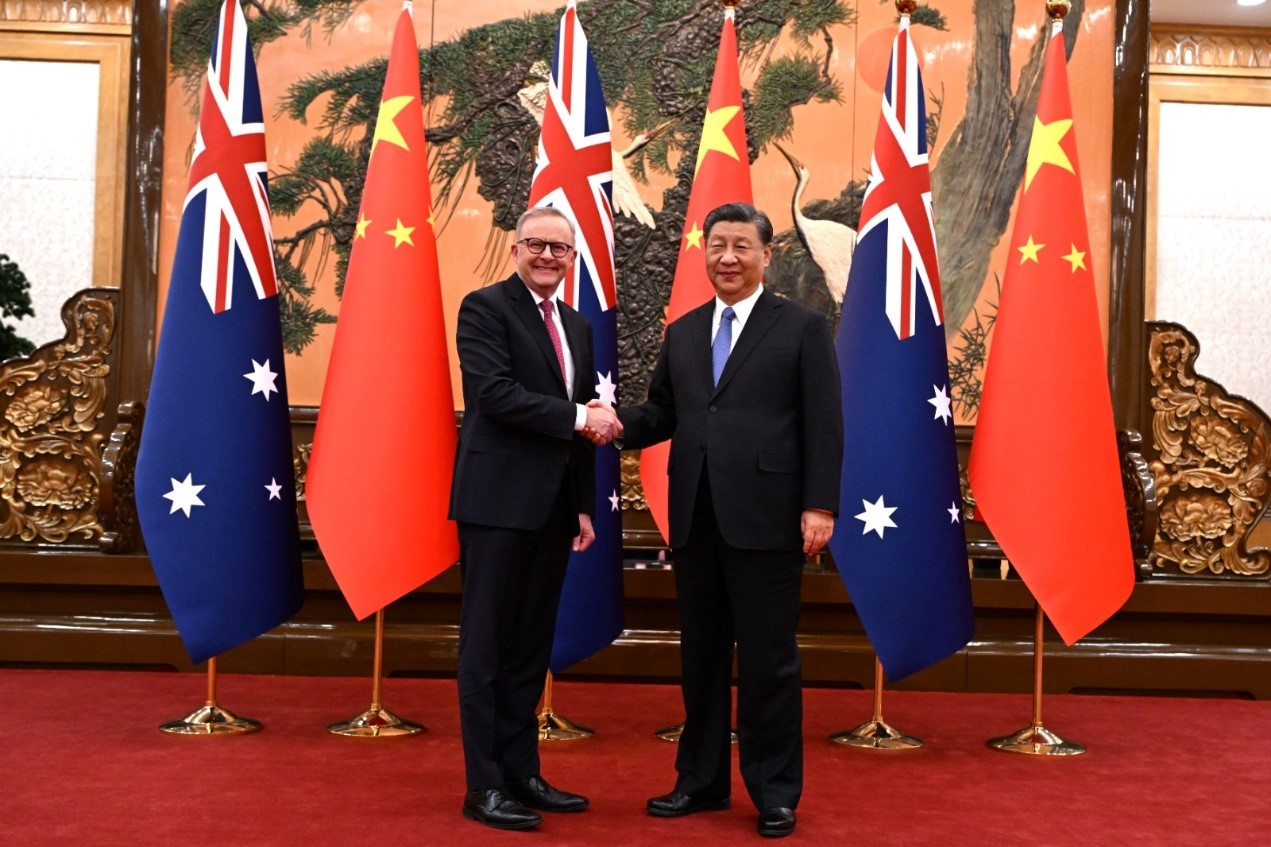

It may take some time for Australian leaders to come to the realization that “stabilizing relations” with a country that relies on escalation, intimidation and tactical surprise is a difficult if not impossible task. Rather, the more one concedes to Beijing, the more it demands. Picture source: Malcolm Roberts, November 7, 2023, X, https://twitter.com/MRobertsQLD/status/1721709063954993346/photo/1.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 6

Australia’s Response to Taiwan’s Election

By Lavina Lee

As in many countries around the world, Australian interest in the outcome of Taiwan’s nail-biting election on January 13 was unprecedented. Under the specter of increasing Chinese threats, the historic third-straight presidential term for the incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) candidate Lai Ching-te sent the clear message to the world that Taiwanese voters would not be intimidated.

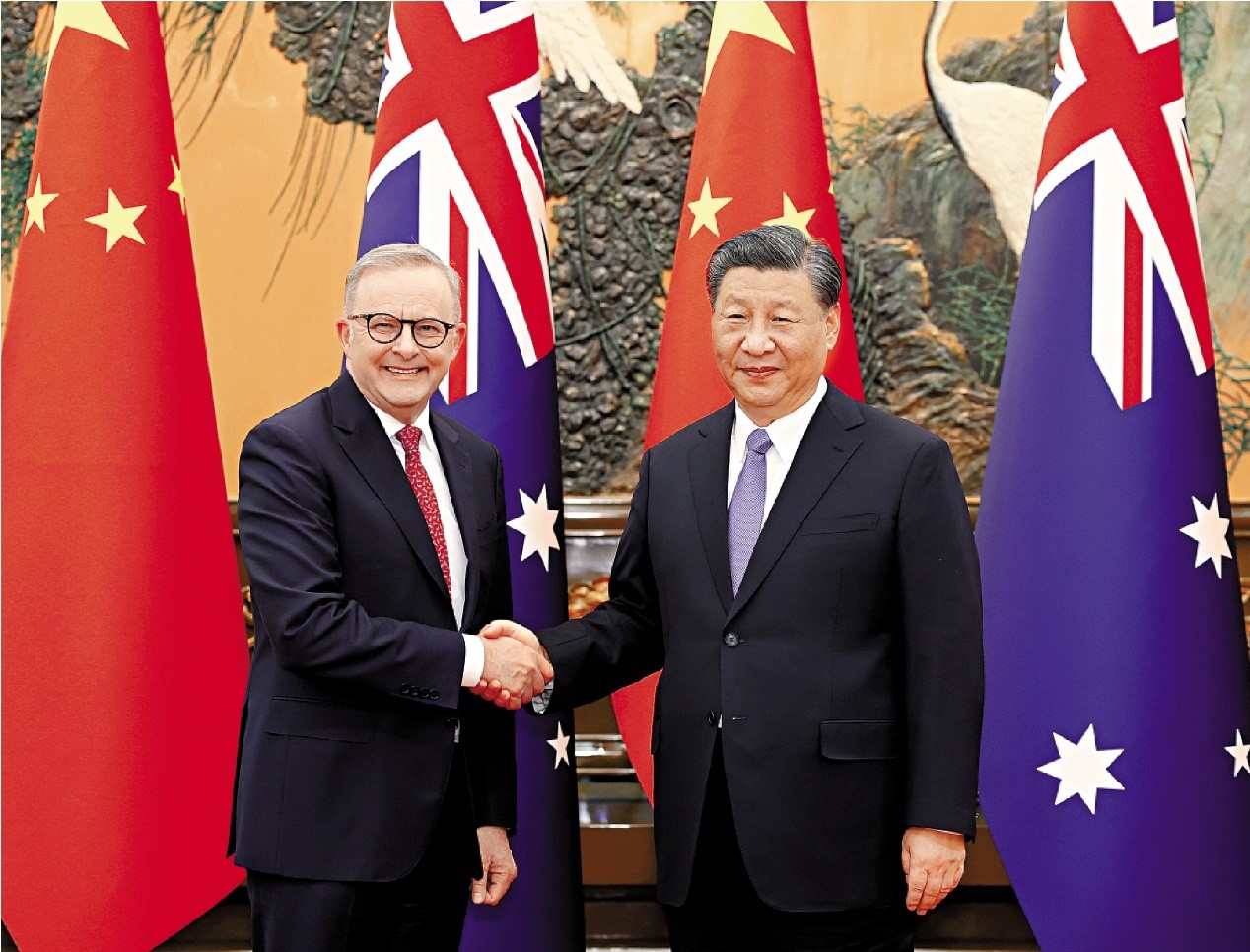

The timing of the election has been awkward for the Australian government. Since coming into office in March 2022, the new Labor government has been working assiduously to resume diplomatic dialogue with Beijing with the latter refusing to take calls from Ministerial counterparts since April 2020. It was only on November 6, 2023, that Prime Minister Albanese shook hands with Xi Jinping in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, the first visit to China by an Australian prime minister since Malcolm Turnbull in 2016. Taiwan’s election is an early test of what Canberra is willing to do to improve its relationship with China.

Canberra’s cautious response

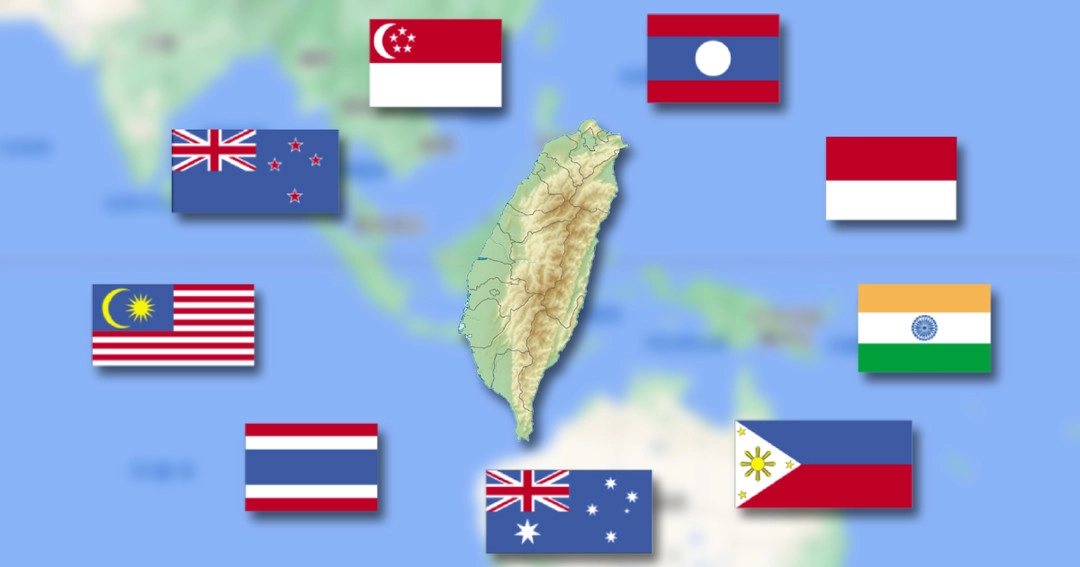

Importantly for Taiwan, Australia’s official statement congratulated President-elect Lai on his victory and the “people of Taiwan on the peaceful exercise of their democratic rights.” It went on to praise “the maturity and strength of Taiwan’s democracy” and confirm the intent to continue to advance “our important trade and investment relationship… and our deep and longstanding educational, scientific, cultural and people-to-people ties”. Prior to the election, Prime Minister Albanese called on all countries to respect the outcome of democratic elections, including in Taiwan. In taking this stance, Australia joined with other democracies — the United States, the UK, Japan and the Philippines for example — in affirming the Taiwanese people’s right to hold democratic elections and make free choice about their future.

Compared to others, however, Australia’s statement was cautious and modest. It avoided any pre-emptive support for Taiwan in anticipation of a coercive Chinese response to the return of the DPP to power. Less reticent were the U.S., which confirmed its commitment to “maintaining cross-Strait peace and stability,” while the UK’s Foreign Secretary David Cameron called on both sides (read China) to “renew efforts to resolve differences peacefully… without the threat or use of force or coercion.” Others were also more effusive about the depth of their relations with Taiwan. The Philippines spoke of furthering the two countries “close collaboration” whilst Japan went the furthest in describing Taiwan as “an extremely crucial partner and important friend, with which it shares fundamental values” and stated the intent to deepen cooperation and exchanges further. Even the careful Singapore described the relationship as a “close and longstanding friendship” and expressed support for the “peaceful development of cross-strait relations.”

This invites speculation as to whether Australia’s relatively muted response was influenced by the menacing warning issued by the Chinese Ambassador to Australia on election eve that “[I]f Australia is tied to the chariot of Taiwan separatist forces, the Australian people would be pushed over the edge of an abyss.” He made clear that Canberra’s approach to the new Taiwanese government could “undoubtedly undermine” Australia’s relations with China. On January 17, in a two-hour post-election press conference in Canberra, Ambassador Xiao Qian said that China was willing to be flexible in many areas in the relationship with Australia, including to resolve trade disputes, but on the question of Taiwan, “there is no room at all for us to show flexibility or to make compromise.”

Canberra has remained silent in the face of these veiled threats and made no attempt to call in Xiao for a diplomatic censure. In doing so it reveals that in its efforts to tread lightly with China — and achieve what it describes as a “stabilization” of the bilateral relationship — it is increasingly allowing Beijing to dictate the terms of Australia’s relationship with Taiwan. Australia’s One China policy “acknowledges” the PRC’s claim to Taiwan and calls on Beijing and Taipei to resolve their dispute peacefully. Nothing in this policy impedes Australia from exploring deeper trade, investment and diplomatic relations with Taiwan in areas of mutual interest. How far an Australian government decides to push forward the bilateral relationship is a matter of temperament and a reflection of national priorities.

Australia pays a high price for stabilizing the China relationship

The previous Liberal government was prepared to take great risks to push back against Beijing to defend Australia’s democratic institutions and sovereign decision-making, and to take overtly confrontational positions to defend liberal international norms and institutions. China’s post-2020 diplomatic freeze on the bilateral relationship and accompanying economic coercion of Australia was direct punishment for standing up to China too successfully and encouraging others to do the same. This includes calling on China to abide by the 2016 South China Sea arbitration ruling, enacting foreign interference legislation, banning Huawei from 5G networks, and tightening foreign investment rules on national security grounds.

The current Albanese government has sought to distance itself from this approach as one that is unduly provocative in tone. It maintains that “stabilization” of the relationship with China will not come at the expense of Australia’s national interest. Accordingly, Albanese often states that Australia will “cooperate with China where we can, disagree where we must, and engage in our national interest.”

These ostensibly bold words mask the high price Australia has been prepared to pay to clear a path for Albanese’s November 2023 meeting with Xi. First, there is Australia’s August 2023 decision to drop its case against China for trade duties it imposed on Australian barley after a WTO panel had reportedly handed down a final report in Australia’s favour. Canberra was happy to allow Beijing to resume importation of Australian barley without restitution to Australian farmers, any acknowledgment of fault, and to forsake the opportunity to defend the rules of the WTO and allow China to escape legal rebuke for engaging in economic coercion. Second, leading a trade delegation of almost 200 Australian business leaders to the China International Import Expo sent the clear signal that Canberra was willing to forgive China’s coercion and to raise expectations among domestic traders of a coming boom in bilateral trade. Such behavior contradicts efforts among Australia’s allies and partners to “de-risk” and reduce their economic dependency on the Chinese market for critical goods and technologies.

Third, there has been a discernible dampening of the current government’s appetite to confront of China in defense of Australian interests. Australian leaders no longer refer to “economic coercion” but to “trade impediments.” In November 2023, a Chinese warship used sonar near an Australian frigate upholding the UN sanctions regime against North Korea in international waters of the East China Sea. Four Australian navy divers were injured by the sonar blasts. However, Albanese chose to avoid raising the issue directly with Xi at the San Francisco APEC meeting, despite the seriousness of the issue and was forced to issue a firm public statement afterwards under political pressure.

China in turn has not given away anything of significance, other than to remove most of the coercive trade sanctions that it should not have applied in the first place, and to release an Australian journalist — Cheng Lei — who had been spuriously imprisoned for more than three years for breaking an embargo on a Chinese government briefing by a few minutes. One further Australian citizen continues to languish in a Chinese prison, Yang Hengjun, a democracy activist and writer detained in China since 2019 and charged with espionage last year. In recent days, Chinese Ambassador Xiao made the audacious claim that the use of sonar was not by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) but from a likely Japanese source, essentially accusing Australia of confecting the incident. None of this suggests that China is seeking a new era of friendlier relations with Australia.

The upshot for Australia-Taiwan relations

It may take some time for Australian leaders to come to the realization that “stabilizing relations” with a country that relies on escalation, intimidation and tactical surprise is a difficult if not impossible task. Rather, the more one concedes to Beijing, the more it demands. In the meantime, Australia is choosing the path of timidity and has little appetite to lead on widening Taiwan’s international space to support the continuation of its de facto statehood. The implications of this are that Taiwan cannot expect Canberra’s support for its application to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), initiatives to deepen bilateral trade, or expansion of engagement and between governmental counterparts. Under present leadership Australia cannot be relied upon to be a champion for Taiwan.

(Dr. Lavina Lee is Senior Lecturer, Department of Security Studies and Criminology, Macquarie University, Sydney.)